By Dave Welbourne

The front page of the Telegraph and Argus on March 20th., 1950 announced that Bradford City and Bradford Park Avenue were in “the doldrums”. (1) The crisis continued throughout the 1950s, and led some to claim it was “a decade to forget”. Why had Bradford football descended into this?

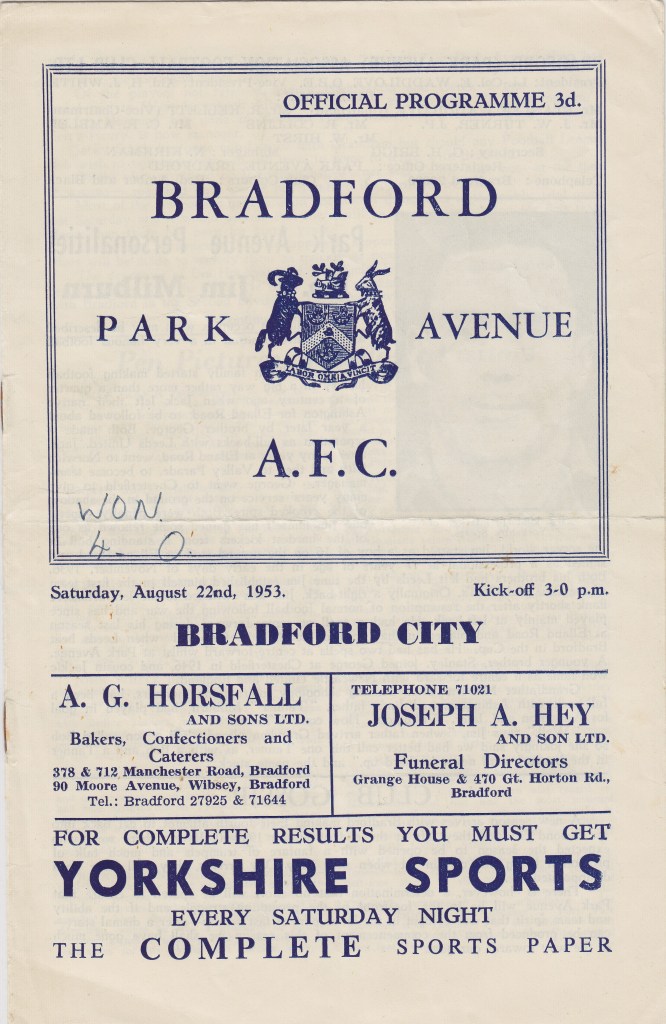

In the early fifties I was a Bradford Park Avenue supporter watching the likes of Downie, Horsman, Suddards, Deplidge, Crosbie and Haines. By the end of the decade I had been converted to Bradford City. Players from that era still run off my tongue: Smith, Flocket, Mulholland, Lawlor, Robb, Stokes, Reid, the Jackson twins, McCole, Webb, etc. It was a period of contrasts and transitions as the country underwent post-war reconstruction. Professional football too was to undergo significant change, but the two Bradford clubs were to have rock bottom experiences.

For me, it all began when my dad took me to watch Bradford Park Avenue, captained by his friend, Les Horsman , who was from Burley where we lived. We caught the bus to Bradford’s Chester St. bus station, then joined the crowds walking up to Great Horton on what seemed like an endless trek. It was strange how people seemed to accelerate the nearer they got to the ‘Doll’s House’ style Archibald Leitch stand which was similar to Fulham’s Craven Cottage. Supporters came by train, tram, car and foot. Opposite the ground was Horton Park Station, but this closed down in 1952, though it was used later for big events.

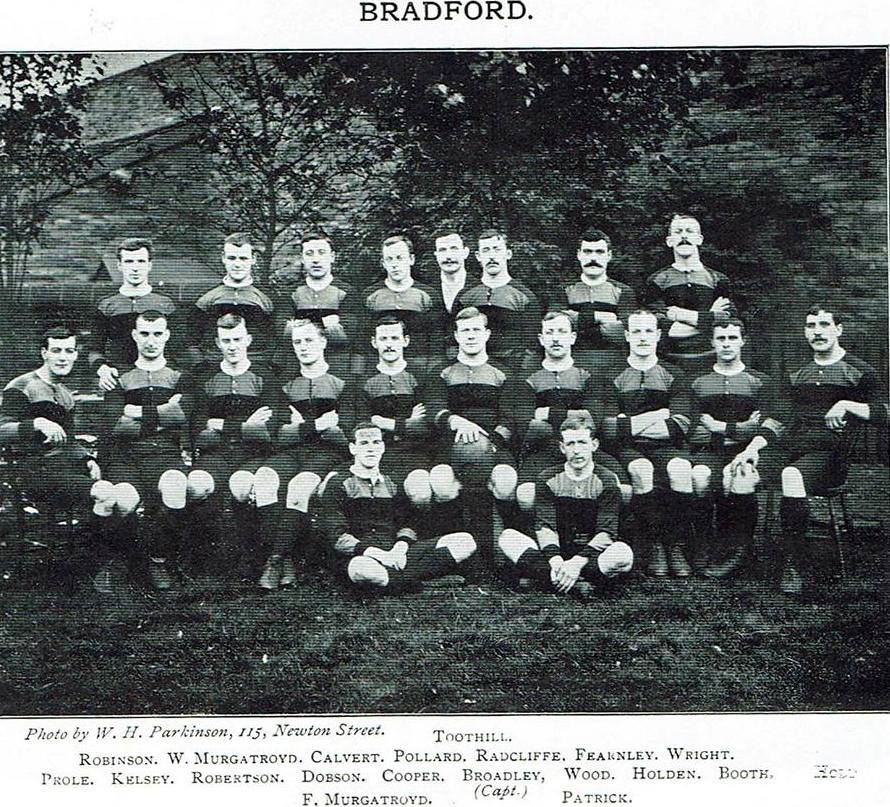

The Bradford familiar to football supporters retained many of its Victorian features. In the nineteenth century the area around what became the Park Avenue ground was green fields, and Little Horton had an abundance of large Victorian houses. For the middle classes it had a prestigious image. In contrast, as the century progressed, Bowling, Great Horton, and Manchester Road were lined with rows of back to back textile workers houses, mills, factories, warehouses and tall chimneys. (2) To escape these crowded, polluted urban areas, the middle classes had generally moved out.

