The Centenary of the Bradford Rugby Revival

This month marks the centenary of the opening of the Scholemoor ground in Lidget Green in March, 1919 and the revival of a Bradford Rugby Union club as successor to the former (amateur) Bradford FC.

During the first decade of the twentieth century there were frustrated attempts to revive Rugby Union in the Bradford district, principally through the Bradford Wanderers and Horton clubs [1] and in 1907 there had been hopes of restoring the amateur code to Park Avenue. Those efforts reflected an underlying dissatisfaction among traditional rugby followers that the Northern Union had proved lacking and was a poor alternative to the traditional code. The criticisms of the professional game were various, foremost of which was a distaste for how rugby had become commercialised that critics believed was to the detriment of the game itself.Going back to the immediate aftermath of the so-called ‘Great Split’ in 1895, the breakaway rebels had alienated followers of the junior sides who blamed the Northern Union for the financial difficulties of their clubs. [2] By the end of the nineteenth century most had succumbed to insolvency and it remained a grudge against the Northern Union that the juniors had disappeared. To be fair, most of those clubs were financially vulnerable well before the Northern Union came about but the rupture in 1895 made survival a more difficult task. [3]

The rule changes of the Northern Union including the introduction of thirteen aside in 1906 had also alienated rugby fans. In Bradford, and at Park Avenue in particular, much of the antipathy towards the Northern Union had arisen from the fact that whereas prior to 1895 Bradford FC had enjoyed a prestigious fixture card with games against the leading sides of Scotland, Wales and southern England, within the Northern Union there was much less variety or glamour.

As I highlight in LIFE AT THE TOP [4], the tension between the professional and amateur variants of the game was not entirely a matter of class antagonism. Indeed, the experience in Bradford suggests that class identity and mockery of social mores did not become a part of the rivalry between the two codes until around 1905. This phenomenon had much to do with the Northern Union losing its appeal to the public who opted instead for association football and locally, the launch of Bradford City AFC at Valley Parade in 1903 had prompted the desertion of spectators from Park Avenue. In response, the Northern Union sought to promote itself as the peoples’ game. Whilst this made little impact on the popularity of the Northern Union in relation to soccer, it served to differentiate the Northern Union from the Rugby Union in so far as by 1905 the latter game had become a distinctly middle class pursuit. Indeed, whereas many of the junior clubs in the Bradford district who had continued to play Rugby Union after 1895 could be described as working class in their composition, after their disappearance by the end of that decade, Rugby Union in Yorkshire was played almost exclusively by public schools (ie Bradford Grammar School and Woodhouse Grove) and their alumni. However to suggest that after 1895 working class people in Bradford had no affection for traditional rugby – played according to Rugby Union rules – is misleading.

Prior to World War One, the efforts to sustain a vibrant Rugby Union club in Bradford had floundered on two fundamental issues. The first was the lack of a centrally located ground. The second was the difficulty recruiting new players given that the game did not have the catchment of many young players in the district unlike for example during the 1880s. The issue of where Rugby Union was played was another factor in this in so far as a central ground would have made it more convenient to attract potential recruits. Not surprisingly, those efforts to revive Rugby Union in Bradford prior to World War One made little headway. Ironically, land for a new ground at Lidget Green overlooking the Scholemoor cemetery had been secured in May, 1914 but the outbreak of hostilities three months’ later meant that plans for its development were put on hold. Horton RUFC, the leading side in the district that would have played at the ground, quite possibly relaunching itself as ‘Bradford’.

A new enthusiasm for Rugby Union

By the end of the war the circumstances were better suited to reviving a Bradford Rugby Union club as a successor to the original Bradford FC that had played at Park Avenue. Although the war may have helped reconnect men with Rugby Union (as the game of choice in the armed services), the change in attitude was probably more to do with idealised notions of what the peace should bring and of how sport might contribute to building a brave new world. During 1917 and 1918, editorials in the Yorkshire Sports were already giving thought to peacetime sport. Boxing for example was identified as likely to be popular, presumably because participation had been encouraged in the army [5]. Rugby Union football had similarly been promoted by the armed services and rugby historian Tony Collins has explained how World War One raised the prestige of Rugby Union as the winter sport of the military. [6]

The high casualty rates among rugby players had raised the prestige of the sport. Indeed, Horton RUFC was probably the worst affected of all Bradford sports clubs by the conflict and it was claimed that as many as 15 of the 59 members were killed in World War One and a further 20 had been wounded. This sacrifice further encouraged the efforts to revive Rugby Union in the city and it was considered a gesture of appreciation to the fighting men to endow Bradford with a rugby club to provide the opportunity for future comradeship, recreation and glory. Whilst these were lofty ideals there was a public mood to aspire to something noble that helped reconcile minds to the sacrifice of armed conflict having being worthwhile [7]. This phenomenon was not confined to Bradford and as soon as peace was declared there was news of Rugby Union clubs being revived, among them Bristol and Leicester both of whom announced plans within days of the Armistice.

