Valley Parade has hosted football and rugby but it tends to be overlooked that it was originally also known as an athletics venue, hosting annual athletic festivals between 1887-96.

Athletic festivals became established as a popular phenomenon in the Bradford district from the staging of the first by Bradford Cricket Club, 150 years ago in July, 1869. It was an era when people were actively seeking new forms of leisure and earlier features on VINCIT record the origins of cycling in Bradford the same year and the formation of Bradford Amateur Rowing Club in 1867. Similarly Bradford FC had played its first competitive game in February, 1867. This feature examines the origins of athletic festivals in Bradford including those held at Valley Parade.

The love of deep pockets in Bradford

In April, 1868 a correspondent (‘HW’) wrote to the Bradford Observer: ‘I have often wondered how it is that in a town like Bradford, noted for its love of outdoor sports, no movement has ever been made to establish an amateur athletic yearly meeting for running, jumping etc.’ The letter called upon local cricket clubs to organise such an event, possibly at the ‘Old Cricket Ground, Horton Lane.’

A week later, on 30 April, 1868 the correspondent, ‘Gymnast’ who had previously encouraged the formation of a rowing club provided his explanation: ‘No matter how much the people of Bradford love out-door sports, they love their pockets much better, and have a great objection to disburse their contents in support of that which does not repay them with interest.’

‘Gymnast’ mentioned that consideration had already been given to organising a festival but it had not been progressed, possibly on account of the fact that events in Huddersfield and Manchester had been loss-making. ‘Gymnast’ argued for the need for broad support to make a venture successful and he called upon the officers of the rifle corps and artillery corps, the committee of the Bradford Old Cricket Club and the Gymnastic Club (on Salem Street) to establish an Amateur Athletic Yearly Meeting.

It is interesting that there was no reference at this time to Bradford FC which was obviously considered peripheral. Instead the letter demonstrates the extent to which the Bradford (Rifle and Artillery) Volunteers were influential with regards to physical activity, a reminder of the fact that sport in Bradford has a strong military heritage.

The identity of ‘Gymnast’ was not revealed, but in a subsequent letter on 7 May, 1868 ‘HW’ presumed him to be a member of the Bradford Gymnasium and my belief is that it was B. Wright who was secretary of the Bradford Gymnastic Club and a founder member of the Bradford Rowing Club the previous year. Towards the end of 1868 came an exchange of correspondence in the Bradford Observer calling for a public gymnasium to be established which referred to the fact that ‘the private one now in existence is not at all well supported.’

What can be inferred from the letter written by ‘Physique’ dated 9 November is that people could not justify subscriptions for a private gym which says a lot about the viability of commercial leisure provision at this time, not to mention the attraction of joining the Volunteers to get free access. If indeed ‘Gymnast’ was involved with Bradford Gymnasium Club his motive in encouraging a Bradford rowing club or a Bradford athletics festival may have been to drive membership of his gym as a means of training.

On 17 December, 1868 ‘Physique’ again wrote to the Bradford Observer calling for a public gymnasium to be opened in the town. He suggested that during the day it could be used for ladies’ classes and mentioned the Liverpool gymnasium where ‘certain days are devoted to the ladies, they having a costume properly adapted for the exercise.’

A later editorial in the Bradford Observer of 2 January, 1869 stated that the writer’s ‘predilections are on the side of open-air pursuits rather than on that of the indoor turning of cranks, or climbing of poles, or twisting around bars…in awful contortions.’ I suspect that this was a view shared by many and the subsequent popularity of athletic festivals and football matches provided the fresh air and a new form of exhibitionism. Notwithstanding, gymnastics remained popular in Bradford and was later encouraged as a form of Muscular Christianity in the 1870s with a gymnasium operated by the Bradford Church Institute.

The Bradford All Saints Gymnastics Club gained a reputation as one of the foremost clubs in Yorkshire in the first decade of the twentieth century. The club claimed its origins to have been in the 1860s, quite possibly from the original gym on Salem Street. Gymnastic displays by the Bradford All Saints Gymnastics Club were regular events at both Park Avenue and Valley Parade either side of World War One, an historic reminder of how athleticism and football later evolved from gymnastic activity.

The first athletic festival in Bradford

Possibly in response to the correspondence the previous year, an inaugural athletics was staged on 24 July, 1869 at the Bradford Cricket Club ground on Great Horton Road which served as the de facto leisure centre of the town. The event was supported by the Rifle Volunteers with Lieutenant-Colonel Hirst of the 3rd Yorkshire (West Riding) Rifle Volunteer Corps acting as president and the band of the corps being present. It proved to be a success, attracting between three to four thousand spectators including ‘many of the elite of Bradford.’

