This feature examines the origins of women’s football in Bradford and considers the impact of the Football Association’s ban on women’s football in 1921 on the subsequent development of the game in the district. Case studies of the early Bradford experience provide an illustration of the prejudices about women’s football. Below an advert in the BCAFC programme, April 1921.

The ban on women’s football

The advances of women’s football in the last few years and the growth in its profile make it seem all the more incredible that between 1921-71 the Football Association enforced a ban on women’s football being staged on any of the grounds of its member clubs, whether Football League stadia or amateur pitches.

The ban in December, 1921 came just at the time when certain women’s sides – most notably Dick, Kerr Ladies – had demonstrated a capability to attract huge crowds. The best example of this had been on Boxing Day, 1920 when a reported crowd of 53,000 had attended Goodison Park (and a further 14,000 were locked out) for a game involving the Dick, Kerr team against St Helens Ladies that raised £3,115 for charities. The scale of the crowd is all the more remarkable for then having been the second largest ever recorded for any association game in England.

The Dick, Kerr team, comprising employees of the Dick, Kerr munitions factory in Preston had been formed in 1917 and during World War One had played games to raise money for soldiers’ charities. It was not unique and other teams were formed by female munitions workers. In 1917, fourteen women’s teams entered the new Munitionettes Cup competition which was probably the first to cater solely for women’s football.

After the war Dick, Kerr Ladies had continued to participate in exhibition games across the north of England, including Bradford, with the matches promoted to raise funds for charity – for example, for the benefit of injured ex-servicemen or hospital funds. The emergence in 1921 of the Manningham Mills Ladies team, followed shortly after by Hey’s Ladies, suggest that Dick, Kerr Ladies inspired the formation of other works-based teams. Of itself it was unique within British football that a works side should achieve such prominence.

(It should be highlighted that Dick, Kerr also organised a women’s hockey team around this time and the encouragement of sport in this way needs to be considered in the context of employer paternalism. Similarly, Manningham Mills and Hey’s Brewery fostered women’s cricket teams.)

The Dick, Kerr Ladies team was also relatively unique in so far as its games were exhibition matches – rather than league or cup games – against other women’s sides and in this regard it had more in common with such as the Corinthians who arranged ad hoc fixtures with men’s teams (both professional and amateur). At the time there was no national league or cup competition for women’s football and thus Dick, Kerr Ladies organised games by invitation. Presumably Dick, Kerr Ladies were similarly no different to the Corinthians in avoiding fixtures where costs could not be recovered.

Yet why could the Football Association have been so bothered about the rise of women’s football? Casting aside any aspersions about members of the FA’s leadership committees, my belief is that what prompted the ban on the women’s game was concern that the integrity of the (men’s) game might be undermined if football became known equally for showground spectacle (by women) rather than just competitive contest (by men). The fact that outside commercial interests stood to benefit was another factor in this. The Football Association considered itself responsible for upholding the self-respect and standards of the game and it was a legitimate worry that the sport could be de-valued in some way. Take for example the popular opposition that has arisen in the modern era when American promoters have suggested changes to the ‘rules of soccer’ for the principal purpose of making it more of a spectacle. That is not to condone the FA’s ban as opposed to try and understand how it could have come about.

The ostensible reason for the Football Association ban of 5th December, 1921 was that although games were advertised as charity fund-raising, it was claimed (following specific incidents in Plymouth and Dundee) that not all the proceeds were applied for that purpose. The inference was that individuals could be making private gain and the FA was known to be sensitive to the spectre of financial irregularity in the game, irrespective of male or female participants.

Discomfort may have also been caused by the fact that the Dick, Kerr side was openly linked to the Preston firm of the same name (later known as English Electric) which would have derived commercial benefit from the publicity. Take for example that the Dick, Kerr Ladies side was credited with pioneering floodlit football and in December, 1920 staged a game under floodlights at Deepdale, Preston in front of a 10,000 crowd. The fact that the Dick, Kerr Ladies enjoyed the advantage of the parent firm possessing core skills in electrical engineering raised the suspicion of gains accruing from linkage with a sponsor. The Football Association thus faced a potential threat that the game might become hijacked by outside commercial interests who were not financially accountable.

It seems likely that the Football Association perceived the phenomenon of women’s football as a material threat. There is a strong case that the ban arose because the FA was concerned that curiosity for, and the distraction of, women’s football might undermine the men’s game. A headline theme was the scale of public interest with attendances at games involving Dick, Kerr Ladies being typically in excess of those of third division clubs in the Football League. During the calendar year of 1921 the side played as many as 67 games with aggregate attendances of around 900,000 – an average of just over 13,000 which was impressive by second division standards.

However, that the Football Association justified its ban by claiming football was not suited to the physiology of women makes it difficult to avoid the accusation of misogyny. The fact that it came so soon after women had been given the vote in 1918 and the passing of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of 1919 (which had ended legal discrimination against women) implies a revanchist agenda on the part of the Football Association. From today’s standards the decision is difficult to believe as well as indefensible.