Immigrants then spilled into these working class suburbs. The Irish fleeing the Famine in the 1840s and later refugees from Eastern Europe, made their homes in Bradford. Nazi and Soviet persecution in the thirties and forties led to an influx of Poles, Ukranians, Hungarians, and Lithuanians. To fill the demands in the post-war labour market, migrants from the West Indies and South Asia worked in the textile and public transport industries. Initially they were young men who wanted to earn money then return home. However, many settled in Bradford permanently, later sending for their wives and families . In 1953 there were 350 Asian migrants in Bradford. By the 1961 Census there were 5000 from the Indian subcontinent living and working in the city. Little Horton with its large Victorian houses, accommodated many new arrivals. On the other side of the city, Manningham Lane, close to Valley Parade, had also been an area of substantial middle class housing, and was experiencing a similar transition. (3) At Manningham Mills, which had been the largest silk factory in the world, Samuel Cunliffe-Lister had employed 11000 workers in its prime. During World War 2 it had produced parachutes and khaki uniforms. Rows of working class houses had been built in its vicinity. Many Bradford City fans came from this area but by the 1950s supporters of both clubs were coming from all over the city and beyond.

It was still the age of steam railways, mills powered by coal, back to back terraced houses with outside toilets and no bathrooms with hot running water, public baths and wash houses, gas lamps, smog, horse drawn vehicles, whole communities employed in the same industries, poverty and poor health. Children still played in the streets. It was a common sight to see groups of them playing football using coats for goalposts, with the street lights enabling the first floodlight matches to take place as night descended. Many attended schools which had been established after 1870 thanks to the pioneering work of W. E. Forster, the Bradford M.P., and mill owner in Burley-in-Wharfedale. Teaching methods were very similar with an emphasis on the 3 Rs, rote learning, and the chanting of tables. Bradford has a proud history. (4) It had associations with liberalism and radicalism, through Chartism, and trade unionism. Following a strike in 1890-91 at Lister’s Mill, Manningham, the Independent Labour Party (the fore-runner of the modern Labour Party) was established in Bradford. It produced pioneers such as factory owners like John Wood and Titus Salt, and education reformers like W.E. Forster and Margaret McMillan. It was the birthplace of creative geniuses such as the writer J.B. Priestley and the composer, Delius.

Post-war Britain was undergoing profound economic and social changes. Austerity was giving way to affluence. So much so that the Prime Minister in 1957, Harold McMillan, claimed : “You’ve never had it so good”. The National Health Service with free medical care had been established in 1948. The Clean Air Act of 1956 tackled the long standing problem of air pollution (‘smog’) which in cities such as Bradford had been damaging people’s health. It had been one of the campaigns of Titus Salt over a century earlier and had forced him to move his factory and workers to the ‘model town’ of Saltaire.(5) The Housing Act of 1957 inspired the demolition of slum housing and the crumbling, sub-standard and unhealthy Victorian terraces. In their place, deprivation had been replaced by new housing estates and blocks of flats providing indoor bathrooms, modern kitchens and heating. In Bradford, the Ravenscliffe, Canterbury Ave., and Swaine House estates were considered ‘paradise’. Many heralded this ‘new world’ but gradually people began to moan that the old vitality and community spirit had been destroyed. Dissenting voices claimed that the Victorian heart of Bradford had been ripped out. Interesting buildings had been sacrificed on the altar of modernity. Kirkgate Market, Swan Arcade and the Mechanics Institute were demolished. To some, Victorian architecture had seemed ugly but the replacement Portland stone soon weathered into a drab grey. It had become a ‘material world’ of consumerism. By the late fifties, television sets, washing machines, cookers, and increased leisure time, including paid holidays, made life better. The modern teenagers with money in their pockets were following the latest trends in fashion, and expressing themselves through rock ’n’ roll. It was still claimed that people could go out and leave their doors unlocked and that there was no fear for children’s safety. Society was still basically safe and caring, and young football fans could feel protected by adults.

Bradford Park Avenue’s ground seemed crowded and bustling. At the beginning and end of the football season, there was usually a cricket match going on next to the football ground. In 1953, Yorkshire played the visiting Australians there. Crowds would gather prior to kick off, at half time and after the final whistle, to take in a few overs. My dad and I would join them until it was time to meet Les Horsman outside the dressing rooms with our complimentary tickets. He once took us into the changing room. My eyes filled up, not from the excitement of meeting the players, but because of the mixture of liniment and cigarette smoke in the atmosphere. Some players smoked before the game. Bill Deplidge sat me on the massage table, and passed round my new autograph book. It all seemed like a friendly, happy atmosphere, but how could a five year old know anything about the tensions and politics of a professional football club? Whatever the team talk was, I never found out because we had to leave to take our seats in the main stand.

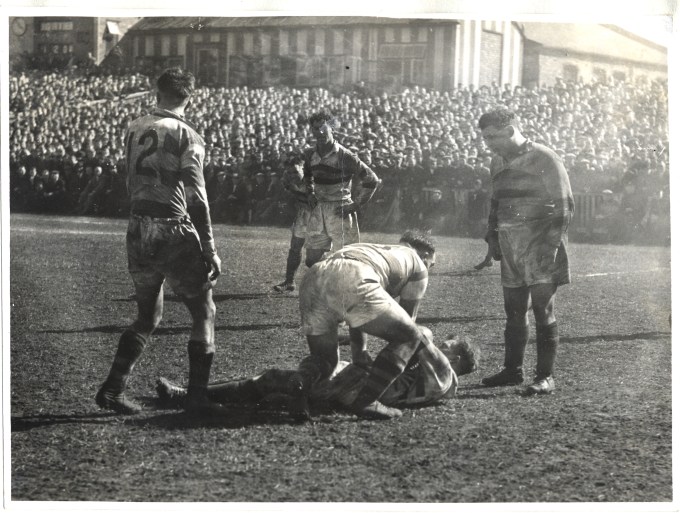

The scene outside appeared cold and grey. Clothing was not colourful. There may have been the odd black, amber and red scarf, and a football rattle, but very little else among the tightly packed, predominantly male spectators, many of whom wore flat caps. Little lads were often lifted over the turn-styles, and admitted free. The smog from generations of industrial pollution which seemed to hang above the valley, and blacken the nearby houses, was increased by the cigarette/pipe smoking crowd. I remember being impressed by the architecture of the football ground. Later on in the fifties when I was going down to Valley Parade, I was more impressed by the Bradford trolley buses, and Busby’s store, and felt the ground was not a patch on Avenue’s. The histories of the two clubs and their geographical locations had contributed to local rivalry.(6) It is still there to some degree. Recently I was talking to a veteran Bradford Park Avenue fan, who even after the club’s demise from the Football League in 1970, refused to ‘jump ship’ and switch allegiance to what he still called ‘the Manningham club’ down at ‘Wally Parade’, even during their brief flirtation with the Premier League. It may have been jealousy, but more likely good old fashioned loyalty. In the early fifties the impression was that Avenue fans felt superior because they had more success before the War, and they considered the area in which the club was situated ‘better’ than City’s Manningham Lane. By the late fifties with City in Division 3 and Avenue in the 4th Division, City supporters felt superior.