Following the lead of Bradford CC in July, 1869, athletic festivals became commonplace in the following decade and were staged by other local cricket clubs including Shipley, Bradford Moor (later staged at Thornbury United CC following loss of the Bradford Moor ground), Bradford Albion, Eccleshill and Undercliffe. Festivals on the Ilkley racecourse were similarly inaugurated in 1873. One of the pre-eminent organisers of events at Eccleshill and Undercliffe was John Nunn who was at the forefront of promoting athleticism in Bradford. Events were staged in neighbouring towns and villages which attracted Bradford contestants, examples of which in 1869 at Huddersfield, Guiseley and Burley.

The final athletic festival to be staged at the Bradford CC Great Horton Road ground was in 1874. Shortly after the club disbanded following the sale of the ground for residential development and in 1879 the call to develop Park Avenue as a dedicated sports enclosure was driven in good measure by an urge to revive the annual athletic festivals in the town. It was no accident that the name of the newly formed club which occupied the ground was the Bradford Cricket, Athletic & Football Club. (The first festival at the new Park Avenue enclosure took place in July, 1881.)

The cult of athleticism

Reporting on the Leeds athletic festival, the Bradford Observer of 13 September, 1869 commented that ‘open air festivals, embracing a programme of running, walking, ‘putting the stone’ and throwing the hammer are now becoming popular’ and referred to events at Mirfield, Guiseley and Buttershaw since the festival at Bradford Cricket Club two months previously. The attendance at Leeds however was less than that at Bradford on account of the weather. Festivals became seen as a way of attracting crowds to the extent that even the Bradford Floral & Horticultural Society resorted to organising such an event at its Peel Park show in July, 1870. In 1873 Bradford CC later relied upon its athletic festival to offset losses from staging cricket.

However as if to anticipate the charge that athletic festivals were commercial ventures with the intent of personal reward, it was stressed that they were organised to raise funds for charity. This endowed further respectability and further distinguished them from the sort of events staged at Quarry Gap. It meant that athletics was firmly associated with a more noble cause or ideal and avoided any embarrassment about making a profit. In Bradford, the principle of raising money for the town’s charities became a central tenet when staging sport. In this way the practice of athleticism was portrayed as a force for good and this had a major influence on Bradford’s sporting culture.

Events at these festivals were what we might expect at a church garden fete rather than being recognisable as modern athletic contests. Those at the inaugural festival at Bradford CC in 1869 were typical: ‘Walking over two miles; throwing the hammer; putting a shot; flat race over 100 yards / 220 yards / a quarter of a mile / one mile; running high jump; standing wide jump; one mile bicycle race; 100 yard hurdle race over eight flights; quarter hurdle race over twelve flights; and throwing the cricket ball.’

They could be characterised as short duration, intensive affairs sufficient to command spectator appeal. They could equally be described as curio events. None of them constituted tests of endurance but I suspect that they were matched to the fitness of contestants. Neither did the selected events demand an onerous training regime. As a measure of performance, in 1869 the 100 yard flat race was won in just over ten seconds.

The suggestion in the Leeds Times on 13 March, 1875 that ‘the annual athletic sports, where the ‘youth and beauty’ of the district assemble to witness the manly efforts of their male friends in games which rival the Olympic sports of old’ seems a bit wide of the mark in terms of describing the events. However, a consistent theme in newspapers is that the festivals attracted a good proportion of female spectators.

Despite the standard the contests were taken seriously and the Bradford festivals consistently attracted contestants from across the country with 206 entrants in 1869. At first, medals and cups were awarded to the first three finishers but within ten years, bigger prizes were at stake and by the end of the 1870s local festivals were attracting large crowds. In July, 1879 as many as ten thousand people attended the Bingley Athletics Festival.

The different festivals vied to attract contestants through the range of prizes that were offered and by introducing new contests, such as ‘Cumberland and Westmoreland’ wrestling at Bradford Albion’s festival on Horton Green in July, 1875.