Although a number of prominent male players expressed disapproval about the ban, the Football Association action in 1921 did not prompt political uproar or widespread opposition in the country at large. In other words, at the time it was not considered particularly controversial. How then can the action of the FA be explained? Examples of the early experience of women’s football in Bradford may offer some clues about the social and cultural perspectives that existed a hundred years ago.

The first women footballers in Bradford

The origins and history of women’s football in Bradford has received scant attention. In the limited coverage of the subject, even so-called (or rather, self-proclaimed) leading historians of sport and leisure have fallen into the trap of taking historic mention of women’s football matches at face value. For instance Pendleton, whose book Kick Off! (2018) specifically examines the early history of women’s involvement in sport in Bradford, fails to recognise that in the nineteenth century and for much of the twentieth, women’s football matches were treated as showground spectacles rather than serious competitive fixtures. Yet this distinction is crucial in understanding the evolution of women’s football in Great Britain and of how it was shaped by social prejudices.

Three separate accounts of women’s football matches in the Bradford district confirm the prejudice and misogyny that existed in relation to female participation, illustrating how games were staged for the amusement and titillation of predominantly male spectators, principally as shows of farce and mockery. Women’s football had novelty value, akin almost to a freak show or circus. The reports of games – all of which were association football – at Windhill, Shipley in 1881, Valley Parade in 1895 and Park Avenue in 1917 are consistent in highlighting that those attending had not done so for the purpose of watching a serious game.

One hundred years ago, at a national level few of those involved with the men’s game took women’s football seriously. In the Victorian era women’s football had been associated with exhibitionism and this continued to pervade attitudes. That few people could imagine otherwise was confirmation of the prejudice and social opinions that were then commonplace. An example of this is the following ballad that was published in the Yorkshire Sports (Bradford) in 1901:

Locally, players and officials from Bradford City AFC can be credited with having given assistance to women’s football with individuals involved with the game at Park Avenue in 1917. Similar goodwill was extended in 1921 towards the newly formed Hey’s Ladies. The support could equally be interpreted that women’s football was not considered a threat to the Valley Parade club, let alone to the men’s game.

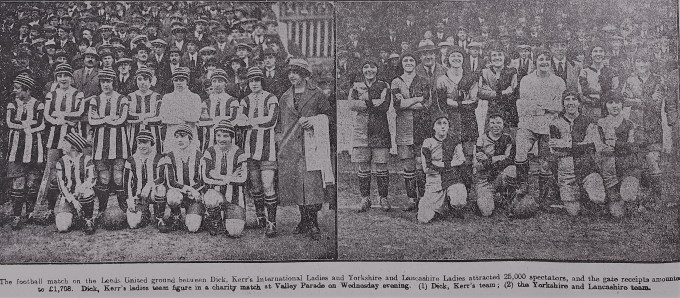

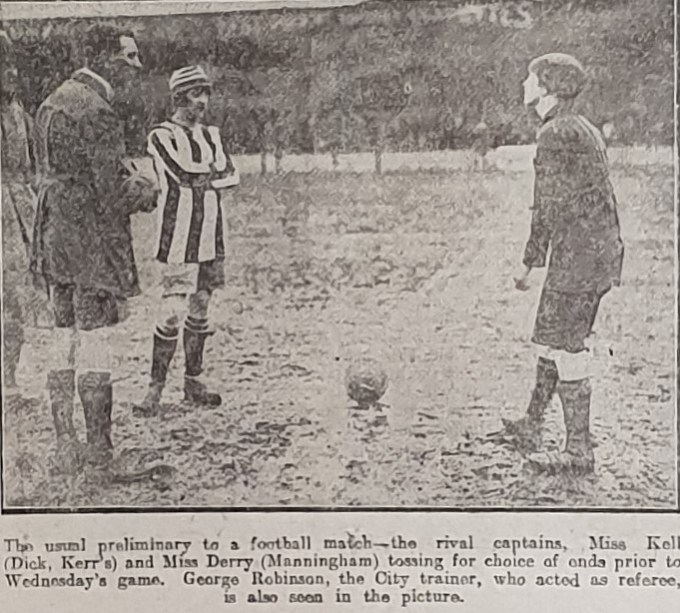

In Bradford two new sides had emerged. They were not the pioneers in West Yorkshire however; the Huddersfield Atalanta club had been formed in November, 1920 (non-works related, comprising middle class membership). First came the Manningham Mills Ladies’ side in March, 1921 (also known as Lister Ladies) whose members came from the mill’s hockey team and whom Dick, Kerr Ladies defeated 6-0 at Valley Parade in front of a reported 14,000 on 13 April (pictured below).

