The forgotten story of the origins of football in Bradford and the significance of the junior clubs in the district…

What motivated me to write my books about the origins and development of sport in Bradford is the fact that there have been so many simplistic narratives about what happened. In the final quarter of the nineteenth century Bradford was known as a centre of sporting enthusiasm and a hotbed of rugby football with a vibrant network of clubs of different sizes. Yet surprisingly, coverage of their existence has previously amounted to little more than a passing footnote.

My interest in Shipley FC arose from wanting to discover more about a club that would have been my local side, playing opposite the Ring Of Bells public house. It reveals an alternate perspective to the history of rugby in the Bradford district and demonstrates that the story of how spectator sport developed in Bradford cannot be told with an exclusive focus on Bradford FC and Manningham FC alone.

Football supporters in Bradford have tended to ignore what happened before the formation of Bradford City AFC in 1903 despite the fact that the club had its origins as a rugby organisation. (NB Prior to World War One the term ‘football’ was synonymous with both rugby and soccer but in West Yorkshire it tended to mean rugby.)

Rugby League followers have similarly tended to overlook what happened prior to the launch of the Northern Union in 1895. Going further back you find common roots between rugby and cricket in Bradford.

The history of the origins of sport in Bradford and these common links has been ignored. Likewise the subtleties of what happened have been missed altogether and it is a subject area that has fallen foul of simplistic narratives. Surprisingly perhaps it has been overlooked that Bradford sport in the nineteenth century was heavily influenced by the military and motives of charitable giving. Sport was also recognised by our Victorian forebears as an important form of expression for civic pride and identity (or what was then described as local patriotism), another theme that has been forgotten despite its relevance for today.

Juniors rugby

Bradford is known as having been at the centre of the industrial revolution in the nineteenth century but it should also be recognised for a prominent role in the sporting revolution that took place in late Victorian Britain. In the 1880s the Bradford district derived a reputation as a hotbed of ‘football’, albeit the oval ball variety. The Association rules game was virtually unknown and attempts to promote it at Park Avenue in 1882 were thwarted by rugby enthusiasts whose sport claimed all available playing fields. To all intents and purposes, ‘soccer’ was crowded out until the end of the nineteenth century.

The introduction of the Yorkshire Challenge Cup competition in the 1877/78 season had been the catalyst for the spread of rugby and it was the triumph of Bradford FC in 1884 that gave added impetus to the enthusiasm. The competition captivated peoples’ imagination and the possibility of sporting glory inspired the emergence of new clubs whose numbers mushroomed in the wake of Bradford’s cup victory. The opening of Park Avenue in 1880 similarly had a big impact on local interest and the ground regularly hosted capacity crowds such that it was progressively enlarged during the decade. Football became a fashionable pastime among a broad cross-section of the population and so too it acquired a glamorous image with the stars – so-called ‘cracks’ – of Bradford FC being the celebrities of their era.

Further momentum was given to the game by the launch of the Bradford Charity Cup in the 1884/85 season. The trophy presented by Isaac Smith, Mayor of Bradford was known as the ‘small pot’ (the Yorkshire Cup was referred to as ‘t’owd pot’) and it became a focus for intense competition between junior clubs in the district. The Bradford Charity Cup gave a sense of purpose for smaller sides and a real opportunity for glory in a competition that remained fairly open; during the ten seasons of its existence between 1884/85 and 1893/94 there were seven different winners of the trophy and a total of ten different clubs reached the final.

Apart from the first two seasons when Manningham FC was allowed to enter its first team (and duly won the cup in each), the Bradford Charity Cup was confined to junior clubs in the Bradford district as well as the Bradford FC and Manningham ‘A’ sides (ie reserves). At its peak there were sixteen entrants with the final and semi-finals played at Park Avenue, the final at Easter weekend. The contribution of the competition to developing a localised football culture should not be under-estimated and it played a big role in sustaining support for junior rugby. Similarly, the manner in which it encouraged local sporting rivalries was a precursor to the impact of the Bradford & District Football League after 1899 and the Bradford Cricket League from 1903 which inherited the same passions.

By the end of the 1880s there was a defined hierarchy of clubs in what now constitutes the Bradford metropolitan district. At the top were the two senior clubs – Bradford FC and Manningham FC (who relocated to Valley Parade in 1886) – and then Bowling FC was acknowledged to be the nearest challenger below them. The next tier comprised around ten junior sides. Among the juniors, status was jealously guarded and whilst smaller clubs such as such as Bingley or Dudley Hill would typically play games with the Bradford and Manningham reserves, the likes of Cleckheaton and Bowling had higher aspirations and considered such fixtures infra dig. Among these clubs in particular a form of one-upmanship and proxy competition began to develop as they sought to upgrade their facilities.

At the bottom of the hierarchy were local clubs. These ranged from village sides such as Heaton FC (who had their own dedicated fields) to nursery clubs who were invariably based in local parks (Lister Park being a particular hub of activity).

A chain emerged whereby larger clubs would poach talented players from their smaller brethren who served as feeder clubs. A good example of this was the career of the celebrated full-back George Lorimer who died in 1897 at the height of his fame as full back for Manningham FC. Lorimer’s induction to rugby had been park football as a member of Manningham Free Wanderers in 1887 and he moved to Heaton FC and then Manningham Clarence before eventually joining Manningham FC in 1889. The flow of players was not one way and junior clubs also secured those who fell out of favour in the teams of seniors or preferred a less demanding routine.

Individuals could dream of upward mobility and the possibility of county or even international honours. However, it was the prospect of cup exploits that focused minds. Arguably, success in the Yorkshire Cup or for that matter, the Bradford Charity Cup became the raison d’etre of junior sides and provided the bravado to invest in grounds. It became a matter of pride among the respective organisations to boast a self-respecting home venue, fully enclosed and possessing a ‘grandstand’ (which was in practice an uncovered viewing platform). The actual financial commitment was modest but in emotional and relative terms it was not insignificant. Payment of annual rent was the principal liability of any club but it was the construction of grandstands and ground improvements, as well as maintenance, that dictated the economics.

A precarious existence

The finances of junior clubs could at best be described as precarious and considerable damage was inflicted by bad weather through postponements or from the expense of straw or oak husks to make a field playable. Invariably a glamour cup-tie or a big game with a local rival made the difference between profit and loss in a season’s workings. By the end of the 1880s financial reality had begun to catch up with these clubs who found themselves weighed down by indebtedness and increasingly desperate circumstances. The trade depression at the beginning of the following decade increased the difficulties further. Bradford Trinity, a club formed in 1880 – the same year as Manningham FC – decided to disband at the beginning of the 1894/95 season on account that the draw for the Yorkshire Challenge Cup had not afforded them a home tie.

The problems of the junior clubs were further exacerbated arising from their structures and weaknesses in financial management. As member organisations, subscribing members enjoyed the privilege of one man per vote but they were also equally liable for repayment of liabilities. Once a club found itself in difficulty there was little incentive for members to renew and as a consequence, financial difficulties were compounded by a drop in subscription revenue. All told, their structures impeded capital raising to fund losses and dissuaded people from getting involved who might have had the business skills to manage a club’s affairs. Not surprisingly it was not sustainable.

The loss of a ground arising from urban development was a factor that could crystallise the liabilities of a club and in this regard, Manningham Rangers is a good example. In September, 1891 for instance a benefit game had to be organised at Valley Parade to raise funds for Manningham Rangers to repay its liabilities prior to dissolution after its Oak Lane ground (roughly bordered by what is now Dartmouth Terrace and Garfield Avenue) was requisitioned for building. Formed in 1882 Manningham Rangers was a classic case of a club that had been formed in the heat of enthusiasm for rugby in Bradford. In 1884 its membership was reported to have been 55 and at the club’s AGM the same year it reported its expenditure to ‘have been rather heavy’ which had presumably related to the expense of ground development and maintenance.

Manningham Rangers became a feeder to Manningham FC (which afforded it the occasional use of Valley Parade) and a number of its players including Alf Barraclough and Ike Newton graduated to the senior Manningham side. On the other hand, the half-back Arthur Briggs – nicknamed ‘Spafter’ – was acclaimed as the successor to Fred Bonsor at Park Avenue after moving from Manningham Rangers via Bowling Old Lane.