The Lidget Green site had been waste land but work began in 1918 to drain and level. The Yorkshire Post of 20th January, 1919 reported that the pitch was ‘on a broad plateau overlooking the Thornton Valley with a beautiful and bracing situation’! The terracing was based on ash banks. A total of £3,000 had been spent on the ground with ‘requisite funds forthcoming from gentlemen in Bradford who feel the necessity for encouraging amateur sport in the city and the neighbourhood.’ It was noted that ‘there had been no appeal for funds, such was not desired, nor was it necessary.’ [8]

Bradford derived a fillip from the new ground being selected as a venue for games in the King’s Cup tournament that was staged in March, 1919 between military sides representing the white Dominions of the British Empire – Australia, Canada, South Africa and New Zealand as well as representatives of the ‘Mother Country’ and the RAF . The competition has been described as rugby’s first ‘World Cup’ whereas it was promoted to bolster imperial unity and excluded non-Empire sides, the most obvious of which being France. Bradford was the only northern venue for the King’s Cup [9] which was quite a coup and this provided the impulse to attract recruits for a new Bradford Rugby Union club that became known simply as ‘Bradford Rugby’.

In Bradford there was a particular affinity with Rugby Union dating back 35 years to when Bradford established for itself a reputation as a rugby hotspot, not due simply to the achievements of Bradford FC or latterly Manningham FC, but the fact that the game was well-established with a strong football culture in the town. For instance there had been a multitude of clubs at junior and local level considered to be of decent standard. Journalists from other towns frequently remarked on the enthusiasm for the game in Bradford. Rugby football had played a big role in defining a Bradford identity and the players of Bradford FC who won the Yorkshire Cup in 1884 had achieved celebrity status. Of the two rival clubs, Bradford FC had by far a more glamorous reputation than Manningham FC. Bradford FC, based at the prestigious Park Avenue ground was considered the town club and its success winning the Yorkshire Challenge Cup in 1884 was the catalyst for prominence on a national stage. Inevitably there were fond memories of the good times when Bradford had commanded such attention.

The legend of Bradford’s rugby history was a source of pride, a reminder of the city’s former greatness and it is not surprising then that nostalgia for those glory years should have had emotional appeal amidst the trauma of war. Prior to the outbreak of the conflict in 1914 there had been a mood of self-confidence in the city that was enjoying a period of economic prosperity and cultural vitality. In other words the rekindling of enthusiasm for Rugby Union and talk of a revived club in Bradford was aligned with the mood of the time to build for the future and restore what had previously been lost.

Reactions to the Rugby Union revival

In all likelihood the nostalgia for amateur rugby was greatest among those in late middle age with misty-eyed recollections of their youth. It seems unlikely to have been shared equally by former partisan Manningham FC members who had long since reconciled themselves to soccer. Their own club had been transformed into one of the leading sides in the Football League, FA Cup winners in 1911 and members of Division One since 1908. Rugby Union (and rugby in general) was viewed as irrelevant and City supporters would have been indifferent to the code’s revival.

Bradford City AFC was by now well-established and thoughts for the future were firmly about carrying on from where things had been left. A good number of the Valley Parade heroes from those heady days were still part of the club and in 1919/20 for instance, eight players who had represented City in the last regular season, 1914/15 provided the nucleus of the first team. Conspicuous by his absence however was Bob Torrance, who had made been killed in action near Ypres in April, 1918. For all involved with the club it must have been a difficult experience but presumably one that encouraged a close bond between players and supporters.

Although supporters of Bradford Park Avenue would have been similarly dismissive about rugby, the leadership of the club was nonetheless sensitive about the revival of a Bradford Rugby Union club. The ‘Great Betrayal’ of 1907 had been controversial and divisive in equal measure as well as fresh in the memory. Park Avenue remained the de facto spiritual home of Bradford sport and Bradford Park Avenue AFC still had ambitions of establishing itself as the senior association club in the city (and by virtue of having finished above Bradford City in the last peacetime season of the Football League it was not an unrealistic objective).