The day after, Dick, Kerr Ladies repeated the victory over Lister’s at Millmoor, Rotherham by 7-0 with a crowd of over ten thousand. In August, 1921 Hey’s Ladies (formed in April that year – inspired perhaps by Listers – and another works side based in Manningham, being that of the eponymous brewery) played Dick, Kerr Ladies in Leeds but were defeated 0-9 and a week later Dick, Kerr’s again defeated Lister’s Ladies, this time by eleven clear goals. In October, 1921 Hey’s Ladies met Dick, Kerr Ladies at Valley Parade and the score was more respectable, a defeat by only 1-4. (The crowd of that game has been variously reported as 4,070 and 10,000 and stated attendances may have been exaggerated for effect.)

Photo from Leeds Mercury 14th April, 1921: DKL (stripes) v Lister’s at Valley Parade

What is distinct about the sponsorship by Hey’s Brewery is that, as a consumer-facing business, the promotion of a women’s football team offered considerable commercial opportunity through brand exposure and awareness. By contrast, whilst Dick, Kerr’s (or Lister’s of Manningham Mills) would have enhanced their company profiles and raised employee identity / morale through sponsorship of women’s football, the direct commercial benefits were less obvious. The heritage of Dick, Kerr for example was railway and tramway equipment and whilst football would have enhanced the profile of the firm, the link with selling locomotives could have been no more than indirect. Likewise, whilst the promotion of floodlit football could be portrayed as an advert for the firm’s electrical engineering competences it did not represent a form of direct marketing.

Like Dick, Kerr’s who were understood to have raised as much as £70,000, the games of Hey’s Ladies were advertised for the purpose of generating funds for charity. Therein was a similarity with the local origins of men’s sport because charity fundraising had been a driving factor behind the impetus for athletic sporting events in Bradford in the 1860s. By the 1920s, such had been the track record of football that most people in Bradford would have been cynical at the suggestion that the sport could be a bastion of charitable support. As I have written in my books, the record of men’s football in Bradford at charity fundraising had been poor but this could have made people responsive to the efforts of Hey’s Ladies by virtue they were unsullied by professionalism and epitomised a fresh innocence.

Prior to the emergence of either Manningham Ladies or Hey’s Ladies there was little mention of local women’s football in the local press. In fact, I have found no evidence that women’s football was played in Bradford on a competitive basis but this is not surprising in the context of the time. For a start, women tended to enjoy less leisure time than men and were wholly responsible for household duties and childcare. There were also cultural restrictions arising from the expectation of modest clothing being worn which precluded playing football. Notwithstanding there was an active Ladies Hockey League in Bradford which was given coverage by the Yorkshire Sports. Notable is the caption below from 1919.

Ladies’ hockey was also relatively established in Bradford long before football. Furthermore it enjoyed sufficient prestige that in April, 1911 the Manningham Ladies Hockey team was given access to the Park Avenue football ground to play a game with a Derby team.

Standards of endurance fitness among young women were probably also relatively low, an inevitable consequence of limited physical training and exercise. Not only would this have made football more of a daunting physical challenge but it would have been significant in dictating standards of play, irrespective of skills. Similarly, the dominance of rugby and shortage of playing fields in Bradford effectively crowded out the possibility of other games being played, whether men’s soccer or women’s football (by which I refer to both rugby and association codes) and the lack of available opposition would have been another factor. Besides, women’s football was considered a showground spectacle and something that tended to be ridiculed.

Even though Hey’s Ladies were deemed Yorkshire Champions in 1921 (following an emphatic defeat of Doncaster Ladies on Boxing Day), of four games played against Dick, Kerr Ladies in that year, all ended in defeat and the aggregate score was 1-18. Hence without seeking to trivialise the game, it is a fair assumption that footballing standards were poor and it would be foolish to over estimate the quality of women’s football. It is also questionable whether women’s football had become more competitive and whether the participation of women had increased. On 13th April, the Sheffield Daily Telegraph ventured that women’s football had been a product of the war and that a majority of the clubs formed had by then disappeared. For example there is no record of Lister’s Ladies after 1921.

Women’s football in the immediate post-war period comprised only a limited number of teams and of the 67 games played by Dick, Kerr Ladies in 1921 no fewer than 13 had been against St Helens Ladies and a further 16 were played against five other sides, of which Lister’s three times and Hey’s, four times. In 1921 Dick, Kerr Ladies went unbeaten in games against 33 different sides (of which at least 10 had names implying scratch representative teams).

Most of the momentum of women’s football surrounded the phenomenon of Dick, Kerr Ladies who became the face of the women’s game (although between 1916-17 the Portsmouth Ladies side had been equally prominent). In that sense maybe the nearest modern equivalent is that of the basketball side Harlem Globetrotters (albeit without the theatrical routines). The timing of the Football Association ban served to arrest that momentum and by denying access to Football League stadia, restricted the possibility of large crowds attending exhibition matches of women’s football which limited its visibility. By banning the use of pitches registered with Football Association affiliated clubs, the options for where women’s football could be played were further curtailed. The FA also banned its registered referees and linesmen from officiating over women’s football.