By the start of the 1890s most junior clubs were struggling to remain solvent and the looming issue of broken time payments had grave implications for their finances. Although sympathetic to the needs of individual players, few clubs could afford to pay generous expenses. In 1894 the secretary of Bowling FC was realistic in his assessment that professionalism was an inevitable outcome for northern rugby. Nonetheless he had grave misgivings about how clubs such as his own could accommodate on a widespread basis even the intermediary measure of just broken time payments. The likes of Bowling FC were all too mindful of the delicate balancing act that they already faced between financial failure and survival; the fear was that legalisation of broken time monies would expose junior clubs to an auction for talent in which they could not compete.

The winding-up and disappearance of countless junior sides across Yorkshire and Lancashire by the end of the decade was as dramatic as their sudden emergence in the 1880s. If previously their financial difficulties had been overcome by arranging a fixtures with a local senior side, by 1900 the reality was that rugby football no longer had the same appeal and the leading Northern Union clubs had their own problems. Neither was it feasible for the Northern Union to repay the debts of the juniors and they were to all intents and purposes left to their fate, described by the Yorkshire Post of 12th February, 1900 as a consequence of their ‘overweening ambitions’.

The example of Heaton FC

Heaton FC was a good example of a club that over-committed itself in chasing a dream – it was a shooting star that fell to earth in little more than seven years. Established in January, 1884 the club had an impressive rise that was propelled by enthusiasm and ambition in equal measure. Its original name – Heaton Cricket & Football Club – hints that it may have started life as an offshoot of the parent cricket club. Yet by April, 1891 it was on its last legs, the first of many junior clubs who disappeared in that decade almost as quickly as they had emerged in the 1880s.

(NB Although the Heaton club played according to Rugby Union rules and was, to all intents and purposes, a rugby club it was common practice in West Yorkshire at the time to be known as a football club and the term ‘football’ is best interpreted in the generic sense rather than code specific.)

In the 1885/86 season Heaton FC was one of the sixteen clubs invited to compete in the Bradford Charity Cup which was confirmation that it was regarded as one of the stronger sides in the district. Indeed the proof of its credentials was demonstrated by reaching the second round where it was defeated by the Bradford ‘A’ team. That particular tie in December, 1885 was played in front of three thousand spectators at Park Avenue and provided a taste of the big time for a village club formed less than two years previously.

Heaton FC had its headquarters at the King’s Arms – less than half a mile apart from the Fountain Inn which was later adopted by Manningham Rangers. Its home venue was originally the Heaton recreation ground adjacent to the cemetery but a creditable record in the Bradford Charity Cup fuelled the confidence of members and encouraged the search for a new ground. In 1887 Heaton FC secured a field off Emm Lane – most likely the site of the St Bede’s playing fields – and its first game there in August, 1887 was commemorated with an exhibition match against a Manningham XV.

The year 1887 was probably the peak of football fever in Bradford and a measure of this was the launch by The Yorkshireman magazine of a dedicated football publication in September. It seemed that there was a contagious enthusiasm to commit monies in the pursuit of sporting glory. Heaton FC was not the only club investing in a new ground. So too the Bowling Old Lane football ground opened the same weekend as that at Emm Lane. Similarly, Shipley FC announced in August that it had invested £80 improving its ground opposite the Ring of Bells. Earlier, in March there had been the controversy of a postponed cup tie at Park Avenue which defined the future relationship between the Bradford and Manningham clubs. The affair arguably reflected badly upon the game, inviting ridicule that a sporting dispute should be referred to the Crown Court. The respectability of (rugby) football was to be further tested in relation to the financial viability of its also-ran clubs – the headline profitability of Bradford FC would be proven to be the exception as opposed to the rule.

The calibre of Heaton FC was confirmed by victory over the Bradford ‘A’ team in December, 1887 and in March, 1888 the Heaton side was defeated in the semi-final of the Bradford Charity Cup by Cleckheaton, a poorly attended game at Park Avenue. The achievement proved to be the apogee for Heaton FC and three years later the club disbanded, having struggled to service its debts. The expense of the new ground had undermined its prospects of survival and in the end it was forced to rely upon the goodwill of other clubs to pay its liabilities. Fund raising efforts for this purpose included a testimonial played on behalf of Heaton FC at Valley Parade in April, 1891.

Ironically Heaton FC achieved a creditable record in the development of young players but this served only for it to become a de facto nursery side for Manningham FC rather than for its own benefit. George Lorimer was one such player who graduated to Valley Parade via Manningham Clarence in 1889 where he became established as one of the best full-backs of his era. Another former player, Horace Duckett represented England in 1893 whilst a Bradford FC player.

The case of Shipley FC

Shipley is a town to the north of Bradford whose growth in the nineteenth century was similarly driven by the textiles industry. With a population of around 20,000 in 1890, it was roughly an eighth of the size of its larger neighbour.

Shipley FC provides an interesting case study of the fate of junior clubs and their experience after the split in English rugby in 1895. Shipley FC was better placed than many others to survive. Although traditionally ranked as a third tier club, it had the potential benefit of a decent local catchment with a strong local identity.

The club was also one of longest established in the Bradford area. The formation of Shipley FC in 1876 was at the same time as that of Bingley FC and Keighley FC – evidence that football mania had spread down the Aire valley and of a parochial instinct to keep up with neighbouring towns. Shipley FC had a relatively modest existence and in its early years, highlights of a season tended to be its games with near neighbours Saltaire FC (formed 1883, originally known as Saltaire Trinity) and Windhill FC (formed in 1884).

There is an argument that the potential of Shipley FC was limited by a combination of (a) the Saltaire and Windhill clubs being in close proximity as well as the fact that (b) its ground opposite the Ring of Bells was relatively peripheral to the centre of town and areas of residence. That said, rugby in Shipley – as in nearby Bradford – was shaped by urban geography and other than at Baildon Bridge there were few options for a ground that could have provided a central catchment. Just as the emergence of Manningham FC met the demand for a local club that was conveniently located, so too we can assume the same impulse behind the formation of the Saltaire and Windhill clubs. Ultimately however, the prospect of Shipley establishing itself as a senior club was limited by the fact that Manningham FC was on its doorstep and easily reachable by train.

Shipley FC similarly had a close rivalry with Bingley FC and Keighley FC. That with Bingley was impacted by an incident in a Bradford Charity Cup tie at Valley Parade in 1886 when a disputed winning try led to the Bingley players leaving the field three minutes before the end of the game. It was not unique to Shipley that by the end of the 1880s local football had established its own folklore and countless legends of petty grievances that sustained public interest.

During the first half of the 1880s Shipley FC began to derive kudos from the graduation of its players to one of the seniors – either Bradford FC or Manningham FC. In common with other clubs of similar stature there was genuine pride when former Shipley men made the grade at a higher level. (NB In the Bradford district there was a sense of patriotic duty for a player to represent the town club, Bradford FC.) In common with other junior sides, Shipley FC became a feeder to the nearby senior clubs with a number of its players graduating to both Bradford FC and Manningham FC. At the beginning of the 1884/85 season for example a couple of Shipley players were enticed to join Manningham FC, by this stage emerging as a serious challenger to Bradford FC.

Shipley FC 1886/87: Back row, left to right: A Thornton, H Shaw, J Moore, C Brumfit, H Walker, W Woodward, and F Hanson (umpire). Middle row, left to right: S Holmes, S Hodgson, J Dawson (captain), J Hartley, J Hardaker, and Lister Wade. Front row, left to right: James Wade, T Horsfall, G Bateson and C Bailey.

In October, 1886, Shipley FC was able to boast that one of its men – Charles Brumfitt – had graduated to Park Avenue to become a member of the town’s premier side. Sadly, things did not work out and he returned to Shipley FC a few weeks later. Newspaper reports suggested that he had been excluded from the Bradford FC team on account of favouritism. Nonetheless, Brumfitt did not suffer from his association with Bradford and he represented Yorkshire in 1887 as a Shipley player.