The relative status of football clubs in Bradford had been an emotive topic going back to the original rivalry of Manningham FC and Bradford FC. What Bradford Park Avenue AFC did not want was a resurgent Bradford Rugby club laying claim to inheriting the mantle as natural successors to Bradford FC and usurping its own pretensions, let alone laying claim to Park Avenue as potential tenants. Such was the insecurity at Bradford Park Avenue AFC that the proximity of Bradford Rugby’s Scholemoor ground at Lidget Green to Park Avenue (less than a mile) was also viewed as a threat to its gates. In the Yorkshire Evening Post of 15th March, 1919 Harry Briggs was anxious to dismiss the suggestion that his club was antagonistic to the new venture and offered the use of Park Avenue to the new Bradford Rugby club should it be necessary.

As for Bradford Northern RFC, ever since formation in 1907 (after the ‘Great Betrayal’ at Park Avenue when rugby was abandoned in favour of soccer) the club had struggled to remain a viable entity and during the war there was even talk of disbanding. It had been kept alive through the efforts of its members and directors whose attitude towards Rugby Union could be described as cynical and suspicious if not hostile. Noteworthy is that the Bradford Northern club of the time had much in common with the original Bradford FC when it had been in its prime given that the majority of its players were of local origin. There was the suggestion among Northern Union followers that a new Bradford Rugby Union club would be a positive development in that it might be a source of new talent and the recruitment of players. Despite the bravado, a new rugby club in the city would have constituted a threat to Bradford Northern. Considered one of the weaker sides, Bradford Northern had been perennial strugglers in the Northern Union since formation and the chances of the club providing displays of exhibition rugby were remote. Thus Bradford Northern was vulnerable to the emergence of a decent Bradford Rugby Union club that would make it even more reliant on its partisan followers and the Birch Lane club was less likely to attract those floating spectators who were now offered another option for Saturday afternoon winter entertainment.

What enthusiasts of each of the football codes – Association, Rugby Union and Northern Union – had in common after the hardship of war was a desire to get back to normal. Nothing epitomised that better than the opportunity to watch their favourite game. Thus 1919 and the resumption of peacetime competition was a fresh start for all and the 1919/20 season was one of the most eagerly anticipated by each Bradford club. Other peacetime recreational habits were revived included the reintroduction of trotting races at Greenfield, Dudley Hill in March, 1919 after a break of two years.

Hickson’s Leadership

What is important to understand is that the original ascendancy of Bradford FC had been a very local affair. The heroes of the 1884 team were mostly Bradford men who continued to live in the area. The role of Laurie Hickson, President of the Yorkshire RFU in the revival of the amateur game in Bradford is deserving of particular mention and it was his status within the RFU hierarchy that would have secured Bradford’s involvement in the prestigious King’s Cup tournament. (To my knowledge it is the only time that a Bradford sports ground has hosted ties in an international tournament involving national representatives.)

Hickson had signed for Bradford FC from Bingley FC in 1882 at the age of 21. During a ten year career he was a member of the club’s 1884 Yorkshire Cup winning side and was selected 6 times for England between 1887-90, once as captain. During this time he participated in the club’s high profile tours and fixtures at Park Avenue against leading sides from England, Scotland and Wales. In 1890 he was made a founder member of the Barbarians having been present at the dinner in Bradford at which the touring club was conceived.

After retirement as a player he remained closely involved with affairs at Park Avenue, elected to the leadership committee. However he did not sever his connections in 1895 when Bradford FC seceded from the Rugby Union and remained a member of the powerful Finance & Property Committee of the Bradford Cricket, Athletic & Football Club from its creation in 1892. He likewise remained a Vice President of the club until 1907 when in that same year he argued passionately for a return to Rugby Union at Park Avenue. At one stage it seemed that he might be successful but his campaigning made him subject to ridicule and critics argued against him that Rugby Union could never be made to pay if the code was restored. In 1919 this would have made him all the more determined to prove otherwise that the amateur game could be re-established at a senior level in Bradford and Hickson would have realised that he would never have a better chance to do so.