Dick, Kerr Ladies had been at the centre of the orbit of women’s football and arguably suffered disproportionately from the FA ban. Within a few years of the ban the team’s profile had become diminished as had public interest in women’s football. In 1921 twenty-five clubs had been represented at a meeting in Bradford to form the English Ladies FA but by the following year this had collapsed and with it a structure that could have co-ordinated the women’s game. In 1926 the Dick, Kerr Ladies side was reincarnated as Preston Ladies and links with the company were severed. Whilst the reasons for this were not disclosed there was inference that the team’s administrator (who had been an employee) had been diverting monies for his own financial benefit, essentially substantiating the original allegations from 1921.

Hey’s Ladies

Unable to use Valley Parade or Park Avenue, Hey’s Ladies staged a game with Dick, Kerr’s in January, 1922 at the Wakefield Trinity RLFC ground at Belle Vue and later adopted the Greenfield Stadium at Dudley Hill. The latter venue actively advertised its facilities for sporting events in the local press and hence would have been particularly receptive to staging women’s football. Crucially however there is no evidence that the Hey’s Ladies club signed a permanent lease at Greenfield as opposed to using the ground on an ‘as and when required’ (and when available) basis. Previously, Hey’s Ladies had been denied use of the Bradford RFC ground at Lidget Green when the Yorkshire RFU refused to sanction access in March, 1922. Hence the option of Greenfield may have been as a last resort and preferable to the Birch Lane ground which was used by Bradford Northern and generally derided.

The incident relating to Lidget Green is another illustration of prevailing attitudes towards women’s football by male sports administrators who harboured historic prejudice. Denied the use of a soccer ground, in March, 1922 Hey’s Ladies had been keen to stage a high profile fixture with French opposition at the recently opened Rugby Union ground in Bradford (Opened in 1919, Lidget Green was considered a prestigious venue as told from this link).

In expressing his opposition to the use of the ground, the longstanding YRFU committee member James Miller was quoted in the Yorkshire Post of 22 March, 1922 that ‘when women tried to play football, they failed, and made a ridiculous exhibition of themselves. He was against encouraging it, for the game of football among women players was neither good for them nor for the game. They were not football matches, but simply woman shows, and they ought not to allow them to make exhibitions of themselves on their grounds. Although the cause – of charity – was right, if people concerned wished to obtain the support of sporting bodies like the Football Association, the Northern Union, and themselves, they must work on different lines.‘ The comments of fellow delegates are equally telling. Rev R Huggard of Barnsley, that ‘it was quite out of place for women to make an exhibition of themselves – and sometimes an unseemly exhibition – on football grounds’ whilst H Duncan of Otley considered that ‘football among women would die a natural death.’

By the time of the Football Association ban at the end of 1921, the Hey’s Ladies side had established itself among the leading clubs in women’s football and this probably had much to do with the energy and enthusiasm of Arthur Hey, general manager of the Hey’s brewery and later to be a director of Bradford City AFC. His initiative most likely explains how Bradford became linked with developments in the women’s game although there is no evidence that participation in the game by women was any higher in Bradford than elsewhere.

An illustration of the status of Hey’s Ladies was the fact that in April, 1923 the club provided the nucleus of the team in a England representative side that played France at the Stade Pershing in Paris, a fixture that was billed locally as an international. (Image below and of the team thanks to Helge Faller.) That game, a 1-0 victory for ‘England’ appears to have been a return match linked to the visit of a touring French side, Olympique de Paris to Bradford in March, 1922. Denied use of Lidget Green, the game had been staged at Greenfield Athletics Stadium.

In April, 1920 Dick, Kerr Ladies had played a series of games with a French touring side in the North West, including one at Deepdale, Preston that had attracted a crowd of 25,000 and this was followed by a tour of France later in the year. The fixtures enjoyed considerable goodwill in England, considered an extension of the wartime friendship and were promoted to raise funds for the rebuilding of Rheims Cathedral. So popular were the games that a series had been organised in 1921 and again in 1922. This then was the context of the visit of the French side to Bradford when 3,000 people were reported to have attended the game at Greenfield, a 2-0 victory for the home side.

It is unclear what were the arrangements for the game in Paris in 1923 and whether the trip was underwritten by Hey’s Brewery. Either way the Hey’s Ladies side became the de facto England team for the occasion.

The football ‘international’ in Paris in April, 1923 was headline billing of a programme of events organised by La Federation Feminine Sportive de France that included basketball and athletics. Nine of the visiting ‘England’ team were regulars with Hey’s Ladies, the others being players from Dick, Kerr Ladies and St Helens.

By 1925 the Hey’s Ladies team had ceased to exist. Any number of reasons could be offered for its demise – the lack of opposition; the failure to secure succession of new players; the cost of staging games at Greenfield; the loss of enthusiasm. In fact few games are recorded to have been played subsequent to the team winning the Whitehead Lifeboat Shield in competition against five other sides in May, 1922. It is notable that the Yorkshire Sports as a dedicated sports newspaper had no coverage of high profile fixtures involving Hey’s players – whether for example the games against French opposition in 1922 and 1923 or the Whitehead tournament at Greenfield. Reports in the daily local papers were basic and matter of fact rather than affording the oxygen of publicity, all of which ensured that public interest remained limited and did nothing to uplift the status of the women’s game.