Shipley FC cup record

The Athletic News of 12 October, 1886 described Shipley FC as a ‘coming’ club… ‘a much smarter lot than many people think’ and this reputation appears to have been sufficient to attract Widnes to Shipley in December, 1887 for a game on their Yorkshire tour. However, until the formation of a league competition in 1892, Shipley’s ranking in Yorkshire rugby was judged on its performance in the Yorkshire Challenge Cup and in that regard, it had a mediocre record. The club’s entry to the cup for the first time in the 1881/82 season arose from the withdrawal of higher profile pedigree sides and hence there was no surprise when Shipley FC was knocked out in the opening round. Between 1882 and 1895 the club never progressed beyond the second round. A consequence of this was that the Yorkshire Cup was never a money-spinner for Shipley FC and it never had the luck of a lucrative home tie. In March, 1893 for example the first round home tie with Armley generated gate money of only £24 (with a corresponding crowd of just under two thousand) and the second round tie that season was unlikely to have attracted an attendance in excess of four thousand.

A particular bogey team in the Yorkshire Cup was Dudley Hill who defeated Shipley twice, in 1883/84 and then 1886/87. Nevertheless, Shipley enjoyed a couple of glamour ties: in March, 1892 the team was defeated in the first round by near neighbours Manningham at Valley Parade and then in March, 1895 it suffered an opening round defeat at the cup holders Halifax.

Shipley FC was also involved in a couple of controversial cup ties, the circumstances of which provide a fascinating insight into the Victorian game. In March, 1893 Shipley had played Wortley at home in the second round, at stake a third round tie at Otley. Wortley managed a narrow victory but Shipley contested the result when it became known that the Wortley side had included a couple of Wakefield men. The tie was ordered to be replayed, on this occasion at Valley Parade but once again Wortley emerged as victors.

The following season, Shipley FC was defeated in the first round by Hull KR. On this occasion it was controversy about a drunken referee that led the tie to be replayed. The Hull Daily Mail of 20 March, 1894 was circumspect in describing the ‘allegations against the referee‘ that led to the cup tie being restaged despite the Hull side having defeated Shipley, 7-0. It was alleged that George Bateson, the Shipley captain had drawn attention to the ‘referee’s condition’ and that he did not think he was in a fit condition to act as referee – during the course of the game ‘decisions were given that were not in accordance with the rules.’ One of the Hull KR supporters protested that the referee, Mr C. Berry was perfectly sober before the start of the game but being of a ‘free and easy disposition’ it gave the Shipley players the wrong impression of his condition! The Yorkshire Rugby Union ordered that the game should be replayed at Castleford and Hull KR won that game, 14-0.

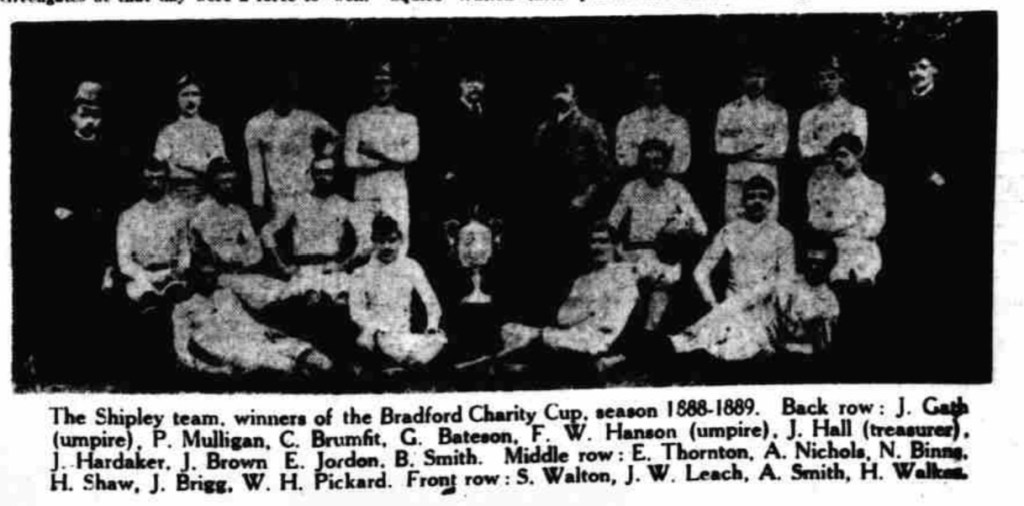

Shipley FC had the best record of all clubs in the Bradford Charity Cup and its achievements in the competition represented the only honours credited to the club prior to 1895. Shipley were losing finalists in 1886/87 and then winners in successive seasons, 1888/89 and 1889/90. On both occasions Shipley defeated Buttershaw in the final although in 1890 had been scheduled to play Manningham ‘A’. Buttershaw had previously won the cup in 1888 and stood in when the Manningham team was unable to participate due to being on tour in South Wales.

Possibly the largest crowd for a game involving Shipley FC was the Bradford Charity Cup final of 1886/87 against Cleckheaton that was attended by twelve thousand. Also at Park Avenue, the attendance for the final in 1889 was reported to have been eight thousand and the semi-final against Bowling Old Lane in 1890 attracted seven thousand. However, by virtue perhaps of the final in 1890 being something of an exhibition game, the crowd was said to have been only three thousand. The celebrations that followed victory at Park Avenue on Easter Monday, 1890 were recorded in the Shipley Times and confirmed the enthusiasm for the competition. It was said that the victors were brought back to Shipley in an open waggonnette and the successful players were greeted by the Saltaire Brass Brand and excursionists enjoying the Easter holiday at Shipley Glen, a local beauty spot.

Unfortunately the club’s record in the Bradford Charity Cup was overshadowed by the death of Lister Wade as a consequence of injuries sustained during the course of the semi-final tie with Saltaire FC at Park Avenue in March, 1889. The Bradford Daily Telegraph of 9 March reported that several rough incidents had occurred in the second half of the game and that he had been ‘recklessly charged by two opponents’ and forced to leave the field with ‘bleeding from the ears’. Yorkshire rugby had become associated with violent play and the incident was widely reported throughout Britain in syndicated despatches that gave further credence to the sport’s critics.

At the end of November, 1889 a Shipley player, George Flaxington broke his leg in the first round Bradford Charity Cup tie with Manningham Rangers. The North Eastern Gazette of 2 December, 1889 reported that ‘Being a cup tie encounter, there was a good deal of excitement and some rough play.’ Commenting on the incidence of violence, the observation was made at the club’s AGM in June 1890 that ‘Betting was responsible for a good many injuries, as it often happened that a player who had made a bet of 2s., and thought he was going to lose it, would half kick a man to death rather than lose.’ (Reported in the Shipley Times of 28 June, 1890.)

The finances

In 1884/85 Shipley FC reported income of £97 and in 1886/87 it was £136; by 1889/90 this had increased to £263. With limited cost commitments in 1884/85 and 1886/87, the club was also able to boast decent operating surpluses of £20 and £15 respectively. In 1889/90 the operating surplus was only £3, a consequence of the significant increase in expenses.

The earlier profitability of Shipley FC encouraged investment in its ground and at the club’s AGM in 1887 it was said that ‘a great many improvements for the convenience of spectators in the field were contemplated, and would no doubt be carried out during the summer months‘ (as quoted in the Bradford Observer of 4 May, 1887). Accordingly, the wooden grandstand constructed on its ground opposite the Ring of Bells may have dated from then with the timing of the investment prompted by the decision of rivals Windhill FC who had committed to spending £100 on developing a new ground in the same year. (This was a major commitment for Windhill FC because in 1887/88 its gate receipts amounted to only £57 and in May, 1888 the Windhill members faced a situation where £20 of club funds was unaccounted for and the cash book was missing.)

The growing stature of the club may be gauged from the growth in turnover: revenues of £263 in 1889/90 were hardly insubstantial in the context of average weekly earnings of around £1. Nevertheless, when measured in financial terms, Shipley FC was a relative minnow compared to the likes of Bradford FC or Manningham FC whose revenues that season were £3,420 and £942 respectively. Despite the higher income, it is striking that in 1889/90 the operating surplus of Shipley FC was only £3, evidence of a finely balanced if not precarious existence. New monies were being absorbed almost as quickly as they were being earned and with minimal reserves it only took a match postponement to instigate a financial crisis.