As a child brought up in the then mill village of Burley, my main passion in life was football. We didn’t have a television, even after the Queen’s Coronation of 1953 had given a boost to this new entertainment. The wireless in the corner of the room, sent out programmes from the BBC. ‘Listen With Mother’ at 1.45 pm, was the children’s favourite which was supposed to precede an afternoon nap when my mum could listen to ‘Woman’s Hour’. ‘Housewives Choice’ and ‘Music While You Work’ would accompany the housework, and at dinner time ‘Workers’ Playtime’, live from a factory somewhere in Britain, was popular, along with comedies such as ‘The Clithero Kid’, and ‘Educating Archie’ (which was remarkable because it featured a ventriloquist, Peter Brough with his dummy, Archie Andrews, on the radio!), and ‘The Goon Show’. There were plenty of variety shows such as ‘Have a Go’ with the Halifax presenter Wilfred Pickles, and ‘Billy Cotton’s Band Show’. On an evening, there were ‘scary programmes’ for adults such as ‘Dick Barton’ and ‘Journey into Space’. ‘Children’s Favourites’, was popular on a weekend, as was ‘Two Way Family Favourites’ on Sundays, fondly accompanied by the smell of roast beef and Yorkshire Pudding.

A special programme on Saturdays was ‘Sports Report’ presented by Raymond Glendenning until 1955, then Eamon Andrews. The theme tune ‘Out of the Blue’ probably brought most of the nation to a standstill at 5 o’clock, as the football results were read out. My dad would check his pools coupon hoping the treble chance would come up, and then we would be rich. Every week was the same: we didn’t become rich. I was then sent up the street to get ‘the Pink’, the Telegraph and Argus sport’s paper. After sweet rationing ended in 1952, I bought sweets for the family. I held them tightly in one hand and the pink rolled up in the other, and ran through the dark street whistling, which I thought was a way of warning off any potential Pink or sweet thief. Once home, my dad could read the football reports while me and my brother, Michael, shared the sweets with my mum.

I was captain of Burley Junior School’s football team in 1957. We played at the Rec on a full size pitch which meant it was difficult to reach the goal mouth from a corner kick. I later played for Burley Trojans on the same pitch which by then didn’t seem as dauntingly large. But the lasting memory was that the football, in the depth of winter, was like a soggy, heavy, medicine ball sticking in the churned up pitch. By summer it had turned suedey and misshapen, making it difficult to judge the bounce. But what was worst was constantly heading the soggy thing, especially the lace side. Our football boots were clumsy and brown. I would leave them a few days after a match for the mud to dry, then scrape them with a knife before dubbin them lovingly by hand. I often had to cut the laces off because it was impossible to undo the knots. I would purchase new, white, 72 inch long ones from Beever’s shoe shop at the end of Station Road, along with any replacement studs which my dad had shown me how to nail onto the soles using a hammer and last. When I bought my first pair of Pumas in 1965, football was suddenly transformed into a different game.

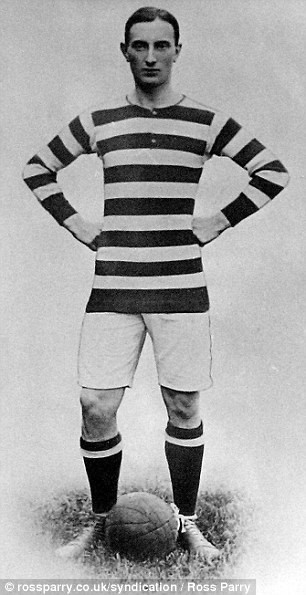

During the 1950s football heroes were local players, or Roy of the Rovers in the Tiger comic. (7) We were not subjected to television coverage and media hype, and we followed our local team not some top successful club supported from an armchair. My hero was Les Horsman who not only played for Bradford Park Avenue, but in summer captained Idle cricket team in the Bradford League. He played 239 games between 1946 and 1953, scoring 12 goals before being transferred to Halifax Town with whom he played 120 times and scored 8 goals. This meant my dad and I started watching Town for a bit. I detested the long journey which included changing buses to Halifax. The Hebble bus always seemed crowded and hot, and I was inevitably pressed up against the round heater at the front so an elderly man, or woman, could sit down. It’s a wonder I never passed out. We would meet Les at the Shay before the match.

I particularly remember a game against Hull City for whom Stan Mortenson was playing after his Blackpool and England days, and his outstanding performance in the 1953 F.A. Cup Final. After retiring from professional football in 1957, Les had a paper shop at the end of Iron Row in Burley, and I delivered papers for him. I would sometimes go into his living room at the back of the shop where I used to stare at his trophy cabinet containing medals and cups from his football and cricket careers. I would dream of being a footballer but advice from Les changed my life. He told me that he had always loved playing football but he didn’t make much money, and without qualifications or a trade, he supported his family by running a shop. He suggested that I should use my educational opportunities and interest in sport to train as a PE teacher.

I did take his advice and became a teacher, not PE but History, though I did coach school football teams. I continued to play football as an ‘amateur’ for fun. Conversations with him revealed there was a different side to a footballer’s life, especially in the lower divisions, that was not so glamorous.

The former Bradford Park Avenue player, Len Shackleton, who went on to play for Sunderland and England, wrote a controversial autobiography, ‘Clown Prince of Soccer’, which reflected on what it was like to be a professional footballer in the 1950s. Avenue fans still raved about Shacks who had been transferred to Newcastle for £13000 in 1947, the year I was born. He scored six goals on his debut against Newport County. Les Horsman had played alongside him and once told me he was dazzled by his skills. Len was transferred to Sunderland in 1948 for £20,050, which was a record fee at the time. Colin Bell, the great Manchester City and England midfielder, once described him as “a magician with the ball – – – who could make opponents look foolish with his tantalising tricks.” (8) Other professionals, such as Stan Mortenson and Tommy Docherty, and journalists, gave him high praise, but he was not in favour with ‘the establishment’. This is why, despite his outstanding ability, he played only five times for England. He was born and bred in Bradford into a working class family who supported Bradford City. He attended Carlton High School and was capped for England Schoolboys. At fifteen he signed as an amateur with Avenue, but then had a spell with Arsenal before World War 2, failing to make the grade. He returned to Avenue and signed professionally in 1939. On Christmas Day, 1940 he played for Bradford Park Avenue against Leeds in the morning, at Elland Road, and guested for Bradford City at Huddersfield in the afternoon. He was always forthright, and criticised the professional game.

This Bradford lad published his critical autobiography in 1955.(9) In it we get some idea of what was wrong with English football. Chapter 9, entitled ‘The Average Director’s Knowledge of Football’, was deliberately left blank in accordance with Shackleton’s wishes. He believed directors treated professional players like serfs or slaves. His views were largely based on his experiences at Avenue and Newcastle, supported by fellow professional’s opinions.

He claimed he was barracked by a section of Avenue supporters. “Invariably when a player holds the ball in an effort to do something intelligent with it – rather than passing the buck to a team mate –he comes in for advice from the knowledgeable ones on the terraces. Ball players – – must expect to antagonise the ‘get rid of it’ faction while trying to inject fresh ideas into the bloodstream of modern mass-production soccer.’ This treatment influenced his decision to leave Park Avenue. Stanley Matthews commenting on the transfer to Newcastle, argued it was “another proof of the harm unsporting spectators can do to players and clubs.”