Hickson (pictured, left above) provided the figurehead, fronting a leadership group that included other former members of the Bradford Cricket, Athletic & Football Club, among them Edward Airey, a former treasurer and committee man (pictured, right) as well as Herbert Robertshaw, a former teammate (pictured, middle). All three were also respected industrialists in Bradford. Hickson and Robertshaw’s involvement personified the golden era of Bradford rugby and its traditions. Crucially they were men capable of delivering the project in a manner that the 1884 team captain, Fred Bonsor could not. Prior to 1907 Bonsor had frequently been the champion of Rugby Union in the Bradford /Leeds press. However he did so in a manner that discredited his cause through unrestrained criticism of the Northern Union and repetitive talk of the good old days that must surely have been considered tiresome. By contrast Hickson was able to articulate a vision for the revival of Rugby Union in Bradford. Besides, in 1908 Bonsor had returned once again to Canada to make his fortune as a farmer on the prairies such that he could not embarrass the Bradford Rugby Union promoters. Admittedly Hickson’s vision for Rugby Union was heavily idealised and derived its succour from mythical content. Yet whilst we can be cynical, people were genuinely receptive to the notion of rediscovering the past and deriving comfort from a period that was fondly remembered. At a time of considerable trauma after the circumstances of war it was hardly surprising that there should be such an impulse.

The cult of athleticism in the nineteenth century had fostered notions of how sport benefited participants through healthy and purposeful recreation. It was also considered an expression of civic patriotism and all of this was at the heart of Hickson’s vision. Equally Hickson was against the corruption of sport through commercial interest and pursuit of the profit motive. (Instead, the traditional belief was that any monetary operating surplus should be contributed towards charity.) His championing of amateur Rugby Union was likewise a rejection of professionalism as well as gambling. Not only did this distinguish Rugby Union from the Northern Union code but also in relation to professional (association) football. Of course sport had been encouraged as a means of physical well-meaning with patriotic benefit for the defence of hearth and home through armed service. For Hickson, a Lieutenant-Colonel in the volunteer territorials who had lost a son in the war, this was another theme that had resonance.

Hickson was a prominent Conservative in Bradford but it would be wrong to suggest that enthusiasm for Rugby Union in Bradford was monopolised by Tories despite its imperial associations. An illustration of this was provided by the example of Alderman Joseph Hayhurst, installed as Bradford’s first Labour Lord Mayor on 9th November, 1918 only two days before the end of war. By background Hayhurst was General Secretary of the Amalgamated Society of Dyers and he confessed a love of Rugby Union from having followed Bradford FC and Manningham FC in his youth. As Lord Mayor he was called upon to be the civic dignitary at the opening of the Scholemoor ground in March, 1919 and did not spare effusive comments about the game. Sadly Hayhurst died in office only three months later on 13th June.

During the summer of 1919 Hickson also had a lead role in the efforts to revive Bradford cricket. In 1915 Bradford Cricket Club had been wound up and by the end of the war its ground at Park Avenue was in need of major repair. Hickson became involved in discussions with Harry Briggs to buy the freehold and as with the Scholemoor initiative, Hickson became a trustee in the eventual purchase in 1920. Although the new Bradford RFC and revived Bradford Cricket Club had common support they remained independent entities and there was no suggestion of re-establishing the merged organisation that had been formed at Park Avenue in 1880 and which existed until 1907. With regards Bradford cricket, there was an uncanny resemblance to the efforts of Bob Appleyard and his ‘Friends of Park Avenue’ campaign in 1986 with Hickson similarly acting to safeguard the ground as a cricket venue in 1919. On his death in August, 1920 Hickson was rightly acclaimed for his contribution to the sporting life of Bradford and his various efforts should be remembered for having played a big part in the recovery of the city from war and the transition to peace. Three of his sons – Lawrie, Stanley and Fred – subsequently played for Bradford Rugby.

Ground opening

The opening game for the Scholemoor ground at Dracup Avenue, Lidget Green was on 8th March, 1919 for a challenge match between representative teams of Yorkshire and New Zealand, the latter ‘All Blacks’ comprising members of the New Zealand military. The Yorkshire Evening Post of 7th March had reported that ‘the Colonials visit marks the commencement of a new era in Bradford, or rather the revival of an old, for the real Rugby game is to be given a fresh start‘. It was a prestige fixture, all the more remarkable for the fact that on the same day New Zealand were due to play Canada at Portsmouth in the King’s Cup and yet they fielded the strongest side in Bradford.