The increase in operating costs was accounted for by the expense of rail fares, playing kit, print costs and advertising as well as straw (to protect the field). The comments of the Shipley chairman at the AGM, quoted in the Shipley Times of 28 June, 1890 reveal the burden of travel costs, considered unavoidable for an ambitious club: ‘The committee was endeavouring to reduce the expenses but considering the gates, the railway fares were enormous. He had brought the matter up before, and he thought that if they got fixtures nearer home it would be to their advantage, although the prestige of the club should not be sacrificed to save a few shillings.‘ It was also revealed that the squad comprised just 15 players, two reserve men, two trainers, an umpire and an officer. ‘A good deal of money was paid for men coming from Idle, Tong Park and Manningham while training. These men came down three or four times a week, when there fares would amount to 1/6 or 2s. The railway fares last year were £63 but they did not go to West Hartlepool or Askam.’

Other items of expenditure would have been directly related to the players themselves, classified innocuously as ‘refreshments’ but quite possibly including illicit boot money (the term applied to covert monetary rewards, literally dropped into players’ boots). In 1889/90 the annual rent charge was reported to have been £11 and further expense would have derived from the upkeep and improvement of the ground as well as repayment of debt relating to ground development.

A local institution

By the start of the 1890s Shipley FC was well-established in its community. The Shipley team comprised men who were motivated to play for local honour and the relative lack of honours should not be interpreted as lack of passion or commitment. Furthermore, reported crowds of around two thousand for holiday fixtures reveal the interest of local people in the club’s affairs. Involvement with the club also afforded a degree of social prominence that was not restricted to the players themselves.

Responsibility for managing the club’s affairs bestowed status on committee members. One person who became involved was Maurice Bonsor who lived nearby at Hall Royd in Shipley and in 1892 he was elected president of Shipley FC. The Bonsor family (which was of French descent) had settled in Shipley and the father, Robert was a textiles dyer. Maurice is better known for having been the brother of England international and Bradford FC captain Fred Bonsor (who guested for Saltaire FC in December, 1891 against Shipley). Nevertheless, he had a respectable record in his own right as a local sportsman.

In 1881 Maurice had joined Bradford Trinity and was latterly captain of the second team before he joined Bradford FC. Between 1883 and 1887 he was an irregular member of the first team at Park Avenue and he remained an active squad player prior to his retirement from the game in1890. Maurice was also a captain in the Rifle Volunteers and as a keen cyclist was responsible for organising a ‘Cyclist Section’ within the Bradford corps. Fred enjoyed celebrity status in Bradford and there is the sense that Maurice’s patronage of Shipley FC was his way of defining a reputation and legacy. Indeed, the egos and vanity of committee members was a major factor in driving the development of individual rugby clubs.

Nevertheless, as financial commitments increased and football clubs began to accrue liabilities, the responsibility of office brought with it the personal risk of having to repay debts in the event of winding-up. The issue weighed on peoples’ minds and would later deter individuals from seeking election to Shipley’s leadership committee. The same consideration may have dissuaded Bonsor from maintaining his involvement with the club.

Shipley FC at the time of the rugby split in 1895

In 1892 Shipley joined the third tier of the new Yorkshire league competition. In the last season under the auspices of the Yorkshire RFU a total of 64 clubs comprised the four divisions, of which 14 were from the Bradford district listed as follows: Seniors in the top tier: Bradford FC and Manningham FC; second tier: Bowling FC; third tier: Bowling Old Lane, Keighley and Shipley; fourth tier: Bingley, Brownroyd Recreation, Idle, Low Moor St Mark’s, Saltaire, Silsden, Wibsey and Windhill.

Newspaper reports confirm that league games were highly competitive. Yet the sporting world inhabited by Shipley FC seems quaint in contrast to what we are familiar with. A wonderful illustration of the practical differences between then and now is provided by the Shipley correspondent of the Yorkshire Evening Post on 29 January, 1894: ‘There was a singular misapprehension at Shipley, on Saturday, as to the result of the football match between the Hull Kingston Rovers and Shipley, and apparently it was due to the referee getting bewildered by the storm. The spectators on both sides believed the result to be a draw, but as they were leaving the field a question to the referee elicited the response that Shipley were the winners with 8 points to 6. Further inquiries, however, showed that the storm had played havoc with the referee’s pencillings, and he had concluded that the Shipley men were entitled to a goal from a try, and not a penalty goal. The point was, however, really a penalty goal and the match was a draw after all. Owing to the storm, good football was out of the question, and Shipley were disappointed in not winning.’

Around the time of the split in 1895 Shipley FC was struggling to make ends meet and was faced with servicing debts that had built up from the costs of ground development as well as the funding of trading losses. It was hardly a unique state of affairs and the trade depression at the turn of the decade was blamed for having exacerbated the financial difficulties of most clubs in the Bradford area (by virtue of impact on disposable incomes). In December, 1894 the prospective Unionist MP for Shipley, Fortescue Flannery had encouraged the three Shipley-based clubs – Saltaire, Shipley and Windhill – to combine.

The Leeds Mercury of 5 December, 1894 quoted Flannery who had ‘suggested that if the three clubs amalgamated they could get a team which would carry them to the front rank of football clubs in Yorkshire.‘ Windhill FC had been runners-up in the Bradford Charity Cup in 1892 and 1894 – an achievement that may have fostered unrealistic expectations – and its membership could not be persuaded to give up independence or abandon the Crag End ground. Merger discussions continued between Saltaire and Shipley although these were reported to have been aborted in March, 1895 on account of the Saltaire club’s objections to playing at Shipley’s ground. However whilst amalgamation made sense, the obstacles were more than just emotional. A combined club for instance still faced the obligation to repay the collective debts and few members would have relished inheriting the liabilities of rival clubs in addition to their own.

Increasingly, Shipley FC came to rely upon fund raising social events to remain viable. During the 1896/97 and 1897/98 seasons the Ring of Bells ground also hosted the newly formed Shipley AFC which may have been a further attempt to generate additional income. The side was one of few playing the association code in the Bradford area at the time but became defunct before the launch of the Bradford & District FA which boosted the game after 1899. Arguably the soccer initiative was premature and the Shipley club might otherwise have established itself as a leading pioneer of the game. (The town never had a soccer club of any stature; although a revived Shipley AFC emerged in 1900 and joined the Bradford & District FA in 1901, it disbanded in 1920 on account of indebtedness.)

A new opportunity for Shipley

The new Northern Union competition that came into being at the end of August, 1895 was not universally popular in the north and certainly not in the Bradford district. Criticism of the breakaway came from those who looked upon it as a de facto cartel, dismissive of the interests of smaller clubs such as Shipley. The breakaway was viewed with a high degree of cynicism and the Shipley committee identified an opportunity for the club to attract people who were alienated by the decision of the seniors to secede from the Rugby Union.

The formation of the Northern Union gave Shipley a new lease of life and the possibility of defining for itself a new niche as the leading side in the district among those remaining within the Rugby Union. In the absence of the seniors, clubs such as Shipley viewed the breakaway of the rebels as an opportunity to grab the limelight as well as a means of financial salvation.

Optimism was raised by the defection of prominent players from Bradford FC. For example, James Barron and Harold Ramsden joined Bingley FC with whom they later obtained England caps and the Shipley FC team was strengthened by the return of Yorkshire county player Herbert Ward (see Baines card above). Similarly, Frank Murgatroyd re-joined Idle FC and Arthur Briggs opted to join Pudsey. These players wanted to avoid the prospect of being ‘professionalised’ by playing Northern Union football at Park Avenue and by returning to their local clubs believed that they would avoid compromising their chances of county and national selection.

The Shipley team was further strengthened by the inclusion of Charles Emmott (pictured), a former England international half-back (capped once in 1892 against Wales) and Yorkshire county player (for whom he made four appearances between 1890/91 and 1891/92) whilst with Bradford FC. Emmott was a Saltaire man and had played with his local club after making his debut in 1885. In September, 1890 he had transferred to Park Avenue before returning to Saltaire FC at the start of the 1892/93 season. He then had another brief spell with Bradford FC in 1893/94, signed by that club in September, 1893 as an emergency response to the team’s loss of form but re-joined Saltaire once again before moving to Bowling FC midway through the 1894/95 season. As an established joiner by trade, Emmott would not have been concerned with receipt of broken time payments and his transfer to Shipley FC in September, 1895 (at the age of 26 years) was presumably with the intent of remaining an amateur and reviving his county career. He remained with the club until January, 1901, ending his playing days with Windhill FC. In 1904 he was appointed trainer of Bradford Wanderers RUFC who were based at Red Beck Fields, Shipley.