Players’ futures were in the hands of directors and some were deliberately obstructive when it came to transfers. He was critical of the running of the Park Avenue club. He was not consulted about moving to Newcastle until the deal was done. Avenue, and City, sold players with great potential, to balance the books. Derek Kevan who also became an England international with West Brom, Billy Elliott, another international who went to Sunderland, and Ron Greenwood a future West Ham and England manager, were sold for financial reasons, and this policy continued throughout the fifties. Bradford City sold Derek Hawksworth, John McCole and Derek Stokes much to the anger of the City supporters. The selling of talent affected the success of the Bradford clubs. (10)

Shackleton’s fresh start with what he considered a great club could have established him at Newcastle for the rest of his career, if the club had been run more efficiently. Consequently, he left for rivals, Sunderland, in 1948, where he became a hero.

Shackleton was scathing about the professional footballers’ contracts which he said were one-sided. Questions were even asked in the House of Commons amidst public indignation. He urged other players to speak out against it as they were no better than professional puppets dancing to directors’ tunes. Football was still largely a working class sport, and professional footballers’ wages were not that much more than a working man’s. There was a maximum wage. In 1951 it was £14 a week which was raised to £15 in 1953, £17 in 1957, and £20 in 1958. By 1960 the gap between a footballer’s wage and an industrial worker’s wage was £5. Shackleton was critical of this wage structure.

He wrote that a footballer appears to have “a pretty good life with a possible £15 a week wage”, but many are the victims of the whims of directors, who could evict them from a ‘club house’ when they dispensed with their services, and the pretty good life was over before the age of forty, providing it was not curtailed prematurely through injury. The average playing life was seven years, and the average retirement age was 35, so that in the prime of life he could be jobless, and homeless with no training or qualification for a trade or profession. Few of them made it into management or coaching so it could be a depressing end to a career for the player and his family with no security. When they signed for a professional League club they were tied for life or until the contract was terminated without notice by the manager or directors.

Shackleton claimed that no other civil employment placed such restrictions on the movement of individuals, while retaining the power to dismiss them. They did not have the freedom to better themselves. Tom Finney, the Preston and England winger, was told that he would be a rich man for life if he spent five years playing in Italy, but Preston would not dream of allowing him to go. He supplemented his income during his playing days by establishing a plumbing business. Wilf Mannion, the Middlesbrough international, was offered a contract with Juventus who were prepared to put £15,000 into his bank account, but Middlesbrough stood in his way. He also claimed he had been approached by a Turkish club, and could have earned much more than he could have dreamed of in English football. Some players such as John Charles successfully escaped as he did when he left Leeds United for Juventus. He was very popular over there, a popularity which continued for the rest of his life, and he enjoyed a lifestyle unthinkable in England at the time. In 1960 a campaign led by Jimmy Hill, President of the Professional Footballers Association, threatened strike action if the maximum wage was not abolished. This was accomplished in 1961 and in time, players could negotiate new improved wage levels. Some had been arguing they were like entertainers playing in front of large crowds and deserved a fair share of the income. Johnny Haynes of Fulham and England became the first £100 a week footballer.

Professional footballers at all levels loved the game. Billy Wright, the Wolves and England captain, claimed he would have played for England for nothing, the England cap was enough. Nat Lofthouse the Bolton and England centre forward, regarded it a pleasure to play. Talking to former players it was obvious that football gave them a passion throughout life. Jeff Nundy signed for Huddersfield Town as a part-time professional for £4 a week, but he was not retained when Bill Shankly took over. He went to Bradford City, managed by Peter Jackson during the 1955-6 season, and eventually turned full-time. His basic weekly wage was £11 with a bonus of £2 for a win, and £1 for a draw. He had been an apprentice engineer, and some players, like Bobby Webb, remained part-time because they were better off. A part-timer trained Tuesday and Thursday evening.

Some players in the 1950s increased their incomes through commercial ventures. Denis Compton of Arsenal and England, was known as ‘the Brylcreem Boy’ because he advertised the product. He was a cavalier figure who was one of the few sportsmen to become a double international when he played for England at football and cricket. He was a working class hero who earned a reputation as a playboy. He could have fallen foul of the Establishment but was likeable and talented, so he got away with it. He played in the FA Cup winning Arsenal team of 1950, alongside his brother Leslie, who also played cricket with him for Middlesex. In the Liverpool team that day was the Gloucestershire county cricketer, Phil Taylor. Incidentally, Denis was so exhausted in the final that at half time he had to be revived with a glass of brandy.(11) He had to retire from football because of a knee injury, but continued to play cricket.

Stanley Matthews endorsed a new style of football boots, and Craven ‘A’ cigarettes. He was criticised for promoting cigarettes at a time when scientists were establishing a link between smoking and lung cancer. For local Bradford footballers there were few commercial opportunities. For many players life after football meant running a pub or shop, or gaining employment in a local factory. Some, however successful as a player, struggled financially.

During the seventies I helped organise a testimonial match and wrote the programme notes for the legendry England centre forward, Tommy Lawton, who retired in the 1950s. He had fallen on hard times. He was highly respected by fellow professionals. It was a privilege to meet and chat with such a fine gentleman but sad to see how his life had turned out. He was proud to have played with outstanding players, and paid for it too. He felt he was lucky as many supporters were not well off and some were unemployed. He had to dress correctly, and not let the club down. Accommodation was provided for some, and a free lunch after training.