The Lord Mayor, Alderman Joseph Hayhurst conducted a brief ceremony (at which the Lord Mayor of Leeds was also present) before the game and celebrations continued after the match in a style reminiscent of the original Bradford club, involving dinner at the Talbot Hotel followed by a smoking concert. Laurie Hickson proclaimed that the ground had been opened with the sole objective of catering for amateurs but that the club was not to be run with the intention of making a profit. The Lord Mayor’s language was entirely consistent with that of Hickson, adding that ‘the old Bradford club had bred real men, and in the days to come he hoped equally thrilling stories would be told about the true sporting ways of the present day amateurs’ adding ‘there will be no squaring of matches here. Bookies will not be known.’ He said that he was reminded of the 1881-90 era, the ‘great days of the old Bradford Club… in those days they were all hero worshippers, and used to pay homage to such names as Bonsor, the brothers Robertshaw, Ritchie and Hickson.’

It represented a yearning for a sporting idyll, free from the corruption of money-making or gambling. In his speech Alderman Hayhurst declared that ‘the ground would be used for the development of physique and pure sport and spectators could be sure of the best team winning. The public would find pure relaxation.’ It was as if the clock could be turned back before rugby had become commercialised.

However if ever there was a mythical golden era of sportsmanship in Bradford rugby it would have been the first half of the 1870s before Hickson and Robertshaw had played for Bradford FC. Instead, local nostalgia was focused on a supposed golden era in the following decade when Hickson had coincidentally been in his prime. This overlooked the fact that the game had rapidly become commercialised in the 1880s and by the middle of that decade traditional ideals were increasingly only being paid lip service. Indeed there were emergent contradictions, the most obvious of which was that lease commitments pushed clubs towards commercialisation. In turn the commitment to charitable giving was sacrificed to the obligation to repayment of monies borrowed to develop grounds. However what older generations of Bradfordians recalled was that the 1880s had been a decade in which Bradford FC had been known as one of the top sides in Great Britain. That above all else ensured that memories of the era would be cherished.

It was incidental that the Yorkshire side was heavily defeated 5-44 in the contest with the New Zealanders. What was more significant was that the game attracted a crowd of 10,000, confirming local interest in the revival of rugby traditions in Bradford. It was reported that there was a reunion of old supporters from the days of rugby pre-1907 at Park Avenue (which must have been similar to the reunion of former followers of the original (1908-74) Bradford Park Avenue AFC when it reformed in 1988).

The gate receipts of £355 were said to have been the highest for a rugby match in the city since 1906. Inevitably it raised hopes among advocates of Rugby Union that their code would usurp the rival variant in Bradford. Praise was also given to the Lidget Green ground and whilst it did not have the grandeur of Park Avenue, it would have compared favourably with Birch Lane, home of Bradford Northern. The directors of the latter must have looked on with jealousy, regretting that their own club was not similarly blessed.

A fortnight later, on 22nd March the planned game between the Australia and New Zealand military teams at Lidget Green was postponed on account of snowfall and it was eventually played on 12th April (a 6-5 victory by Australia) in front of a crowd reported to be ‘six to eight thousand’ in size. It was a shock defeat but on 16th April, New Zealand defeated the Mother Country to win the King’s Cup at Twickenham. [10]

Fullback, Captain Bruce ‘Jackie’ Beith is tackled in the match between Australia and New Zealand at Bradford on 9th April, 1919. Identified: 1. A. Wilson, New Zealand (NZ); 2. Referee Mr Yeadon; 3. Private A. Singe, NZ forward; 4. Captain Bruce ‘Jackie’ Beith; 5. unidentified NZ forward; 6. Sergeant Joseph Murray; 7. Corporal Vivian ‘Viv’ Dunn; 8. R. Sellars, NZ; 9. unidentified NZ, obscured; 10. Lieutenant Horace ‘Dick’ Pountney; 11. Lieutenant Ernest ‘Bill’ Cody; 12. Ernest ‘Moke’ Belliss, NZ. (Thanks to Phil Atkinson for the photo.)

Bradford Rugby Club played its first game on 29th March against a scratch team selected by the Yorkshire Rugby Union secretary, RF Oates in which the home side succumbed to a 8-24 defeat.