At the end of the 1895/96 season Shipley FC finished as champions of the new second tier league of the Yorkshire Rugby Union whilst neighbours Idle FC finished top of the third tier.

During the following season, 1896/97 Shipley FC established itself as the top amateur side in the district and its members had genuine ambitions about the club reaching the heights of English rugby.

In 1896/97 Shipley FC were beaten finalists in the Yorkshire Cup, losing to Hull KR. Despite the competition being much diminished in the absence of senior clubs, the achievement fuelled the improbable dream that the club could transform itself and become one of the leading sides in the country. It was claimed that the occasion of the final was the first in 18 years to suffer rainfall but this was no excuse for a gate described as one of ‘meagre dimensions’.

Even so, Shipley FC appears to have benefited from higher attendances after 1895. On the same day in October, 1896 for example there were three thousand spectators at Shipley to witness the game with Featherstone and only five thousand at Park Avenue to watch Bradford FC and Liversedge. On 22 January, 1898 the Yorkshire Evening Post ventured that Shipley FC had had a record gate for the visit of Keighley with receipts in excess of £80: ‘It has often been remarked that gates in Bradford are not now what they were in former times. One explanation of this is to be found in the rise of clubs like Shipley, Bingley, and Keighley. Many enthusiasts from the Airedale district used to go to Park Avenue and Valley Parade not long ago for their football. They now find a sufficient attraction nearer home.’ The crowd at the Ring of Bells ground on that occasion must have been close to six thousand.

The following season Shipley were winners of the first division, ahead of local rivals Keighley who were runners-up and Bingley who managed only to avoid the wooden spoon. Nevertheless, the mood of optimism and confidence was tempered by financial worries. The Shipley Times of 18 March, 1899 reported the dinner in ‘celebration of their having carried off the premier honours of the Yorkshire No.1 Competition.’ The chairman had congratulated the club but ‘wished to see the club occupying an even better position, and if its supporters only pulled themselves together and wiped off the debt which a present hampered it he had no doubt they would succeed, and he need not say they would be chary of contracting similar debts in future.’ Another official was quoted to the extent that ‘every year Shipley were getting nearer to the top of the tree in matters of football so far as Yorkshire was concerned, and their efforts during the present season, taken on their merits, were not only a credit to the players and the committee, but to the town.’

The collapse of a dream

The immediate aftermath of the split in 1895 had revealed the interdependence of the senior and junior clubs and both groups became losers. For the latter, the RFU ban on relations with the Northern Union took away an umbilical cord. The seniors were also impacted by new complications about recruiting local talent from sides whom they had always considered de facto nurseries. For the players, graduation to one of the senior clubs was now a make or break affair. Having represented a senior club or even played a trial game with a Northern Union side, the individual concerned ‘professionalised himself’ and by being denied amateur status was thus prevented from ever playing with a junior club under the auspices of the Yorkshire Rugby Union. In other words, where previously there had been a food chain between the small and large clubs as well as the backflow from senior to junior clubs, the free movement was now restricted in one direction only.

In 1897 Shipley FC was reminded of its relative status in the rugby world with the defection of Nim Greenwood to Manningham FC. Greenwood (pictured) had been one of the club’s leading players and a member of the cup team defeated by Hull KR in the Yorkshire Cup final. His loss was a major blow to Shipley and demonstrated that the Northern Union would always be a magnet for leading players in the Yorkshire Rugby Union. (He is remembered as one of the best of his era and after five years at Valley Parade joined Pontefact before transferring to Bradford FC in the second half of the 1903/04 season. Greenwood was in the Bradford team during the final season of rugby at Park Avenue in 1906/07 and in 1906 was a member of the club’s Northern Union Challenge Cup winning team.)

The problem that the junior clubs faced was that they were forbidden to play fixtures with sides who had joined the Northern Union. At a stroke this removed the financial benefit of prestige games, in particular cup ties. Similarly, Bradford FC and Manningham FC had previously taken it upon themselves to organise friendlies with struggling junior sides to sustain their finances but this charity was no longer possible.

Before long there began to be misgivings in Yorkshire about whether the traditional junior clubs could survive as members of the Rugby Union in parallel to the Northern Union. The impasse between the RFU and Northern Union offered little prospect for junior clubs to resolve their financial difficulties. If anything, the pressures increased as a consequence of being forced to travel longer distances to secure fixtures and being unable to attract the public to games involving mediocre or nondescript opposition. In 1897 there was even talk of establishing a new, separate union of those clubs to represent their interests and this was prompted by charges of professionalism against Hull KR which most observers considered unfair. The subsequent defection of Hull KR to the Northern Union was generally interpreted to have dealt a blow to a third way solution and forced a binary choice. With the benefit of hindsight, the move by Hull KR was highly significant in determining the fate of those left behind as members of the Yorkshire Rugby Union.

The timing was cruel for Shipley FC which could rightfully consider that it had the opportunity to make a name for itself in Yorkshire rugby. Even if the competitions were weakened as a result of defection to the Northern Union, Shipley FC could still boast having been a finalist in the Yorkshire Challenge Cup of the1896/97 season and in 1898/99 champions of the top tier of the Yorkshire Senior Competition. It was confirmation to partisan supporters that Shipley FC was on the verge of a breakthrough and therefore it must have seemed almost as if a rug was being pulled from under its feet as one by one, other junior clubs either fell by the wayside or opted to join the Northern Union. For Shipley FC, the dream ended no sooner than it had begun.

Shipley FC and the Northern Union

Despite the depletion of the Yorkshire Rugby Union, and with it the loss of critical mass, there was still guarded optimism among the membership of Shipley FC. In 1896/97 the cup run had helped Shipley to generate record receipts of £364, albeit with an operating surplus of only £1. The following season, income fell by 7% but remained at a respectable level by historic standards. Even though there was a profit of only £3, the financial outlook was not critical and at that stage it could not be said that the club was disadvantaged by its membership of the Yorkshire Rugby Union.

The disbanding of Saltaire FC also presented an opportunity. Shipley FC inherited its wooden grandstand which was removed from Saltaire’s ground off Albert Road and it was also able to call upon the support of its former rival. It led the Leeds Times of 10 September, 1898 to suggest that the club’s position this season ‘will be strengthened by the recent demise of the Saltaire organisation.’

Shipley became known as a club that was loyal to the Yorkshire Rugby Union, dismissive about joining the Northern Union. A good reason for this was that Shipley FC had established itself as one of the leading clubs and enjoyed a status that had previously been denied. The Shipley Times report of the Shipley FC AGM of 18 August, 1898 confirmed that ‘the chief reason for remaining in the Yorkshire Union was that if Shipley FC joined the Northern Union they would have no chance of getting a player into the county, they would have no representation, and they had no guarantee of promotion by merit. Seeing that the club had now got to the top of the ladder in Yorkshire amateur football as it existed, he thought the best thing they could do was to remain loyal to the English Union.’

Although there remained a degree of bitterness towards the original rebels it was telling that there was a softening of attitude towards the Northern Union. At the same meeting, the chairman acknowledged that ‘at one time he did not think much of the tactics of that organisation, but to his mind they were in a vastly different position to what they were when they left the Yorkshire Union. They now had open professionalism and promotion by merit, and their action was now altogether open and above board.’ He added that the best thing they could do was forming another union of their own, an option discussed among other Yorkshire clubs the previous year prior to the defection of Hull KR. In other words, far from considering the Yorkshire Rugby Union to be ideal it was viewed as a ‘least worst’ option and a comfort blanket that afforded familiarity.

It was not an exaggeration to say the viability of junior clubs was questionable. Shipley FC was no exception to this but unlike many others it had the good fortune for its bank borrowings to be guaranteed by a benefactor. Percy Illingworth was another man of means to be involved with the club, the youngest son of the Bradford industrialist Henry Illingworth. Percy boasted a creditable football pedigree having represented Cambridge University, Blackheath and, as a guest player, Bradford FC. It is my belief that he – and possibly Maurice Bonsor – had encouraged the club’s ambitions to become a leading side within the Rugby Union after 1895. Illingworth’s motive to guarantee the bank borrowings in 1899 might even have been to discourage Shipley FC from joining the Northern Union. Yet even though Illingworth provided support he could hardly be described as a sugar daddy who was prepared to underwrite losses indefinitely and at the AGM in August, 1899 it was reported that his guarantee was limited to £40, only a third of the total debt at that time.