Exhibition games of women’s football continued to be staged in Bradford on an ad hoc basis. The above cutting for instance is from November, 1932. Similarly the reputation of the former Dick, Kerr side endured and as Preston Ladies they played an exhibition match against a Belgian representative side at Odsal Stadium and in Keighley on successive days in August, 1939. Despite the FA ban, the Odsal match enjoyed the patronage of Bradford football celebrities. David Steele, manager of Bradford Park Avenue was the referee and two Avenue players, Bob Danskin and Chick Farr were linesmen. Present at the game were the directors of both the City and Avenue clubs as well as the Lord Mayor. However a measure of the event was that a local beauty queen performed the ceremonial kick-off.

All of the effort relating to women’s football in Bradford had been concentrated in the two Manningham works sides as distinct from attempts to encourage grass-roots participation by women at playing the game. It seems highly unlikely that any local women’s sides ever existed. There were no league structures and the Bradford & District Football Association which had been established in 1899 to promote soccer – and was evangelical in doing so – played no role in encouraging the women’s game. In all probability the phenomenon of females playing football – if at all – was confined to ad hoc, informal street or playground games among schoolgirls which is a long way removed from organised team football.

Judging from press coverage there appears to have been much greater participation among women in hockey as opposed to football and this was arguably a more common and better established winter sport for women. The fact that it was staged on local cricket grounds also provided opportunities for the sport (ie given a shortage of football playing fields).

The still birth of women’s football in Bradford, as in the rest of England was in good measure due to the prejudice and attitudes of the day handed down from earlier decades. We now consider the local experience of what happened in Bradford prior to the formation of either the Lister’s Ladies or Hay’s Ladies clubs to understand how opinions had been shaped.

The shaping of prejudice towards women’s football

A game at Windhill, Shipley in June, 1881 was possibly the first involving women to be played in Bradford. It was one of a series of exhibition games between teams of women purportedly representing England and Scotland, staged in Scotland the previous month and then across the north of England in Blackpool, Manchester and Blackburn. The fact that Bradford was chosen as part of the tour reflects the fact that it was recognised as a centre of enthusiasm for football. However, this was not an initiative to encourage female participation in football. It was literally a crude commercial entertainment venture to attract a male audience.

Of note, the games in Glasgow and Manchester had provoked crowd disturbances. Newspaper reports are not clear what could have been the cause but it is possible that the crowd had objected to the standard of the entertainment and/or that their expectations had not been met. A common cause of crowd disturbance in the 1880s was to do with betting disputes, invariably because scores were deemed unfavourable or unjust and sometimes grievances that the outcome of the games had been rigged. We can only speculate but for disturbances to have occurred twice inevitably raises suspicions about gambling disputes.

By the time the troupe (that appears to have originated from Glasgow) had arrived in Shipley, provincial newspapers had already railed about the spectacle. The Dundee Courier of 20 May, 1881 for instance commented that ‘the unsuitability of the game to women in every way, for all reasons, is sufficiently obvious’.

The Dublin Daily Express of 23 June, 1881 similarly reported on two of those games that had recently taken place in Manchester, equally dismissive of what had occurred. The reporter referred to the players having been ‘attired in a costume which is neither graceful nor very becoming’ and hinted at lewd display: ‘The score or so of young women who do not hesitate to gratify vulgar curiosity by taking part in what is termed a ladies’ football match.’

Impudent women in unwomanly garb

The account of the Windhill game that appeared in The Yorkshireman of 18 June, 1881 was entirely consistent in expressing its own disapproval. What is unambiguous is that the event was staged solely for the purpose of entertaining a male audience, capitalising on the growing enthusiasm for football. That the game was staged at Windhill as opposed to the district’s premier sporting enclosure at Park Avenue is a demonstration that it was highly unlikely to have been deemed a respectable show.

‘There is no branch of human knowledge, industry, or advancement in which women have not – whilst actuated, no doubt, by that feeling of mental superiority which every one of them feels she possesses over those over-rated and altogether despicable beings, the men – in recent times encroached upon the special privileges of the other sex.

‘I should, with the characteristic blindness and folly of my mindless sex, have imagined her disqualified (to play football).

‘I marvelled much when I heard that a comparatively obscure place like Windhill had been chosen as the scene of an exhibition of so advanced a kind as a female football contest.