The respectability of these athletics festivals contrasts to that of the touring ‘English Champions’ show which visited the City Sporting Grounds, Quarry Gap at Laisterdyke in August, 1862. On that occasion the star billing had been an American Seneca Indian, ‘Deerfoot’ who contested a four mile race, winning in just over twenty minutes. The show attracted fifteen hundred spectators with other events such as sack racing, ball gathering, ‘pole-leaping’, a 220 yard race and a one mile race in which local people were invited to participate. The show was part of a tour of the British Isles (which had visited variously Cork, Edinburgh, Dundee, Glasgow, Newcastle, Carlisle, Kendal, Lancaster, York, Malton and Scarborough before reaching Bradford) and would better be described as a travelling athletics circus. Contestants to the four mile race were instructed to wear proper costume – long drawers, guernseys and short-coloured over-drawers whilst Deerfoot wore his Indian costume.

Another example of an event at Quarry Gap that combined athletic accomplishment with showmanship was that in September, 1864, namely the attempt of a 36 year old local lady by the name of Emma Sharp (the wife of a mechanic from Bowling) to walk 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours. The feat attracted much interest and it was reported that on one occasion ‘5,000 females were in attendance.’ The Bradford Observer of 3 November, 1864 reported on the success of her endeavour which had taken place during the preceding six weeks ‘exciting great interest among the sporting and betting fraternity, of whom there have always been some present both night and day.’ It added that ‘Mrs Sharp had gained weight… and grew weary of her task during the latter days, declaring she would never repeat it.’ Admission was charged to the event and it was claimed that Mrs Sharp’s portion of the receipts was at least £500.

Although the athletic festivals remained oriented towards spectator spectacle, the degree of showmanship was replaced by more earnest endeavour involving a broader base of local participants and a number of visiting contestants. The affairs were considered to be far more serious and they also had the endorsement of local dignatories. Thus whereas the Quarry Gap entertainments were typically regarded as a means to generate the sale of alcohol and encourage gambling (the case of a £50 foot race in May, 1863 and an arrow throwing context in March, 1868 being such examples), the festivals were linked with raising monies for local charity and interest was encouraged by the honest competition and rivalry of local men. The venues – typically cricket grounds – were also significant in that the festivals derived respectability from being staged at other than Quarry Gap which was associated as a show ground and between 1855 and 1868 was better known for staging horse racing.

In 1883 The Yorkshireman later made disparaging remarks about the presentation of prizes at the Bradford Sports festival that confirms the snobbery about Quarry Gap… ‘It lowers the standard of our manly English sports, and reduces such a ground as Park Avenue to the level of Quarry Gap and similar places.’

A comment in the Bradford Observer of 1 June, 1865 that ‘gambling produces a mania for all that is sportive and sensational’ summed up the prejudice felt by many towards sports events and the sort of showmanship at Quarry Gap. The link with gambling was thus the biggest obstacle to acceptance of sport. Indeed, what is significant is the extent to which gambling and alcohol dominated popular entertainment in the nineteenth century and there are many examples of contests being staged for ad hoc wagers in front of crowds. (One such was reported in the Leeds Times of 13 September, 1879 concerning a race on what is now the traffic congested A650: ‘A two miles trotting match for £50 took place on the Bradford and Keighley road, the starting point being the milepost opposite the old Sorters’ Gardens and the finishing point being Nab Wood. There were about 2,000 persons on the highway to witness the race, a large number coming from distant places in vehicles.’)

The Huddersfield festival was considered one of the bigger profile events in West Yorkshire and also one of the longest established (first staged in 1865 – in fact, it is likely to have been one of the first in the county).

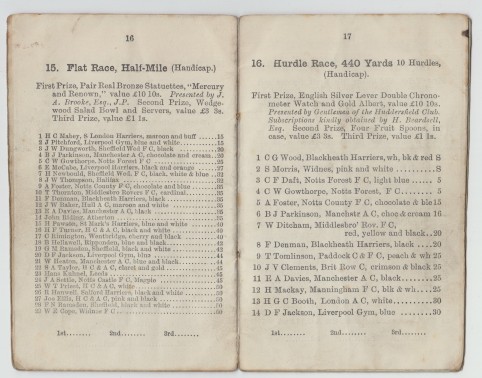

The prestige of the competition and the value of prizes helped attract contestants from afar as the pages below attest. The colours of the runners were not those of individual clubs, rather of the individuals themselves (like those of jockeys) and the variety of combinations would have created a colourful display. In practice the colours were most likely to have been displayed with sashes or belts rather than jerseys.