(Like Maurice and Fred Bonsor, Percy Illingworth was another prominent Bradford football personality who served in the South African war between 1899-00. Had Illingworth been actively involved with Shipley FC affairs in the 1899 close season then quite possibly he may have persuaded the club to remain in the Rugby Union.)

Loyalty to the Yorkshire Rugby Union was inevitably tested at the end of the 1898/99 season when, despite winning the first division of the Yorkshire RFU competition, there was a 30% collapse in gate receipts. It left no room for sentimentality and members were more concerned about facing personal liability for the club’s growing indebtedness. Not everyone was in favour of the club joining the Northern Union and it was a contentious issue that divided opinion. The collapse of cricket leagues in Yorkshire in 1899 and scepticism about the sustainability of competitive leagues had even led some to question whether the Northern Union had a future. There was an impasse between different factions which was not surprising given what was at stake and the sheer uncertainty of outcomes. It must have felt like a jump into the unknown, a bet on the future of the club.

The Shipley Times of 18 March 1899 reported a meeting of members: ‘The chairman appealed for help in the endeavour which the club were making to free themselves from the debt which had hung like a millstone round their necks for many years. If they could not wipe out that debt now, when the club was practically at the zenith of its fame, he did not know when they would be able to do it… there was no denying that the gates had not come up to expectations.’ With regards the Northern Union, the chairman said ‘they had thrashed the matter out time after time and he did not think the situation had altered. The club was better off without it. They were not governed by the rod of iron which dominated the operations of many of the clubs in the Northern Union – some of which he knew would be only too glad to return to the Rugby Union.‘

The Shipley FC AGM was delayed until the summer, most likely on account of the politics between different member factions. In the meantime, local rivals, Windhill FC – the ‘Crag Enders‘ – seceded immediately after the end of the 1898/99 season but what is intriguing is that that club attempted to rename itself ‘Shipley’ as a Northern Union club. I find it difficult to believe that this initiative was entirely unrelated to the disagreements that were ongoing between members of Shipley FC. Yet whether it was a case of mischief or commercial opportunism, Windhill FC sought to position itself as the Shipley representative in the Northern Union with the intention to rename the club ‘Shipley Northern Union FC’.

The move constituted a threat to Shipley FC with the implication of local players and even spectators being attracted to Windhill at the expense of the former. The Yorkshire committee of the Northern Union pre-empted this but it was not until the beginning of September, 1899 that it refused to grant authority for the name change. Agreement already existed between the Northern Union and the Football Association to prevent duplicate names but the Windhill case represented a rare example of co-operation with the Yorkshire Rugby Union to prevent an identity clash.

The Shipley Times report of 9 August, 1899 spoke of the heated debate when the AGM of Shipley members eventually took place: ‘some members expressed dissatisfaction at the manner in which the club had been worked during the last season. The question of old liabilities continually cropped up, and mainly on account of being held responsible for the debts, most of the late officers were unwilling to be re-elected. There was a stalemate in terms of future options although joining the Northern Union was rejected. It was agreed that the old committee would meet to determine a course of action for the forthcoming season.’

The reluctance of people to accept office on account of the club’s liabilities led to the old committee being asked to resolve the deadlock and a final decision was made three weeks later on 30 August to join the Northern Union. The decision was made at roughly the same time as the conclusion of the Windhill renaming saga which must have had a bearing on the outcome. Ultimately, the fact that defection took place in the last week of August, close to the beginning of the 1899/00 season suggests that it was not well-planned.

There were two key reasons cited in the Leeds Mercury of 2 September, 1899 for the decision. The first was a dearth of fixtures with the few arranged being far below the standard of prior years and only 16 games having been scheduled for the forthcoming season. The second was that the club had to face the probability of having their ranks considerably weakened by the migration of their players to wealthier Northern Union clubs. The defection of two leading players at the end of August, 1899 may have prompted the decision to secede to the Northern Union with Ernie Jacobson moving to Hunslet and Herbert Ward rejoining Bradford FC.

A further issue was that the club was aggrieved at only having been granted one county trial match by the Yorkshire Union. The consensus within the committee had been ‘that to remain longer in the Rugby Union would be to court disaster.’ It was said that the players favoured the move and ‘a majority of the members of the club have for some time been hankering after a change.’

The Northern Union had an attraction for the rank and file players because it offered better fixtures and more local games. Not only did this promise higher gate revenues; a reduction in travelling also ensured lower costs and had benefit for the finances. Membership of the Northern Union was seen as an insurance policy to retain players but it also offered advantages for recruitment simply because the number playing the amateur game was diminishing.

Yet whilst these were considerations common to other clubs, there were also issues that were specific to Shipley FC in dictating the choice of the Northern Union. A defensive response to Windhill’s action was one such factor. Another was the impasse between factions of the Shipley membership to determine a viable future for the club and in the final event the old committee acted almost like receivers of the club. The lack of consensus among members threatened the club’s ability to deal with its increased indebtedness, a factor which had dissuaded people from getting involved with the management of its affairs. Accepting the status quo by default was therefore hardly an option and hence radical decision was considered necessary to reinvigorate Shipley FC.

Nevertheless, Shipley FC came close to be excluded from the Northern Union which would have been embarrassing having resigned from the Yorkshire Rugby Union. Club officials needed to lobby the Northern Union clubs both for late admission to the league and for fixtures to be arranged. Thankfully Antonio Fattorini of Manningham FC is known to have supported the application of Shipley in the face of opposition from others, including the members of Windhill. A suggestion that the club was in disarray is provided by the fact that Shipley’s opening game in the Northern Union was a crushing defeat at Dewsbury.

The end for Shipley FC

The move to the Northern Union was not popular with everyone. Shipley FC went from the top division of the Yorkshire Rugby Union to the second tier of the Northern Union in Yorkshire and this was the dilemma for Shipley FC, to be a big fish in a draining pond or to be a small fish in deeper waters. It also illustrated that defecting to the Northern Union was never going to be a magic solution to financial difficulties. And so it proved in 1899/00 when total income during the club’s first season in the Northern Union was only £112 – a reduction of £106, nearly half of that in the previous year – with a deficit of £23.

Shipley v Keighley, 25th December 1900

During the 1900/01 season the club made a determined effort to raise funds through various social events alive and the fund-raising efforts were nothing less than innovative. The Shipley Times of 8 September, 1900 announced that a grand bazaar was to be held at Christmas to remove the debt and on 29 December, 1900 it was reported that on Christmas Eve a ‘Corean Bazaar’ was held in the Shipley Central Infants’ School, opened by Percy Illingworth who declared ‘that a town so well organised and so well-contained as Shipley ought to have a football team worthy of the reputation of the place. He treated that all who appreciated football as an outdoor sport would endeavour to bring about that state of things, and would rally to the support of the committee in their effort to accomplish their laudable aims. He was an ardent supporter of all outdoor games and he did not think there was anything more suited to the temperament and genius of our people than Rugby football. It drew forth many qualities, among them courage, good temper, and endurance.’

Illingworth confessed that ‘he viewed with some feeling of apprehension the time of the split in Rugby football. He was one of those who thought that if a little more discretion had been shown on both sides they would still have been playing under the rule of the Rugby Union, a body which was now sadly in need of the help of its old Yorkshire supporters who were now under the Northern Union. He was not particularly fond of a crowd at football matches. He would prefer to see 10,000 playing than 30 playing and 10,000 watching; but he was afraid the club treasurers would not agree with him.’ His comments reveal that he was primarily concerned with the survival of Shipley FC as a local institution and that prejudices about the Northern Union were secondary to this. The support of chairman, William Denby – who was the owner of the dye works at Tong Park – similarly betrayed local patriotism. In acknowledging him, Illingworth said of Denby that ‘there was no good cause in Shipley which had not that gentleman on its side.’