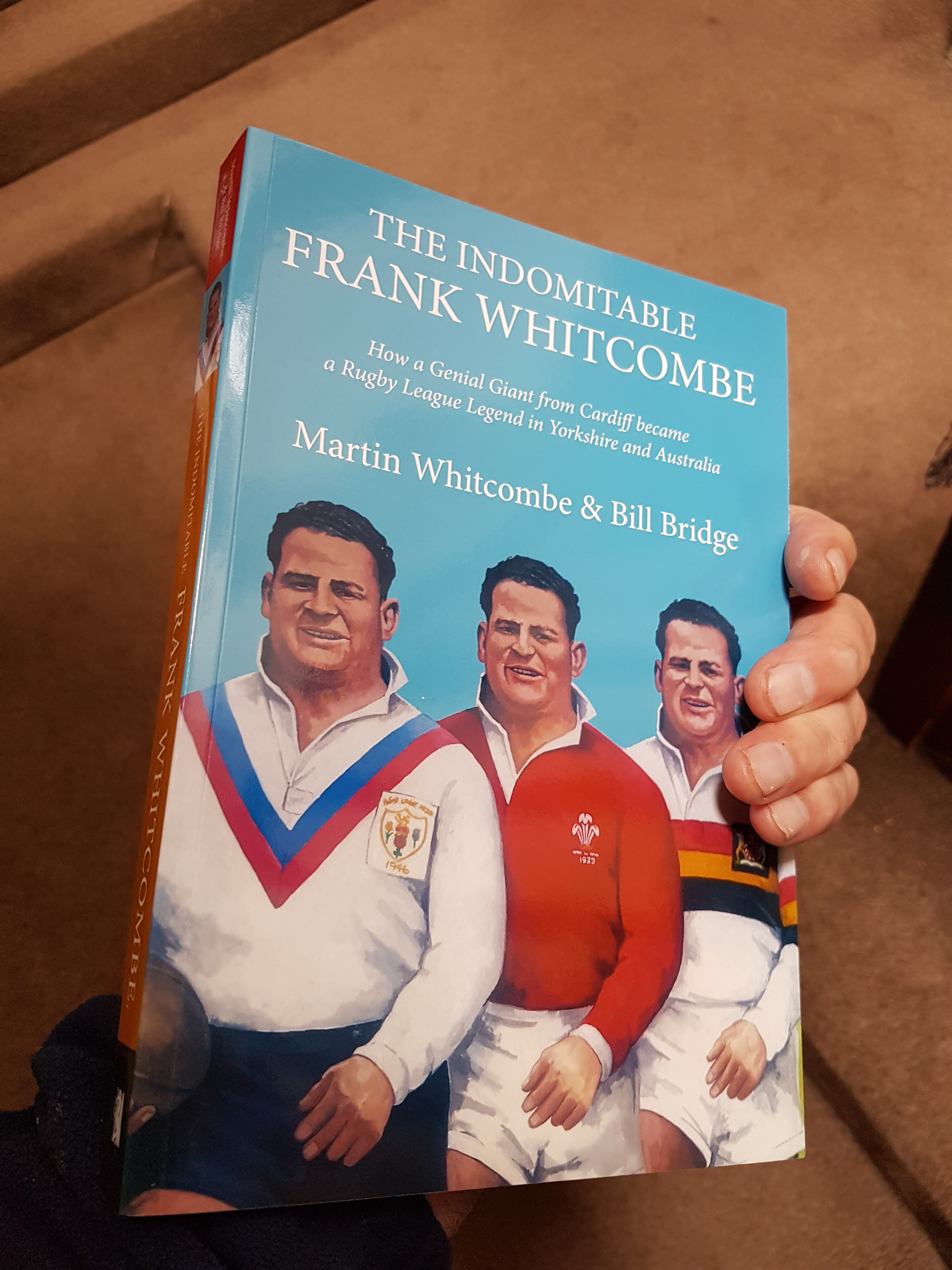

Players took a cut if they were dropped or injured. In summer wages were lower; in 1953 it was £5. It was possible for footballers to play cricket because the season was shorter than it is today. Les Horsman captained the successful Idle cricket team in the Bradford League. My dad took me to see him play. On one occasion he was out for a duck. As he came off his excuse was that he had a hole in his bat. He was such a hero to me that I believed him. Ken Taylor the Huddersfield Town player who finished his career with Avenue played for Yorkshire and England. Willie Watson, was a left handed batsman for Yorkshire and England in the fifties, and a cultured wing half, starting with Huddersfield before the War, and Sunderland and England during the fifties. He finished his career with Halifax Town in 1956 as player-manager. He managed Town between 1964 and 1966, before moving to Bradford City from 1966 to 1968. (12)

The English game had been criticised for being too insular and aloof. It was the birth-place of soccer and was responsible for spreading it throughout the world. (13) But England refused to participate in the World Cup when it was established in 1930, and English clubs were discouraged from playing foreign teams. There were disagreements between the Football Association and the Football League. The attitude seemed to be that we had nothing to learn from others, but during the 1950s the face of football began to change.

England entered the World Cup for the first time in 1950, though unsuccessfully, and it became obvious that we could learn from others. The Football League did remain the leading example of the domestic game in the world, but in the ‘rock ‘n’ roll’ years of the later fifties, foreign influence was to have a profound effect on English football not only at international level but throughout the four divisions of the Football League. How far it reached out to Bradford is open to question.

Bradford City did play in France in 1951 against Mazamet to mark the wool town’s Centenary and won 2-1. In 1954 they went on a pre-season tour of Holland. In the 1955-6 season the European Cup was introduced with Real Madrid the winners. By now European football was on the rise with Spain and Italy showing the way. The World Cup in 1958 brought Pele and Brazil to the fore front. Hungary’s arrival in England in 1953 emphasised how outdated had become the tactics and training methods in English football. England were thumped 6-3 and lessons had to be learned. It was the first time England had been beaten at home.

On the Continent ball control was taken more seriously and emphasised from a very young age. Mastery of the ball helped to boost a player’s self confidence and belief in his ability. It allowed more options on the field so that tactically teams could be more effective. Shackleton held this opinion in his book, and others urged changes in coaching methods. Coaches and managers needed to be of a higher calibre and have the ability to implement new ideas.

I remember going down to watch City train at Valley Parade in 1958. Training seemed to consist of running down the pitch and up and down the terracing. I never saw a ball produced all the time I was there. This childhood memory has been confirmed by former City players. It was believed that if they were starved of the ball during the week, they would be hungry on match days. So ‘continental ideas’ didn’t appear to have travelled down to Valley Parade, and practicing ball skills seemed to be off the agenda, which may have inhibited success. However, the physical training made them one of the fittest sides in the League.

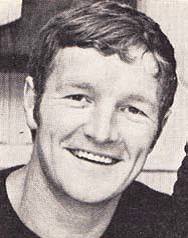

Leaning on a brush, having a break from sweeping the Kop was a young apprentice. He was friendly and I got talking to him. He said he wanted to be training ‘down there’ and playing in the first team. This young lad turned out to be Trevor Hockey who became a favourite and a Welsh international. He was from Keighley playing amateur football when City spotted him. He made his debut during the 1959-60 season and was then sold to Nottingham Forest during the 1961-2 season. He had a nomadic career playing for Newcastle, Sheffield United, Birmingham, Aston Villa and Norwich. He made almost 600 appearances, but tragically died at the age of 43.

Jeff Suddards was a local hero at Bradford Park Avenue. He attended Tyersal School, and signed in 1950. During the fifties, Avenue had seven managers which didn’t help to develop continuity and consistency, and could have contributed to lack of success. Suddards played under all of them. He claimed that the club went downhill when “they got directors who were small men with little knowledge of the game, and they would not pay for players of the quality we needed.” He had similar views to Shackleton about the importance of ball skills. (8) “The trouble at Avenue was we had players who couldn’t control the ball properly and because of the wage system which meant your money was halved if you were dropped into the reserves, there were some who would ‘hide’ rather than risk injury. Some continued to play despite injury.

There was little in the way of medical treatment at the club. In the late fifties, a heat lamp was purchased at Valley Parade to treat muscle injuries. Key players’ careers were terminated, some prematurely, due to injuries which today would be repaired.