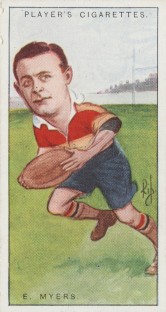

The new Bradford club drew upon the nucleus of the former Horton RUFC albeit whose membership had been depleted in the war. The star player was Eddie Myers, a Bradford man who had previously played for Headingley and who won the first of 18 England caps as a Bradford player in 1920. The launch of Bradford RUFC in 1919 encouraged interest in Rugby Union and it is no coincidence that another longstanding club in the district, Bradford Salem RUFC was formed shortly afterwards in 1924. The current Keighley rugby union club dates from 1920 and Bingley RUFC was similarly revived in 1922. [11]

In 1923 Bradford RUFC emulated Bradford FC’s achievement in 1884 by winning the Yorkshire Challenge Cup, admittedly by then not as competitively contested. Between 1923-25 Bradford set a new record by winning the cup in three successive seasons (photograph below of the 1925 final at Ilkley) and it was reported that its games often attracted five figure attendances. New Zealand sides returned in 1924, 1926 and 1935.

The facilities at the ground remained basic but they were sufficient for the club’s needs and allowed it to remain independent. The North Stand was re-erected from Peel Park having previously been used for galas and in 1923 the club erected a covered stand on the south side at Scholemoor (see photo below – a structure that became prone to vandalism and was eventually declared unsafe and condemned in the 1970s). The club’s reserve pitch was off Hollingworth Lane but the use of this was lost in the 1950s when it was developed for warehousing by Fields (printers).

During the club’s first decade of existence there is a good chance that it cannibalised attendances at the other senior Bradford clubs. To what extent is impossible to say but in the first half of the 1920s the success of Bradford Rugby contrasted with the doldrums of the other three who were each struggling and downwardly mobile.

The revitalisation of Avenue in 1927/28 and then City in 1928/29 restored the old order. By this time Bradford Rugby was already beginning to fade and could no longer be considered a threat.

The fate of Bradford Rugby

In the 1930s Bradford RUFC drifted out of favour with the Bradford public, for whom it was simply another entertainment option. There were a number of reasons for this, the first was that fashions changed and in Bradford it tended to be the case that public affection switched between the four senior clubs – Bradford City, Bradford Park Avenue, Bradford Northern and Bradford Rugby – each of whom competed for attention. After the opening of Odsal in 1934 for example, Rugby League became the most popular rugby code in the city and even began to attract spectators from the round ball game. Secondly, Bradford RUFC struggled to recruit sufficient players of good standard to ensure succession planning. A third handicap was the club’s location. Whilst Scholemoor was adequate as a basic ground, within ten years it was surrounded by housing that created practical difficulties of access and parking as well as the later problem of persistent vandalism. Similarly, with no suitable facilities nearby the club became forced to rely on fields across the city to stage reserve and youth team games (latterly the King George V playing fields off Canal Road). This made it difficult to co-ordinate activities, for example to fulfil parallel fixtures involving first team and reserve fixtures and it also compromised options for training and the development of juniors.

Whilst Bradford RUFC eschewed professionalism and commercial activity it still faced financial obligations for the upkeep of its ground. There was no escaping the financial imperative to make a surplus to fund those commitments. By the late 1930s ‘Bradford Rugby’ (as Bradford RUFC became known) was struggling to attract public interest, finding it difficult to recruit new players and was having to appeal to the goodwill of its members to remain solvent. Despite its early promise in the 1920s, thereafter it became relatively insignificant in terms of sporting interest beyond its own membership and a hardcore of Rugby Union enthusiasts. Nevertheless, Scholemoor continued to host prestige county games that attracted decent crowds. In September, 1935 the ground hosted the All Blacks who played a game against a combined Yorkshire & Cumberland XV which was attended by 16,000 spectators.

In February, 1954 another capacity 16,000 crowd attended a game between the NE Counties and the All Blacks in the 21st game of their tour which the visitors won 16-0 to remain undefeated in England. An eight ton road roller was used to help prepare the pitch after a heavy frost and this was later blamed for crushing the drains, a cause of future waterlogging.

Hickson had envisaged Bradford RUFC to be in the making of Bradford FC as a club staging headline fixtures at Scholemoor as had been the case at Park Avenue in the 1880s, effectively offering alternative entertainment to that of Bradford City, Bradford Park Avenue or Bradford Northern. Instead the club became better known as somewhere to play Rugby Union rather than to watch and this was actually much closer to the early origins of Bradford FC prior to the mid-1870s when the onus had similarly been on participation.