Illingworth declared his hope that the bazaar would be a success to clear the club’s debt of £120 ‘a small one for a town like Shipley‘. The fund-raising efforts probably also encouraged support for the club through promotion of the holiday fixture with Keighley FC on Christmas Day, 1900 at the Ring Of Bells ground. It was reported in the Bradford Daily Telegraph that seven thousand people attended the game and in the absence of railway connections it was claimed that hundreds of people had resorted to walking down the Aire Valley en masse to Shipley.

It seems likely that the crowd for the derby game at Shipley constituted the record attendance at the ground which would have provided a considerable boost to the club’s finances. Whether the attendance was actually as high as seven thousand is questionable and whether the club was able to collect monies from all the spectators is another question entirely. For a start, the site of the ground was not extensive and the perimeter structures would have been rudimentary, possibly no more than tarpaulin covers with a couple of entrances at which gate money was collected.

From a financial perspective the 1900/01 season was something of a success for Shipley FC. It was subsequently reported in April, 1901 that the club had ended the campaign ‘£50 better off than at the commencement of the season’ which probably encouraged a sense of optimism among Shipley supporters that the club could stabilise its affairs and enjoy a revival.

There were no further attempts at merger with either Saltaire or Windhill but it is doubtful whether this could have transformed the prospects of Shipley FC. The experience of football in the Spen Valley had demonstrated that amalgamation was easier said than done. For example in 1899 the officials of the Liversedge and Heckmondwike clubs had resisted coming together despite their financial difficulties and the fact that the Spen Valley – like the Shipley district – could not support two professional sides. The case for merger of those clubs was strong and the Bradford Daily Telegraph of 8 April, 1899 ascribed the reason why it didn’t happen to the self-interest of the individuals concerned. The following year Liversedge combined with Cleckheaton FC following the latter’s secession to the Northern Union. However, this arrangement was generally accepted to have been a failure in terms of both financial outcomes and playing performances. The experience of Liversedge / Cleckheaton may have reinforced attitudes that fusions were not the best way to ensure survival.

Indeed, it is telling that apart from Liversedge / Cleckheaton no other amalgamations occurred among junior rugby clubs in West Yorkshire and besides. Such was the independent-mindedness and competitiveness between rivals that the emotional baggage of any merger was always going to be a major obstacle. With the Saltaire club having wound-up in 1898, the Shipley committee must have concluded that if Windhill FC was left to collapse under its debts then this would be a preferential outcome.

The record of Shipley FC in the Northern Union was modest. Denied a place in the Northern Union Challenge Cup competition of 1899/00 (presumably on account of late registration), in 1900/01 it suffered a first round defeat at Stockport.

Shipley was one of the stronger sides in the Yorkshire Second Competition Western Division and in 1900/01 there had been a close race between Heckmondwike, Shipley, Sowerby Bridge and Keighley for the championship. However, it was Heckmondwike who were champions of the division during the two seasons of Shipley’s membership.

Yorkshire Sports cartoon, February 1901

In April, 1901 the Shipley members were informed that the Earl of Rosse had recently sold the club’s ground opposite its headquarters at the Ring Of Bells for residential development and that the club had been given notice to vacate by the end of the month. The short notice period is worthy of mention as it hardly provided security of tenure for the club, another factor conspiring against robust finances or more extensive development of facilities.

Having investigated the possibility of a new ground the leadership decided that it could not afford the cost of levelling the land and building a retaining wall. (The site of the ground is reported as having been ‘between the railway and the canal with its entrance in Ashley Lane’ but there is also reference to a field at Jane Hills.) In July, 1901 it was decided to disband Shipley FC but at least the club avoided the indignity of Bingley FC the previous December, whose landlord distrained for non-payment of rent and removed the goal posts at its ground.

Nevertheless, Shipley FC had outstanding debts of £83 and its members were liable for this. In October, 1901 the auction of the remnants of the club’s two wooden stands realised only £7 and additional fund-raising activity had to continue until the end of the year.

Within ten years of the rugby split that had occurred in 1895, the Bradford district had become a soccer stronghold. The city boasted the first Football League club in West Yorkshire and the Bradford & District Football League comprised local sides from every suburb and village. Rugby was played in only a handful of schools and most striking of all, the junior rugby clubs of what is now the Bradford Metropolitan District were virtually extinct – the most notable exception being Keighley FC who by this stage was one of the leading Northern Union sides in the county. (The only other survivor was Wyke FC, again a member of the Northern Union.)

The emergence of Shipley Victoria FC after the winding-up of Shipley FC may have been an attempt by former Shipley members and enthusiasts to continue playing Northern Union rugby. However Shipley Victoria existed at a very junior level as members of the second division of the Bradford & District Rugby Union and had a fleeting existence. The team ground shared with Windhill Rangers at Cowling Road, Windhill.

The end of Windhill FC

No further attempt was made by Windhill FC to assume the ‘Shipley’ identity and in July, 1901 the Shipley members rejected a proposal for a committee to investigate the possibility of merger with Windhill FC. (Irrespective it is unlikely that Windhill members would have had any enthusiasm to combine and take responsibility for the Shipley debts).

Windhill FC eventually disbanded at the end of the 1902/03 season, succumbing to its financial difficulties which were compounded by poor accounting and weak controls. In March, 1903 there was embarrassment at the fact that the club had been unable to fulfil a fixture at Sowerby Bridge on account of not having sufficient funds to pay the rail fare. During the course of inquiry it emerged that a cheque payment from a benefactor had been ‘lost’, a not dissimilar situation to that in 1888 when the financial records had gone missing. The donation had been made by Sir Fortescue Flannery, by this time the Shipley MP (1895-1906) and his support for Windhill FC is another example of the far-reaching links between Conservative politicians and football clubs in the Bradford district and surrounding areas. The Shipley Times of 6 March 1903 disclosed the internal investigations within the club and recriminations: ‘In the course of a heated discussion it appeared that the financial difficulties of the club were due to a great measure to the way in which the books of the club had been kept… and that the present officials thought that the interests of the club would be best served by ‘hushing’ the matter up.‘

Whether Windhill FC enjoyed favourable political patronage is a matter of speculation but it is notable that alone of other junior rugby clubs in the Bradford district and vicinity, its ground at Crag End was safeguarded thanks to civic intervention. In January, 1901 Shipley District Council agreed to the purchase and ‘laying out’ of the Windhill Cricket & Football Field as a public recreation ground at a cost of £3,000. The Shipley Times of 2 February reported that ‘the proposed recreation ground at Windhill was in a densely populated district, and it was thought that it would very unadvisable to let it be disposed of for building purposes.’ It is unclear if the Windhill club enjoyed beneficial lease arrangements from the new ownership but the decision is notable, representing as it did a fairly enlightened policy. (Arguably the proximity of alternative recreational facilities at Red Beck Fields dissuaded Shipley Council from seeking to protect the home of Shipley FC at the Ring of Bells ground from property development. However, being situated in a relatively affluent area, the case for intervention would have been much weaker.)

At the end of June, 1904 nearby Idle FC was wound up. Bumper receipts from its cup tie reply with Manningham FC the previous February had provided temporary respite but the club was not viable and its members recognised the futility of continuing. Blame for the club’s demise was attributed to the Northern Union. Such sentiments were consistent with those of many other rugby followers in Bradford and reflected growing disenchantment with the code around that time.

The fate of Keighley FC

Keighley FC had similar pretensions to those of Shipley and had finished as runners-up in the top tier of the Yorkshire Rugby Union in 1897/98 and then 1898/99. It had previously been champions of the YSC second division in 1896/97 (twelve months after Shipley FC won the same title). Shipley’s defection to the Northern Union in 1899 removed a key competitor and in 1899/00 Keighley secured the YSC first division championship (again, emulating Shipley’s achievement the previous year). Nevertheless, rumours in the Bradford Daily Telegraph in January, 1900 of Keighley following Shipley into the Northern Union proved accurate and at the end of the season Keighley seceded alongside the Bingley, Cleckheaton, Otley and Wyke clubs.

In 1900/01, league rivalry between Keighley and Shipley was renewed as fellow members of the Northern Union’s Yorkshire Second Competition Western Division. The motives of Keighley FC had been entirely financial, specifically to benefit from better crowds and to reduce travelling costs. In terms of fostering local interest, membership of the league was seemingly ideal with a total of fifteen other clubs in the division and no more than twenty miles between them. Five of those were based in Calderdale and five were from Airedale – Bingley, Idle and Windhill in addition to Keighley and Shipley. (The remaining clubs were Dewsbury, Heckmondwike, Kirkstall, Birstall and Otley.)