Ron Greenwood, writing in his autobiography, (15) revealed that at Avenue, the manager, Fred Emery, only saw players before matches. No one talked tactics and they had to work things out as the game progressed. Jeff Nundy who played for City from 1955 to 1961 said it was the same at Valley Parade. He recalled that before games, the trainer, Jock Robertson, would come round with a bottle of whisky which the players sniffed and rubbed their lips around the bottleneck. The game was basically simpler than it is today with each player knowing what their role was. Players such as Reid, Stokes and Robb had flare, and the idea was to get the ball forward as quickly as possible. John McCole was a very confident, prolific goal scoring centre forward, and if he missed a chance, he just shrugged it off, believing he would score next time. Having confidence is important in achieving success, and lack of confidence in a footballer shows up on the pitch. Here coaches and managers play a key role, but this seemed to be absent at both Bradford clubs. Good players who shone in the reserves, like Jeff Nundy, found it difficult to make the transition into the first team. Allan Devanney told me a few days before he tragically died in Otley, that he had a similar experience at City, especially when he replaced Derek Stokes, the fans’ favourite. The pressure affected his nerves and performance, and ended his career.

The post-war period up to 1958 in some ways was ‘a golden age’ for smaller clubs, but the Bradford teams were often haunted by financial problems. Ivor Powell was appointed City’s player-manager in 1952 with the brief that he had to cut expenses to the bone. He reduced wages by 40% and travel costs by 15% in one season. A public appeal was launched in the same year to raise £20000 for new players, but this was unsuccessful. One of the first to be signed was Brian Close the Yorkshire and England cricketer, who played nine games before injury ended his football career. Players continued to be sold and the income went towards ground improvements. Directors were local businessmen who were reluctant to put their hands in their pockets. The Midland Road stand at Valley Parade was considered unsafe back in 1949. It was cut into the slope of the hillside and its foundations were unstable. It was sold to Berwick Rangers for £450, and a new stand was opened in 1954. (16)

But alas, this was soon considered unsafe and demolished in 1960. In 1954 floodlights were installed on telegraph poles along each side of the ground.

Avenue’s floodlights were switched on in October 1961 for a game against the Czech national side. They were on 95 foot high pylons but were brought down in gale force winds the following February. Floodlit football allowed mid-week games, and saw the introduction of the white ball. But results were mediocre, and Powell was sacked in 1955 with City in the bottom four. Peter Jackson was appointed, and he was told to develop home grown talent. The club had a policy of not signing anybody over the age of thirty, and in 1956 had the youngest team in Third Division North. The wage bill was also the lowest since 1948. They finished the 1957-8 season in third place. It was rumoured that the directors were worried they might achieve promotion and this would increase financial costs in Division 2. They didn’t achieve promotion, but they qualified for the new Third Division after the Football League decided on restructuring by creating the Third and Fourth Divisions. Avenue finished in the bottom half and so were relegated into Division 4. (17)

In the early fifties, Stanley Waddilove was Avenue’s Chairman. For him the club was his hobby but he was reluctant to invest. He was a dominant figure who was quick to criticise. He insisted that unless crowds improved, players would continue to be transferred. (Bradford Telegraph and Argus, December 1st, 1949.) (18) Lack of success was repeatedly blamed on selling the best players. By 1955 Avenue’s finances were even worse with debts of £35000. Waddilove insisted that the directors would decide which players were to be transferred or bought. This interference was cited as a reason why Bill Shankly was not appointed as the new manager; he was not prepared to accept board control over team matters. (6) In 1955 the financial situation grew worse.

Manager Kirkman was sacked, and Waddilove resigned. Reginald Kellett took over management on a temporary basis for the 1955-6 season and it was his ceaseless efforts and youth policy which prevented the club going out of business, according to the Telegraph and Argus (Feb. 3rd., 1960.) (19)

By 1957-8, the post-war soccer boom was over. The decline in attendances was around 20% compared with the peak of 1948-9. Though City’s crowds were slightly higher, both clubs were suffering due to performances on the pitch, and significant social changes which were highlighted in the News Chronicle Survey into ‘The State of the Game in 1959-60’. (20) Many believed television was keeping people away from football matches. Sir Stanley Rous, secretary of the Football Association, noted that television was a factor but also added the availability of hire purchase and competition from other sports. The game needed better facilities, more input at youth level, and the restructuring of league and cup competitions. In some parts of the country there had been a decline in junior leagues. The Bradford Red Triangle went down from 28 to 12 clubs. The game had to be remarketed to appeal to spectators. The News Chronicle claimed young people turned away from football because they had other interests. “This is the money to burn generation, and that money is not being spent on football”. Instead it was bringing “wealth to the gramophone-record industry” and “the manufacturers of exotic suits and shoes”, and motor bikes. (News Chronicle, 10 February, 1960). (21) The Secretary of the Bradford Red Triangle League argued that teenagers were more interested in rock ‘n’ roll, not football. It was difficult to attract players and they wanted everything laid on. Another factor that needed addressing was the decline of playing fields due to the house building boom.

Social changes were to weaken local identifications and loyalties. Whereas the increase in the number of motor cars enabled fans to travel to more away games, they also allowed them the option of watching other teams such as Burnley, Huddersfield Town and Leeds United, playing in higher divisions against more attractive opposition.

It was the considered opinion that the Avenue had a better ground in a better location. In comparison Valley Parade was shabby. Discussions about merging had taken place during the fifties but to no avail, inhibited largely by ‘tribal rivalry’ and historical loyalties. Derby games between City and Avenue continued to be the highlights, with City generally having the upper hand. There were sixteen derbies during the fifties with City winning six and Avenue five. They came to an end when Avenue were relegated to the 4th. Division in 1958. Before that gates up to 20000 could be expected. (22) There was a tremendous atmosphere and intensity, though no hooliganism in non-segregated crowds. There was much more rivalry between the fans rather than the players, though ‘derbies’ were very competitive, with players challenging harder for the ball, and passing comments to each other. After all, there was pride at stake, and the honour of being ‘top dog’, until the next encounter.

It was customary for spectators from both teams to mix together on the terraces, though there was the practice of fans swapping ends so they could be behind the goal their team was attacking. For the FA Cup match against Everton in the third round, 1959-60, which City won, 3-0, with goals from David Jackson, Reid and Stokes, I was packed in the Bradford End in a crowd of 23550. I was intrigued by the Scouser accent and sense of humour. When they started urinating on the terraces, I thought this is what it must be like in the First Division. Mind you, the toilet provision at Valley Parade was very primitive. Before 1985, there was only one female toilet in the entire ground.

At half time a local brass band, often Hammonds Sauce Band, would entertain the crowd. Tunes by Sousa were popular including ‘Liberty Bell’ which later became associated with Monty Python.