In October, 1965 Scholemoor hosted a game with the Barbarians touring side to mark the 75th anniversary of its formation in Bradford and the centenary of Bradford Rugby the following year. Although the origins of Bradford FC could be traced to 1863, the date of formation has tended to be regarded as 1866 when affairs were organised on a more formal basis. The centenary reminded the club of its heritage and latterly it referred to itself as Bradford RFC, dropping the ‘U’ on the basis that it could claim ancestry as the oldest in Yorkshire. Bradford lost that game with the Barbarians 3-47 and were said to have been ‘punished but not disgraced’.

By the late 1960s there was a general consensus that the Scholemoor ground was no longer ideal for the club’s needs and its encouragement of participation in Rugby Union. This prompted consideration of options that included the first suggestion of merger with Bingley RUFC. In 1969 Bradford Corporation offered a site outside the city’s boundary between Thornbury / Pudsey (currently used by Bradford University sports teams). The move was rejected on the basis of being too distant [11] and after an aborted attempt to introduce greyhound racing at Lidget Green (that would have been unpalatable to Hickson), Bradford RUFC set about modernising its ground.

By the standards of professional football stadia, facilities at Scholemoor were modest although they were considered highly respectable in Rugby Union circles. The emphasis of investment in the ground was not on spectator facilities as opposed to amenities for members. The club had originally used a local school for changing rooms before erecting a large wooden hut of the type associated with Scout groups or church halls, eventually replaced in December, 1972 by a permanent structure. A clubhouse was constructed in the 1920s comprising bar and catering facilities as well as a meeting room, replaced in 1974 by a new structure that also included squash courts to capitalise on the popularity of the game at the time.

Scholemoor continued to host decent crowds. In December, 1972 for instance as many as 14,000 attended Lidget Green for the fixture between the NE Counties and New Zealand. It was also an attendance that compared favourably to any at Valley Parade or Park Avenue at that time.

In common with the three main football grounds in the city, the fate of Scholemoor was dictated by local authority planners and it became something of a pawn in the grand schemes of City Hall. At the beginning of the 1970s Bradford Corporation successfully opposed the introduction of greyhound racing and the cynic could be forgiven the suggestion that this served to keep its options open with regards the future use of the ground. In 1980 for example, it was reported that Bradford Metropolitan District Council investigated the possibility of Bradford Northern being relocated to allow Odsal to be divested for land-fill and waste disposal. Nothing came of this but after refusing planning permission for a Morrisons supermarket development, the council was able to make a discounted and uncontested bid for ownership in 1982. The subsequent reincarnation of Scholemoor as a civic sports centre in 1983 with an all-weather pitch (as well as the squash courts) most likely accomplished what had been on the planners’ agenda since the end of the 1960s. However, after a fanfare opening the centre eventually closed in 2000 and was left derelict for six years before community leaders reclaimed the site. Like Park Avenue, it was another tragic waste that insulted the efforts of Bradford’s sporting forebears such as Laurie Hickson.

When Bradford Rugby relocated to Wagon Lane in Cottingley to merge with Bingley RUFC in 1982 the club was already but a shadow of its former self. By the end of the 1970s it was struggling to recruit talented new players and handicapped by the fact that Rugby Union was still only played by three local schools – Bradford GS, Thornton GS and Woodhouse Grove. Whereas many rugby playing boys had traditionally returned to Bradford after university, often to join family businesses, this had become much less common. Another change was the relocation of many middle class families away from once affluent suburbs in Bradford to outlying areas that undermined the convenience or attraction of Scholemoor. By the time that professionalism was legalised by the Rugby Union in 1995 there was little prospect that Bradford & Bingley RFC – as a successor to the original Bradford FC – would become a leading side in the national game, something that would have pleased Hickson notwithstanding that the club was by now ranked among junior sides (the equivalent of a village team in the hierarchy of the late nineteenth century).

The Bradford & Bingley Sports grounds accommodate a first team rugby pitch, training fields and adjoining cricket pitch. It is home to a canoe club as well as Bingley Harriers AC. There is a degree of irony that Bradford CC abandoned Park Avenue in 1986, moving to Wagon Lane and merging with Bingley CC as cohabitants with the rugby club. Whilst Wagon Lane lacks the grandeur of the Victorian Park Avenue enclosure, in many ways the site in Bingley has much in common with what existed in Horton, fulfilling the original objective of a dedicated sports complex.