‘Reader I know what you will at once ejaculate when you reach this point, ‘What were they like?’ Well, that’s just what I mean to tell you so far as I can. Imagine to yourself a mixture of disbanded ‘extra’ ballet girls, dissipated mill girls, and dubious maidens with light, metallic-looking, dyed, flaxen hair, and usually known as ‘canary birds,’ and let your imagination as much figure as possible – waist sashes, loose flannel breeches reaching to the knees, ordinary coarse striped stockings and unlimited impudence. It was not like football; although the players were evidently purporting to play an ‘Association’ game, it had none of the spirit of the game, for the players – with the exception of one dusky-looking female, with an evident dash of nigger blood in her, who was christened ‘the demon’ – struggled or lolled about in an enervated, half-hearted way. Bless your life, the spectators didn’t attend to see a game of football, they went to see a lot of impudent women in unwomanly garb, and engaged in a brutal occupation.

‘The contending parties professed to represent England and Scotland, but not a man I asked, and I asked many, could tell me which was which, and I doubt if the players themselves knew which side they belonged to. There was palpably no genuine rivalry between the sides except to command the admiration of the male spectators as much as possible. The whole of the players evidently had an impression the plain English of which was ‘We must do something as an excuse for having as little clothing on as possible and acting as little like women as we can.’ And they carried out the idea by listlessly struggling with a ball and, whenever it was at all feasible, getting near the spectators. As to those, they were mostly Bradfordians, fast merchants’ clerks, betting men, publicans, and men about town generally, with a sprinkling of other male individuals who attended out of ‘curiosity.’ I cannot say that all the spectators were youthful, for there were present many men well stricken in years whom no amount of curiosity should have induced to lend countenance to such a display.

‘The character of the show was indicated in the spectators themselves, for throughout the latter there was an all-pervading air of looseness,

‘There were plenty of Germans of course amongst the spectators in the field, and I heard one of them say, ‘All zese girls are in ze game vat you call ‘forwards’. I suppose.’ All around the field a running fire of coarse comments was kept up by the spectators.

‘It beats cock fighting into fits, enthusiastically claimed a dirty man, clothed in a seedy check suit.

‘At last the game was concluded and the players all made a rush for the gate. As they ran so did the spectators and, incredible as it may seem, many of the latter seized the former bodily and hugged them amorously.

‘I turned towards Bradford, asking myself whether this show will not inaugurate a new phase in the already pretty extensive list of degrading amusements, and whether we shall not ere long be subjected to female cricket matches, and swimming contests, and athletic sports and, well, I really dare not picture even to myself what besides.’

A further example is that of another exhibition game by the so-called ‘Lady Footballers’ at Valley Parade in May, 1895. This was part of a series of matches organised by a group of female footballers as a commercial venture and they toured the country to exploit the curiosity of people in women’s football. It was again another showground spectacle and it is unambiguous that the crowd had not assembled for the purpose of watching a competitive contest or to witness a game of soccer (at that time a code uncommon in Bradford).

A miserable travesty of a splendid game

The following is the report from the Bradford Daily Telegraph on 8 May, 1895:

‘Although the visit of the Lady Footballers to Valley Parade last night had only been advertised for one day a crowd of between 2,000 and 3,000 people turned up to see the fun. It was fun that was expected by the spectators, and fun was all that was forthcoming, the attempts at football being feeble and farcical.

There was nothing in the costume of the lady footballers to shock the sensibilities of Mrs Grundy, but all the same the attire is not likely to become popular with the fair sex, for the simple reason that it is not becoming. Had the lady footballers been less favoured by Nature they would have presented a ‘dowdy’ appearance, but the natural beauty and grace of several saved the team from this.

To the regret of many Rugbyites the ladies played yesterday evening under Association rules, and owing to the half-hearted way in which most of the players entered into their work the exhibition at times fell woefully flat. Several members of the team seemed, as the crowd put it, afraid of hurting the ball, and they persistently refused to ‘give it boot.’

The kicking of some was so gentle as to suggest parlour football, but there was one exception. A young girl operating on the left wing, who was styled ‘Tommy’ by the London spectators under the belief that she was a boy, put in a lot of dashing play and fairly roused the crowd from its lethargy to cheering. She was certainly worth any three of the other players, but at the same time it should be said that one or two other players did not ‘frame’ at all badly.

The great drawback to ladies’ football, however, seems to lie in the fact that it seems a physical impossibility for ladies to run quickly and gracefully. As an exhibition of football the play was a miserable travesty of a splendid game and as an entertainment it soon became tedious.’

The game would have been the first soccer match to have been staged at Valley Parade although the historic significance was not recognised at the time (or subsequently). A further point to note is that for Manningham FC to have consented to host the event would imply that there were no misgivings about decency. (The organiser was the so-called British Ladies Football Club that had been formed in January, 1895 and which toured Great Britain during its brief existence until around September, 1896. Having been established by a woman with an upper class background, and with a genuine commitment to playing football, the project was afforded a degree of respectability despite being unashamedly commercial in nature.)

A weakness for gossiping

In common with other British towns, women’s football became more common during World War One with games staged between factory teams, invariably to raise funds for war charities. The comments below from the (Bradford) Yorkshire Sports in December, 1916 confirm that women’s football was not taken seriously and that there were no pretensions for it to be treated as an equivalent to the male game.