The players’ changing rooms were also diabolical. They were situated in the end house on Burlington Terrace and were over crowded and cold with water all over the floor. The players ran out through a tunnel by the corner of the Kop. It was dingy and slippery and infested with cockroaches. The teams came out gingerly so as not to go over on their ankles. Jeff Nundy remembers that the kit was immaculately set out and neatly ironed. After the game their boots were hosed down and left to dry for the next time they came in for training. A number of players didn’t have cars and mingled with the supporters as they walked down Manningham Lane. Jeff Nundy had to catch two buses. I remember waiting for the Ilkley bus after a game and seeing Jim Lawlor standing at the Keighley bus stop. I met Jim and Tom Hallett at a Bantam’s Museum function and they agreed it was a far cry from the experiences of today’s players. Jeff Suddards recalled when he started playing for the Avenue in 1950, they would meet up before the game at the Victoria Hotel for a few games of snooker and lunch of chicken and toast before being taken to the ground in taxis which slowly weaved their way through the crowds walking up from town. Park Avenue was a beautiful ground to play on and the facilities were better than City’s, and the crowds liked to go there. Teams tended to travel to away games on the same day, unless it was a very long journey such as Bournemouth, and Plymouth when they would stay in a hotel. The City team would meet at the ground, and on the way they stopped for a light lunch which Jeff Nundy remembered was usually egg on toast. There was a good team spirit. Some players played cards on the coach or just chatted. John McCole and Bobby Webb were jokers and George Mulholland had a dry sense of humour, so there was plenty of fun.

After training some City players went for a game of snooker, others went to a café in Bradford Market for lunch. But despite good team spirit successive teams failed to produce the results which would bring promotion. A winning team attracts bigger crowds, and puts the club on a stronger financial footing.

Success in the FA Cup,1959-60, created a feeling of optimism that City were at last on the road to success. After disposing of Everton in the third round they went on in the fifth to face Burnley who became First Division Champions at the end of the season. The all-ticket crowd of 26227 got behind the team, and despite City leading through Webb and Stokes, two late goals by Burnley, who found it difficult to play their short passing game on the Valley Parade mud, led to a replay at Turf Moor in front of around 53000 people. (23)I was in that crowd with my dad and Les Horsman, and despite being lifted down to the front, I don’t remember seeing much. I do remember the disappointment at losing 5-0, and going down with flu a few days later. The cup run brought in much valuable income, but this was not spent on players.

The directors spent £14000 on second hand floodlights from West Ham in March 1960, then work started on covering and improving the Bradford End, giving it a capacity of 3500. New club rooms, offices and changing rooms were provided. But star players continued to be sold. McCole went to Leeds, Stokes to Huddersfield and Hockey to Nottingham Forest. So the anticipated success at the end of the fifties turned to despair. The following season City were relegated.

The fortunes of both Bradford clubs had been on the wane throughout the fifties.(24) In 1949 City had finished bottom of Division Three North and had to apply for re-election. The directors embarrassingly had to write to the other clubs for support. Avenue had to seek re-election in 1956. In fact from the 1949-50 season to 1957-8, a Bradford club finished in the bottom five of Division 3 North on five occasions.(19) In 1950-51, Avenue’s average home gates were 12300, and City’s 12500. By the end of the 1959-60 season Avenue’s crowds had plummeted to 6500, though City faired better with 10200. There was still the loyal core of fans but this was diminishing.

Disillusionment and cynicism were creeping in.

So why were the fifties ‘a decade to forget’? Blame has been heaped on directors and management for their lack of ambition and abilities. The clubs had players with flare but they were usually sold to solve financial problems.

This hand to mouth existence made forward planning and establishing a strong squad very difficult. The structure of players wages and conditions affected the professional game, and particularly lower clubs like City and Avenue. Injuries and low confidence, despite what appeared to be a good team spirit, seemed to hinder success. Training methods and lack of tactics kept them in the doldrums. Though some critics believed the two clubs should have pooled their resources and merged, a city the size of Bradford should have been able to sustain two football league teams. The potential support was there as history proved, but perhaps the cultural, social and economic changes during the fifties were inhibiting positive development. Failure on the pitch put both clubs on the slippery slope. (25)

Throughout the country virtually every city and town had a football league club which meant something to the community. Bradford was no exception.