The other observation is that whilst each runner was affiliated to a sports club, the names of the organisations reveal that they were not limited to athletic clubs but were members of running clubs (ie South London Harriers), gymnasia (ie Liverpool – presumably the same establishment as that which existed twenty years before as referred to above) as well as football clubs – the latter comprising both rugby and association football. Accordingly the races would have pitched competitors from a variety of sporting backgrounds but as far as the Victorians were concerned, they were all athletes who happened to participate in different forms of athleticism. The basis of a successful event was therefore a good field of events tempted by the prizes on offer but it also required the chance benefit of good weather. .

A central feature of the athletic contests was the silverware awarded to the winners. The Bradford firm of Fattorini & Sons derived considerable benefit as the foremost local supplier of trophies and medals which were invariably displayed in the windows of its shops on Kirkgate and Westgate in Bradford. This undoubtedly added to the excitement and anticipation ahead of festivals, providing a degree of glamour to the occasion. Tony Fattorini’s enthusiasm for athleticism allowed seemless networking opportunities and helped his firm establish its reputation as the leading designer of sports trophies in England, culminating in the design of the new FA Cup in 1910 of which Bradford City AFC was the inaugural winner in 1911.

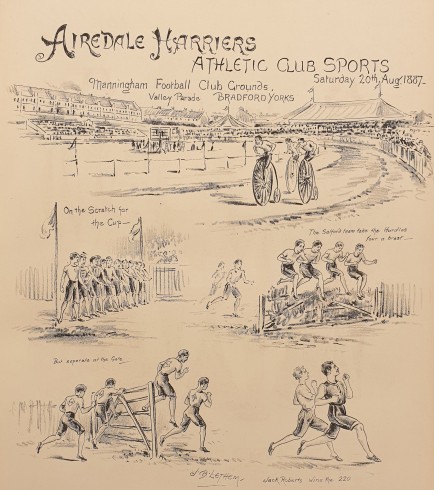

Valley Parade’s first athletic festival: 20th August, 1887

When the Manningham FC management committee looked for a new ground in 1886, the original intent was that it would stage other activities such as cycling and athletics alongside rugby football. Although it was recognised that this could have financial benefit, it was also regarded as a means by which the ground would establish for itself a higher profile as more than just a football enclosure. Amon the Manningham FC membership there was also enthusiasm for athletics and John Nunn, by this time a member of the club, could be relied upon to help organise and promote athletic events.

Manningham FC had in fact staged its first athletic festival in conjunction with Airedale Harriers at its Carlisle Road ground in September, 1885 and this was considered a mark of the growing respectability of the club. The staging of athletic festivals was thus seen as a way in which Valley Parade might establish its status as a leading sports ground with reflected glory accruing to Manningham FC.

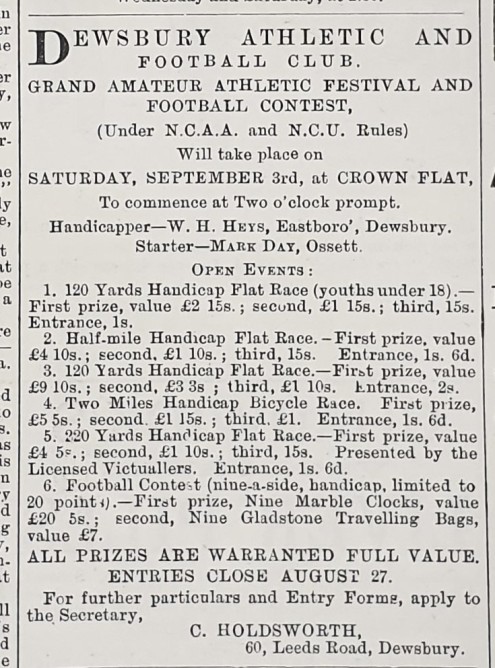

At the time, the leading athletics club in the district was Airedale Harriers, of which coincidentally Tony Fattorini was a member. It had been hoped that the club could stage an athletic festival at Valley Parade in the summer of 1886 but the ground was not ready and so the event was staged at Lady Royd Cricket Club, Allerton which attracted a crowd of four thousand. The adequacy of the Lady Royd venue had been criticised – it was said that ‘the provision for keeping spectators in check proved inadequate and… people hampered the runners’ – which raised expectations about Valley Parade that staged its first festival the following year. The advert below appeared in The Yorkshireman.

The following graphic was published in the Manchester publication, Black & White and to my knowledge is the oldest surviving depiction of Valley Parade. It will be noted that a marquee was erected on what is now the site of the Kop. The ground had a running track around its perimeter that could also be used for cycle races.