After conversion to an artificial football pitch in 1983, the Scholemoor site enjoyed a brief renaissance only to become derelict, latterly converted to an adventure playground. Had timing been different, Scholemoor could have provided a suitable home for Bradford Park Avenue as a non-league venue although the issue of vandalism would have remained a problem. Car parking would similarly have been difficult to accommodate and the congestion of Bradford’s ring road is now far worse, making access arguably more difficult than ever before.

Bradford Rugby never emulated Bradford FC and Rugby Union was not restored to prominence in the district as Hickson had hoped. Like Park Avenue, Scholemoor is testament to a lost dream, a monument to sporting ambition that succumbed both to economics – the forces of supply and demand that dictate financial viability and the means of existence – as well as local authority machinations. Just as at Park Avenue, the visitor to Scholemoor will detect few clues – the remnants of terracing aside – that it had been a football ground replete with a couple of grandstands.

By John Dewhirst

NOTES

[1] The early history of Bradford RFC is told on VINCIT Note that the Bradford Wanderers club which was the principal amateur side in the district at the turn of the centre had not been formed until 1899 (contrary to what has been written elsewhere).

[2] The circumstances of the Great Split of 1895 in Bradford is told on VINCIT

[3] The forgotten story of Shipley FC and the fate of other junior rugby sides feature on VINCIT

[4] LIFE AT THE TOP published by Bantamspast, 2016

[5] A series of open air boxing tournaments took place at Valley Parade in May, June and July, 1919.

[6] Rugby Reloaded podcast by Tony Collins

[7] It is quite conceivable that the misery inflicted by the Spanish flu pandemic in the final quarter of 1918 further contributed to this mood, one that could be could be described as an idealistic yearning for wholesome physical activity as a dividend of the peace. It is estimated that two hundred thousand Britons were killed by Spanish flu, roughly a third of the number of war fatalities.

[8] Prior reference by another writer to ‘Lidget Green’ as a sports venue refers to Horton Grange. Contrary to what has been written elsewhere the site at Scholemoor had not been used prior to 1919.

[9] The other venues included Newport, Swnsea, Inverleith, Portsmouth, Gloucester, Leicester and Twickenham.

[10] For further reading, refer: The King’s Cup 1919 – Rugby’s first ‘World Cup’ by Evans & Atkinson, St David’s Press (Cardiff) 2015. My thanks to Phil Atkinson, Editor of Touchlines (published by Rugby Memorabilia Society) magazine for letting me feature his scans of the programme cartoon and ticket as well as the photo of NZ v Australia at Scholemoor in 1919. Refer also to a feature on the World Rugby Museum blog.

[11] Of Bradford’s other surviving historic Rugby Union clubs, Baildon RUFC was formed in 1912 and Wibsey RUFC in 1932.

[12] My suspicion is that the enthusiasm for relocation was much greater on the part of Bradford Corporation than Bradford RFC with the former identifying the strategic value of Scholemoor for its own objectives. This is a theme to be the subject of a future feature on VINCIT.

[13] My thanks also to John Wright and Richard Lowther (Burglar Bill) for feedback.

The above menu provides links to other features about the early history of Bradford rugby, both amateur and professional.

=====================================================

The author has written widely about the history of Bradford City AFC. His books, ROOM AT THE TOP and LIFE AT THE TOP (pub bantamspast, 2016) narrate the origins of sport in Bradford, the development of sporting culture in the town in the nineteenth century and of how sport came to be commercialised. He provides the background to how Manningham FC and Bradford FC became established and of how they converted to professional soccer in the twentieth century as Bradford City and Bradford Park Avenue. These are possibly also the first business histories of nineteenth century rugby. John is currently working on a new history of the rivalry of the two sides as members of the Football League in WOOL CITY RIVALS (FALL FROM THE TOP).

His books form part of the BANTAMSPAST HISTORY REVISITED SERIES which seeks to offer a fresh interpretation of the history of sport in Bradford, addressing why events happened in the way that they did rather than simply stating what occurred (which is the characteristic of many sports histories).

Other online articles about Bradford sport by the same author

==================================

John contributes to the Bradford City match day programme and his features are also published on his blog Wool City Rivals where you can also find occasional Book Reviews

Tweets: @jpdewhirst

==================================

VINCIT provides an accessible go-to reference about all aspects of Bradford sport history and is neither code nor club specific. We encourage you to explore the site through the menu above.

Future articles are scheduled to feature boxing, cycling, football, the forgotten sports grounds of Bradford, the politics of Bradford sport and the history of Bradford sports journalists.

Contributions and feedback are welcome.