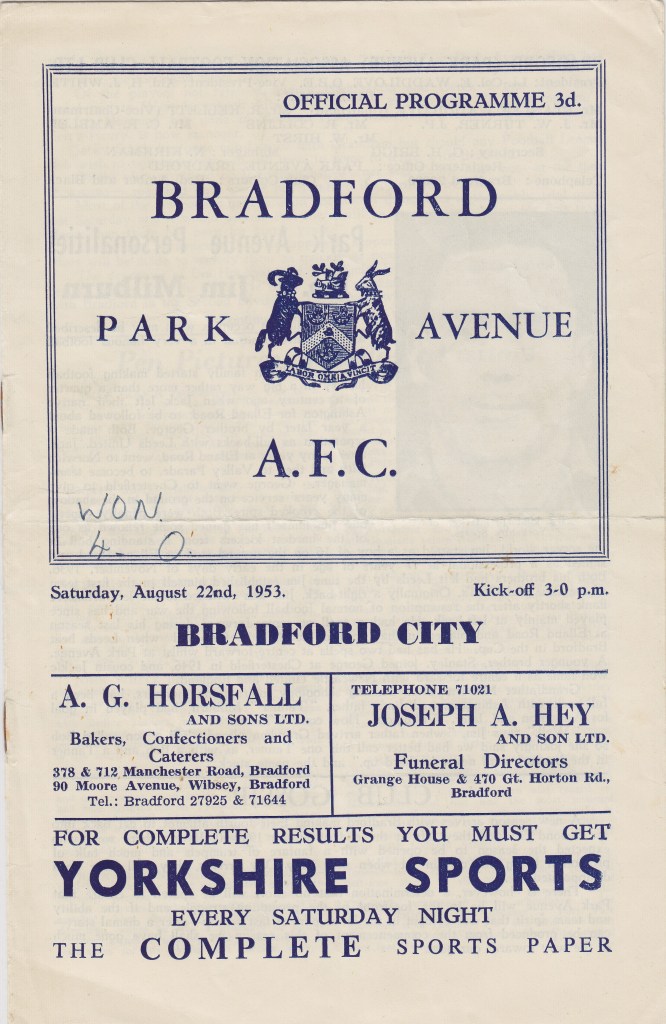

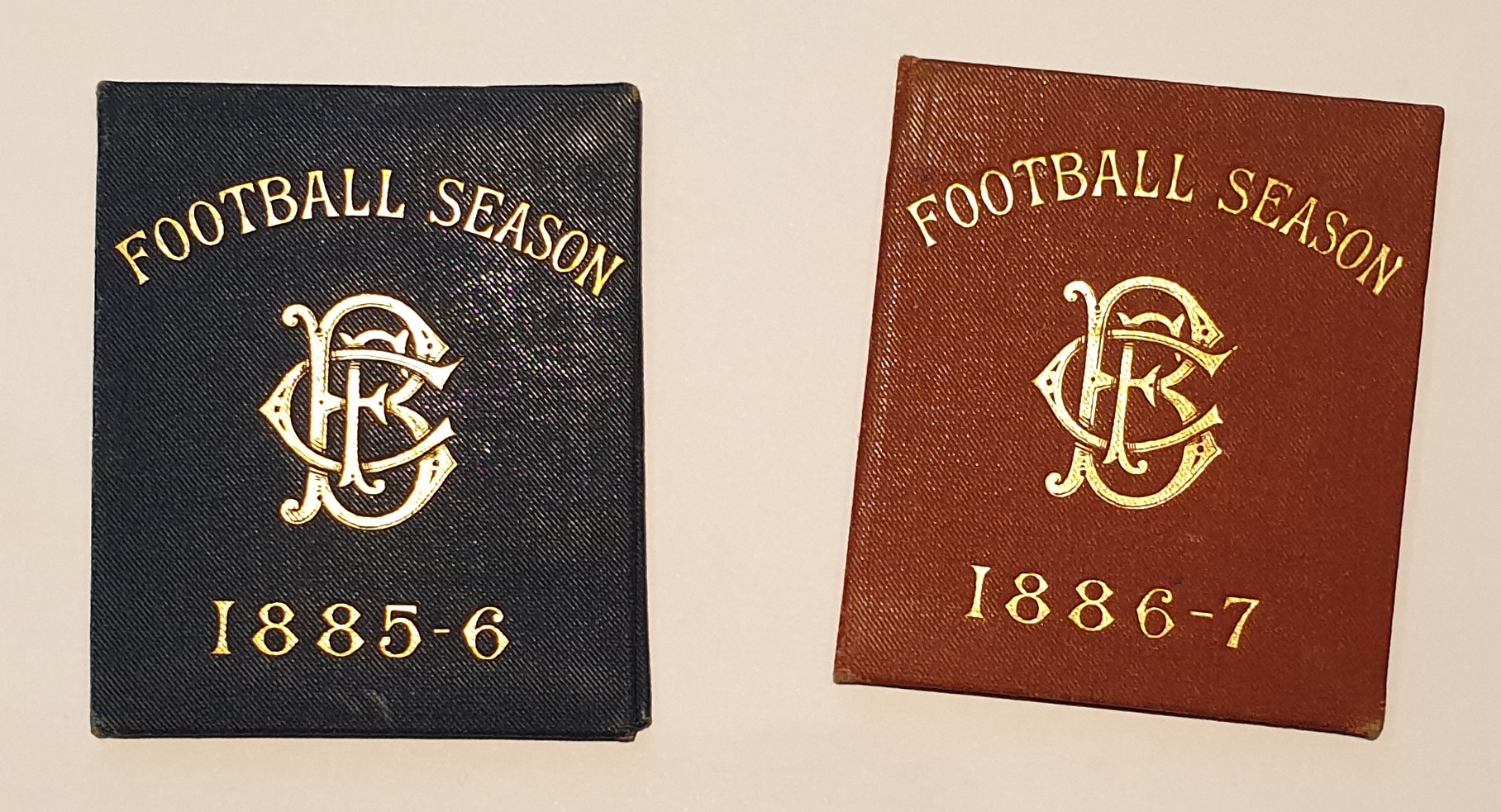

Several clubs struggled on and off the pitch in the fifties, and they too may have considered it ‘a decade to forget’. However, there is more to football than football. In the fifties football was still a working class sport, played and watched largely by the working classes. Nowhere else in the world would you find such interest and attendances at the lower level, and this helps to make English football ‘a rich game’. It is not ‘a decade to forget’ if it is the decade when you begin to watch your local team. This can not be erased from the heart and mind. It lays the foundation for a life-long passion, treasured in the programmes, autographs, photographs, and newspaper cuttings from that time. (26) It ignites a flame which gives hope that though there might be disappointments and sorrow ahead, there will also be joy and success.

References.

1. Telegraph and Argus March 20th, 1950.

2. Richardson, C, A Geography of Bradford, University of Bradford, 1976.

3. Sheeran, G. The Buildings of Bradford: An Illustrated Architectural History, Tempus, 2005.

4. Firth, G, A History of Bradford, Phillemore, 1997.

5. Reynolds, J. The Great Paternalist: Titus Salt and the Growth of 19th Century Bradford, Maurice- Temple Smith, 1983.

6. Hartley, M and Clapham, T., The Avenue: A Pictorial History and Record of Bradford Park Avenue AFC, Temple Nostalgia Press, 1987.

7. Riches, A., Football’s Comic Book Heroes, Mainstream, 2004.

8. Harvey, M., and Clapham, T. All About Avenue: The Definitive Bradford Park Avenue AFC, Tony Brown, 2004.

9. Shackleton, L., Clown Prince of Soccer, Nicholas Kay, 1955.

10. Markham, D. and Sutton, L., The Bradford City Story: The Pain and the Glory, Breedon, 2006.

11. Lloyd, G. and Holt, N., The FA Cup: The Complete Story, Aurum, 2005.

12. Watson, W., Double International, Stanley Paul, 1956.

13. Walvin, J., The People’s Game, Mainstream Publishing, 1994.

14. Butler, B., The Football League: The Official Illustrated History, Blitz Editions, 1993.

15. Greenwood, R., Yours Sincerely, CollinsWillow, 1984.

16. Pendleton, D. and Dewhirst, J., Along the Midland Road, Bradford City AFC, 1997.

17. Gillan, D.R., Dewhirst, J., Clapham, T., and Mellor, K., Of Boars and Bantams: A Pictorial History and Club Record of Bradford City AFC, Temple Publishing, 1988.

18. Telegraph and Argus, Dec. 1st., 1949.

19. Telegraph and Argus, Feb. 3rd., 1960.

20. Nannstad, I., The State of the Game, 1959-60: News Chronicle Survey, Soccer History, 32, 2014.

21. News Chronicle Feb. 10th., 1960.

22. Pendleton, D., Paraders: 125 Year History of Valley Parade, Bantamspast, 2010.

23. Frost, T., Bradford City: A Complete Record 1903-1988, Breedon Books, 1988.

24. Dewhirst, J., The Fall of the Bantams, City Gent, 86, 2000.

25. Arnold, T., A Game That Would Pay, Gerald Duckworth, 1988.

25. Dewhirst, J., A History of Bradford City AFC in Objects, Bantamspast, 2014.

Acknowledgements

The staff of the Local History Department at Bradford Central Library.

Mick Lamb, Bradford City AFC.

The footballers of Bradford City and Bradford Park Avenue who played during the 1950s.

Jeff Nundy for taking the time to talk to me about his footballing experiences.

The late Les Horsman for his inspiration.

My dad for taking me to my first football matches.

All those who collectively helped to make my childhood in the 1950s a decade to remember.