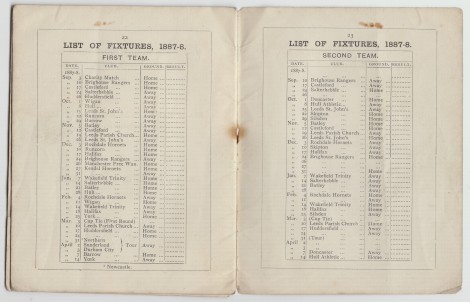

The Manningham FC programme for the event provided a race card of the various contests as well as fixtures for the forthcoming season, 1887/88. The presentation of prizes by Sir Henry Mitchell affirmed the respectability of the event. (Images courtesy of Jon Longman.)

The inaugural Valley Parade event attracted contestants from across the north and at stake was an impressive array of prizes, the most prestigious of which was an attractive trophy for the winners of the three mile inter-club steeplechase. Manufactured by Fattorini’s, this had a reported value of £40 which was in excess of the average annual wage for a workman. There were three teams of four runners apiece competing for the prize which was won by Salford Harriers. It was said that they had ‘a ridiculously easy journey’ finishing two laps ahead of the fastest runner from the Bradford Trinity club whilst none of the Airedale team finished. The achievement of Salford Harriers was celebrated in the Manchester publication Black & White (pictured).

Unfortunately the attendance at the Airedale Harrier’s Festival was considered disappointing and it was acknowledged in the press that a profusion of other athletics events in West Yorkshire had saturated public interest. For instance the Bradford Athletic Club festival had taken place at Park Avenue the fortnight before the one at Valley Parade and was generally regarded to be far more prestigious. The Bradford Daily Telegraph reported on 23 January, 1888 that it generated receipts of £464 and a profit of £379. Inevitably there were unfavourable comparisons drawn in relation to that in Manningham.

The following listing of festivals in August and September, 1887 attests to the prevalence of events in the north of England and the week after the one at Valley Parade, Bowling FC staged its own athletics festival at Usher Street. It was a mark of status that a club had the wherewithal to stage such an event yet few could match the profitability of the Park Avenue event.

Proxy competition

Local (rugby) football clubs effectively became involved in a proxy competition to stage athletic festivals, with the offer of ever more generous prizes. Undoubtedly this mirrored the intensification of football rivalries during the 1880s as Yorkshire rugby became increasingly commercialised.

During the 1880s the programme of events became progressively more codified for example with standardised running events that would have further attracted betting interest. From 1885 there were more bicycle and tricycle competitions which would have reflected the fashion of the time and also provided more of a spectacle around the perimeter of the cricket ground. However even in 1896 (the final year that the festival was staged) the events continued to include the more sublime such as the 200 yard association football dribbling race but the festival of that year remained popular with 7,000 spectators, 300 entrants and prizes worth £200.

The value of prizes on offer at the athletic festival at Park Avenue in July, 1893 was high in the context of average weekly wages which were in the region of 30 shillings (£1.50) for skilled men. Whilst participants competed as amateurs, the rewards of success were not insignificant and footballers were at a distinct advantage in these events given that the general level of fitness and participation in sport by most people was low. Organisers of athletic contests would have also welcomed the entry of footballers to attract spectators. One such player, Fred Cooper (who joined Bradford FC the following October) was particularly successful in short distance sprints and during the summer months attended various festivals in England as well in South Wales where he had been brought up. (On the same weekend of the Park Avenue festival he had been a prize winner at the Cardiff athletics festival.) Other prominent sprinters who played for Bradford FC included Tommy Dobson and Frank Ritchie.

After 1986 annual sports festivals continued to be staged at Park Avenue but on a far more low key basis with a headline objective of charity fund raising. These continued into the twentieth century, latterly in the guise of the Bradford Police Sports until the 1960s. The golden era of athletic festivals in Bradford however remained the 1880s.

by John Dewhirst Tweets: @jpdewhirst

From his book ROOM AT THE TOP. Other content written by the author about the history of football in Bradford is published on his blog, WOOL CITY RIVALS where you can access his features published in the Bradford City AFC matchday programme as well as book reviews and archive images.

==================================

VINCIT provides an accessible go-to reference about all aspects of Bradford sport history and is neither code nor club specific. We encourage you to explore the site through the menu above.

Future articles are scheduled to feature the military heritage of sport in Bradford, the forgotten sports grounds in the Bradford district, the politics of Bradford sport and its sports grounds, the financial failure of football clubs in Bradford and the history of Bradford sports journalists.

Contributions and feedback are welcome.

==================================