It is noteworthy that the writer thought fit to make comparison with the earlier tour by the British Ladies Football Club of 1895. What is striking is not so much the condescending language, rather the fact that the tour remained uppermost in the mind of football commentators and influencers. Yet the extraordinary phenomenon of women’s football was still considered deserving of column inches elsewhere in the paper, even if they only served to provide further mockery.

In August, 1917 a women’s game was staged at Park Avenue between two works sides representing the Phoenix Dynamo Company and Thwaites. Again, newspaper reports hint that the game was an entertainment spectacle rather than a competitive contest of skill. The Leeds Mercury of 7 August, 1917 pointedly referred to the women footballers that ‘their methods were not quite orthodox’ but was more charitable in acknowledging the entertainment: ‘Apart from a weakness for gossiping with the crowd when they ought to have been getting on with the game, they did very well, and the fun never waned.’

It will be noted that unlike in 1881, or even 1895, in 1917 there was no suggestion of social impropriety. Whilst this reflected that attitudes had changed and that it might now be considered harmless fun, justification for the activity was also derived from the fact that it was linked to the war effort. Yet the above reports from 1916 and 1917 were still dismissive about the merits of women’s football and it is therefore easy to see how prejudices would have been shaped about women’s football ahead of the Football Association ban in 1921. Indeed there is no reason to believe that attitudes in Bradford were any different to those elsewhere.

Shows of pure burlesque?

A further dimension to the prejudice is illustrated by another example of what happened in Bradford, this time with regards to the Football Association’s response to the staging of pantomime soccer games at Valley Parade in 1907. Annual pantomime charity football matches had been held at the end of the panto season in February between artistes in costume from the rival Bradford shows. The tradition had begun at Valley Parade in 1891 (presumably on account of proximity to theatres on Manningham Lane) but had then been staged at Park Avenue from 1893. The fixture was revived at Valley Parade after the conversion of Manningham FC to soccer in 1903 but in February, 1907 the Football Association adopted a rather highbrow attitude and was reported to have ‘intimated that they did not wish the game to become pure burlesque.’ I should imagine that women’s football was similarly dismissed as burlesque.

The following caption from May, 1920 provides clues as to the perceived sexualisation of football and the concern that this may have caused the FA.

A Craze of the Future?

In spite of the negativity, a correspondent to the Yorkshire Sports in June, 1917 had ventured that there might be a future for women’s football, even though contemporary medical opinion suggested that some form of modification was necessary. In the final event the Football Association would never have sanctioned such changes to the sanctity of the game and nor would existing professional clubs have tolerated the emergence of a competitive threat. In the context of the time therefore, the subsequent FA ban seems entirely understandable.

(NB The Northern Union had felt obliged to make a series of changes to the rules of traditional rugby (union) for its code, the most obvious of which being a switch to thirteen aside in 1906. These changes were considered necessary to maintain the interest of the public in the face of competition from soccer and the Football Association might reasonably have considered that a similar threat would emerge in relation to its own rules if the women’s game was encouraged.)

What might have happened?

How women’s football might have developed had there not been a Football Association ban is a matter of conjecture but it is intriguing to consider the local implications. There had already been a fragmentation of sporting options in Bradford at the beginning of the 1920s. Bradford City and Bradford Park Avenue faced competition not just from Bradford Northern RFC, but also from a resurgent interest in rugby union and a revived Bradford rugby club at Lidget Green. Might attendances at Valley Parade or Park Avenue have been cannibalised by women’s football had the FA ban not been imposed or would the novelty of women’s football have simply worn off?

There are parallels in West Yorkshire between the Football Association’s attempt to suffocate women’s football in 1921 and with what had happened towards the end of the nineteenth century when it was widely felt that senior Northern Union (rugby) clubs had deliberately acted to discourage the take-up of association football through withdrawal of support to their own soccer sides. Yet while women’s football was denied an umbilical cord in 1921, the history of Bradford soccer suggests that more would have been necessary for women’s football to thrive and participation to be encouraged at a grass-roots level.

In Bradford at the beginning of the twentieth century, leaders of the Bradford & District FA – so-called associationists – recognised that for soccer to take hold in a rugby stronghold would require deep foundations. Critical success factors that they identified included the supply of local players, a suitably competitive league / cup infrastructure and a network of evenly matched teams to raise standards, the oxygen of local press coverage as well as the inspiration of a local professional club. The association itself was equally important in order to provide effective leadership and promote the sport. Much the same would have been necessary for women’s football to become established.

With regards local press coverage, there was infrequent photographic coverage of women’s football in the Yorkshire Sports during spring 1921 which happened to be when the paper was expanding photo content and was in parallel to occasional photographic coverage of women’s hockey, tennis and cricket teams. That there were no match reports or extensive comment about the subsequent ban on women’s football in the same title confirms that it was still not an activity taken seriously. In July, 1922 a game between Hey’s Ladies and a celebrity Jockeys XI at Greenfield (Dudley Hill) epitomised the status of women’s football in Bradford – photographs from the Yorkshire Sports of 8th July, 1922 below.