In 1901/02, with the disbanding of Shipley FC, it was Manningham FC who became local rivals for Keighley FC. The following season Keighley finished above Manningham to secure promotion to the top tier of the Northern Union as champions of the newly formed second division (that embraced Lancashire and Yorkshire clubs).

Although Keighley FC was relegated at the end of 1903/04, in 1905/06 it was ranked fifth highest in the north and in 1906/07 it was fourth (pictured below), finishing above Bradford FC. Prior to the outcome of World War One it was the strongest club in what is now the Bradford Metropolitan District. It was a remarkable ascendancy, an achievement that defied Shipley FC. Arguably Keighley benefited from the demise of Shipley in 1901 and the conversion of Manningham FC to soccer in 1903 – as Bradford City AFC – because it was able to attract rugby enthusiasts along the Midland Railway / Aire valley corridor. Similarly in 1901 and 1903 it was able to recruit former Shipley and Manningham players.

In November, 1907 when the new Bradford Northern club played Keighley at Greenfield it was remarked that there were as many Bradford district players in the Lawkholme Lane side as the home team and that the fixture could hence be classed as a local ‘derby’.

Had Shipley FC not faced eviction in 1901 and the expense of relocation, quite possibly its members would have prolonged the struggle and it might have been Shipley and not Keighley – now known as Keighley Cougars in the Rugby League – who survived.

A new Shipley club

The Shipley identity was revived in September, 1908 by members of the Bradford Wanderers rugby union club who opted to rename their organisation. The Wanderers played in Shipley and the club’s decision was intended to encourage local interest – prompted perhaps by the revival of Otley RFC the previous year. It revealed a distinct identity and sense of local autonomy that is not so quaint as might be presupposed.

The extent to which Shipley people were independent-minded in relation to Bradford is notable and provides historic context to recent suggestions about Shipley seceding from the jurisdiction of the wider Bradford Metropolitan District. In 1938 for example, the Shipley Times & Express reported celebrations in the town when the compulsory incorporation of Shipley into the Bradford district was rejected in Parliament. It echoed similar sentiments in 1901 when Baildon residents had lobbied to remain within the Shipley district rather than be absorbed into Bradford. The resistance was as much driven by economic reasoning as sentimentality and ever since the 1880s there had been sensitivity in Shipley about the cost of water supplies from Bradford Corporation. Shipley people were also mindful about higher property rate levies in Bradford.

The Bradford Wanderers club had been formed in 1899 and originally played its games at Birch Lane which had been vacated as a result of the Bowling Old Lane rugby section disbanding in 1897. In 1903 the club had relocated to Red Beck Fields off Otley Road and used the nearby Branch Hotel as its headquarters. (This was the same ground that had been used by Manningham Albion – a predecessor of Manningham FC – in 1879/80 and until 1883, by the original Shipley FC. Sadly the Branch Hotel is no more to be seen having been demolished in August, 2018.) Bradford Wanderers became known as the ‘Red Beck Amateurs’. However, in 1906 when the club merged with Bradford Rangers it became known as plain ‘Bradford’, thereby implying the inheritance of the town club’s rugby union heritage.

The reason for the merger was to remove competition between Rangers and Wanderers for new recruits. By combining it was felt that standards could be improved and the future of rugby union in the area safeguarded. Nevertheless, the move was not welcomed by all and a new club, Horton RUFC was formed. A crucial point of difference was that the Horton club was based in Bradford and more convenient to those living in the south of the city – much the same factor that had driven the way in which rugby had originally evolved in the district during the three preceding decades. (At the time of the merger it was reported that the combined club had hoped to play at the former Lidget Green ground of Bradford Rangers. However it is unclear why this did not happen and how it was that the Horton club adopted the ground.)

The emergence of Horton undermined the initiative at Shipley and hence within two years came the seemingly radical measure of changing the latter club’s name. The decision to forsake the Bradford identity for that of Shipley needs to be seen in the context of the ‘Great Betrayal’ in 1907 when rugby had been abandoned at Park Avenue. This had led to the emergence of two new sporting identities – Bradford Park Avenue and Bradford Northern – and the disappearance of the ‘Bradford’ rugby club. Mindful of possible confusion, the renaming of Bradford Wanderers to ‘Shipley’ can be interpreted as signifying a fresh start for rugby in the area and the adoption of a distinct identity. Furthermore the club did not have its base within the Bradford boundaries and it could appeal to those who had followed the original Shipley FC. Undoubtedly there would have been a sentiment among local rugby followers of unfinished business from the previous decade as well as an eye to what Keighley FC had achieved.

The appeal to ‘local patriotism’ in Shipley may also have been encouraged by long time benefactor and patron Percy Illingworth who was president of Bradford Wanderers and by this time also the MP for Shipley (a Liberal, elected 1906 and serving MP until his death in 1915). The underlying motive for a relaunch however was to attract new recruits to the club to safeguard its survival and give vibrancy. The fact that the club had found itself struggling to compete with Horton RUFC – by this time established as the leading rugby union side in the Bradford district – was the fundamental issue.

The challenge for the club was not so much one of finance; it was the struggle to recruit new players. By this stage there were few who played rugby union and before long came the realisation that Shipley RFC was disadvantaged by being based at the Red Beck Fields which it shared with the town’s soccer side that played in the Bradford & District League. In December, 1909 a home fixture was arranged with Skipton at the Stanacre ground of Victoria Rangers (who had disbanded the previous summer and converted from Northern Union to soccer). The Leeds Mercury of 1 January, 1910 reported the experiment and said that the club was even considering a revival of its earlier ‘Bradford Wanderers’ identity, a decision that was clearly driven by recruitment needs. Ultimately the Shipley identity was sacrificed and the club – renamed as Bradford Wanderers – later everted to the tradition home of Bradford rugby at Apperley Bridge.

Bradford Wanderers briefly disbanded in 1912 before reforming once more. The club’s somewhat transient existence came down to the difficulty of recruiting new members, a malaise that continued to affect rugby union in Bradford with reliance upon former Bradford Grammar School (and to a lesser extent Woodhouse Grove School) boys to fill the ranks. Immediately after World War One the remaining members of Bradford Wanderers joined those of Horton to form Bradford RFC at Lidget Green. [Refer here about the revival of Bradford rugby union in 1919]

Shipley FC remembered

Virtually nothing remains other than Baines trade cards as a reminder that Shipley had its own rugby club. Yet whilst the history of the Rugby League has tended to focus on the big names, the fate of junior sides such as Shipley FC was equally significant. The story of Shipley is part of the narrative of how rugby became commercialised as an entertainment industry and of how this impacted on the fate of smaller clubs. The case of Shipley FC also contradicts the prevailing version of the 1895 split in English rugby that junior sides in Yorkshire were enthusiastic about seceding from the Rugby Union and that class identity was a driver of this.

Although its playing colours of black, scarlet and blue were more distinctive than its playing record, Shipley FC should be remembered as one of those bread and butter clubs who were part of the sporting revolution that took place in the last quarter of the nineteenth century in the Bradford area. The story of Shipley FC is also a reminder that no meaningful history of rugby at a national level can be written without considering the fate of unglamorous and long forgotten local sides.

By John Dewhirst [ @jpdewhirst ]

**My thanks to Stuart Quinn for allowing me to feature two of his Shipley cards (pub Baines of Bradford) in this feature.

Links to other online features:

More on the history of Bradford rugby on VINCIT

How the Bradford case study contradicts the orthodox view re 1895

The revival of Rugby Union in Bradford in 1919

The author has written widely about the history of Bradford City AFC. His books, ROOM AT THE TOP and LIFE AT THE TOP (pub bantamspast, 2016) explain the origins of sport in Bradford, the development of sporting culture in the town in the nineteenth century and of how sport came to be commercialised. He provides the background to how Manningham FC and Bradford FC became established and of how they converted to professional soccer in the twentieth century as Bradford City and Bradford Park Avenue. John is currently working on a new history of the rivalry of the two sides as members of the Football League in WOOL CITY RIVALS (FALL FROM THE TOP).