Undoubtedly the Football Association ban was damaging by preventing prestige exhibition matches and the corresponding visibility and inspiration that they might provide. There was further harm arising from restrictions on junior soccer clubs sponsoring women’s football through sharing facilities. Nevertheless there were other major obstacles to the promotion of women’s football at a grass roots level. For instance, the Bradford & District FA had attached considerable importance to the schoolboy game as a means of propagating enthusiasm and new talent but schoolgirl sport would continue to be undeveloped for a long time to come. (For that matter there were insufficient playing fields in Bradford for existing school needs with much reliance upon the city’s main parks. This was a factor that assisted the spread of women’s hockey given that it was played on cricket grounds.)

Even if the Football Association had not enforced its ban, women’s football surely lacked the necessary ingredients and local foundations to establish and sustain itself at a national level. There were also challenges for senior, elite clubs to become established. In particular it was acknowledged that the strength of the Dick, Kerr team was due to the willingness and ability of the firm to pay good wages to talented footballers. Crucially, women’s football would have continued to remain dependent upon the sponsorship of employers to support players and be sympathetic to them having time off work – this was because there was little prospect that professionalism would have been a viable option for many players or women’s sides as stand alone entities. Likewise, as had been the case in the second half of the 1890s, emergent soccer clubs would remain beholden upon the support of professional (Football League or Northern Union/Rugby League) clubs for the use of stadia if a breakthrough in support was to be achieved. As the experience in West Yorkshire in the previous century had demonstrated, those professional clubs had the means at their disposal to prevent the prospect of a competitor attraction becoming established and refuse ground sharing. Even without an FA ban, women’s football needed the enduring goodwill of the men’s game.

The sheer dominance of Dick, Kerr Ladies also highlighted that at a national level women’s football was far from being broadly based to provide compelling interest in league or cup competitions as a means to regularly attract spectators. The novelty value of women’s football would probably have worn off in the absence of new teams emerging or a change in the format of the game away from reliance on exhibition matches.

Women’s football would have been vulnerable to competition and in all likelihood, would have faced adverse comparison with other forms of football as spectator attractions, judged on the standard of game being played. Because women’s football would have struggled to become professionalised, how could it have raised standards to compete with the men’s game? As an entertainment business, women’s football would have faced further competition from emergent attractions such as greyhounds and speedway as well as the rise of the cinema. Consequently it would have been difficult for the game to secure a profitable niche with men’s football and rugby having established support and traditions to rely upon. In other words the commercial opportunities in the inter-war period were limited.

Locally, sentimentalism about the Hey’s Ladies phenomenon has to be balanced with the cold financial reality and it is fanciful to believe that the women’s game could have thrived in Bradford or the country as a whole. Indeed, it would take at least five decades for a supportive environment to evolve. It was not simply that women’s football required a change in cultural attitudes and social acceptance as a competitive sport, it also needed the economic fundamentals to be in place.

Conclusions

Without wishing to appear dismissive, I believe the emergent craze for women’s football in the aftermath of World War One would have petered out almost as dramatically as it had begun, even without the Football Association ban. In Bradford the shifting fortunes of soccer, amateur rugby and then professional rugby in the inter-war years demonstrate that ‘football’ was subject to changing fashions and popularity. How could women’s football have been immune if it was to avoid resorting to being a showground spectacle or lobbying for a change of rules?

Thus my belief is that the infamous ban was far from being the only factor in the still birth of women’s football at a senior level. Furthermore, whilst the Football Association ban might well be deemed indefensible by modern standards, we need to accept that the context of its enforcement was entirely different and take account of the historical setting of the prejudices and circumstances at that time. As I have sought to demonstrate, what happened in Bradford provides insight into that historical context.

by John Dewhirst

@jpdewhirst

Yorkshire Sports 16 April, 1921

=======================================================================

Other online articles about Bradford sport by the same author

John contributes to the Bradford City match day programme. You will find these, book reviews and other features on his blog Wool City Rivals.

Included on the blog is his review of The History of Women’s Football by Jean Williams (2021)

=======================================================================

You will find articles about a broad range of sports on VINCIT with new features published every two to three weeks. We welcome contributions about the sporting history of Bradford and are happy to feature any sport or club provided it has a Bradford heritage.

Planned articles in the next few months include features on the impact of the railways on Bradford sport; the political background to the history of Odsal Stadium; Bradford soccer clubs in the 1880s and 1890s; the story of Shipley FC; the impact of social networks on the early development of Bradford sport; amateur football in the Bradford district; and a compendium of Bradford sports stadia.

=======================================================================

Details about the BANTAMSPAST HISTORY REVISITED BOOKS

=======================================================================