A reputation of failure?

One can be forgiven the observation that the modern history of Bradford football – by which I mean rugby and soccer – has been dominated by financial failure and disaster. In the last hundred years there has been a financial scare involving at least one of the three professional clubs – City, Avenue or Northern – in each decade. It is a truly astonishing record; quite literally there have been more crisis appeals and fund-raising initiatives than league or cup triumphs. And only in the last few weeks have we heard news about winding-up petitions leading to speculation about the solvency and future of Bradford Bulls RLFC.

Since the start of this century there have been crises at both Valley Parade and Odsal. Indeed, neither Bradford City nor Bradford Bulls are strangers to administration procedures. In the space of twenty years, the city’s three senior clubs all succumbed to insolvency. In 1964, the former Bradford Northern club was dissolved and went out of existence for twelve months. Ten years after that came the liquidation of Bradford (Park Avenue) AFC and the following decade saw the collapse of Bradford City in 1983.

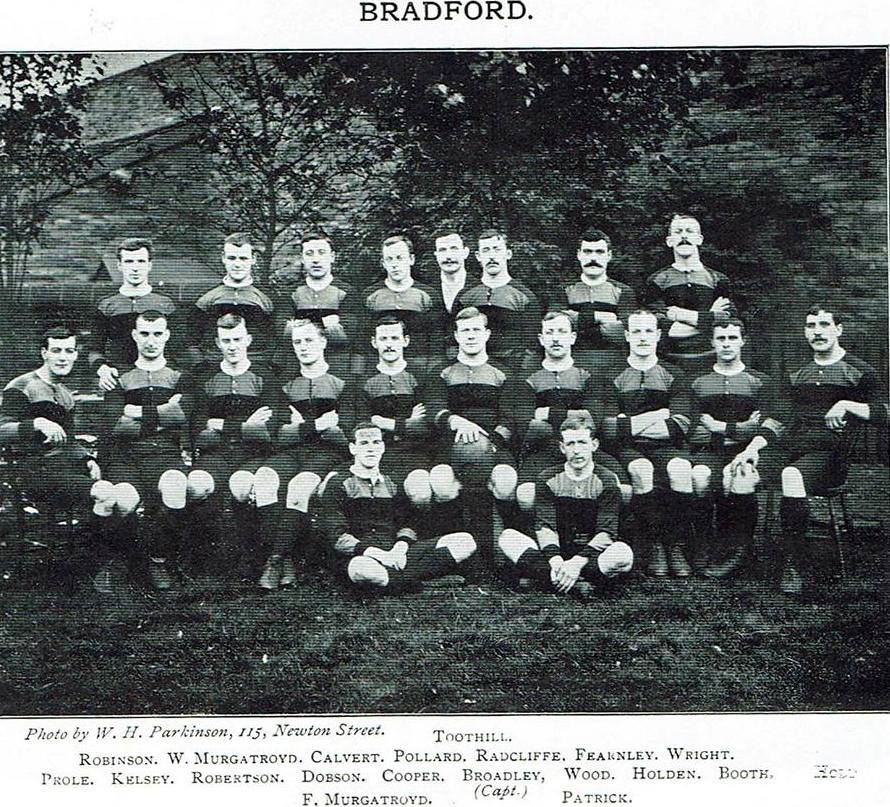

Yet if Bradford has the unwanted reputation as the city in which professional sport has been more prone to failure, consider the fact that in the forty years preceding World War One it was considered a centre of sporting excellence and a pioneering sports town in West Yorkshire. Its cricket club – formed in 1836 – had a reputation for ‘pluck’ and was among the leading sides in Yorkshire. Bradford FC was the oldest rugby club in the county with its origins dating to 1863 and at the beginning of the 1890s was regarded as one of the leading sides in the country, consistently boasting at least a couple of players in the England XV. Its two clubs – Bradford FC and Manningham FC – were founder members of the Northern Union breakaway in 1895 and the Paraders were inaugural champions in 1896. With the abandonment of rugby by Manningham FC in 1903, Bradford City was the first soccer club in West Yorkshire, promoted to Division One five years later and winning the FA Cup three years after that.

It was not just footballing activity that enhanced Bradford’s reputation. Bradfordians were known for their capability and enthusiasm in other sports that ranged from cricket to cycling, gymnastics and for that matter, chess. All told the city became known for the sheer vibrancy of activity, exemplified by the popularity of grass roots soccer under the umbrella of the Bradford & District FA at the beginning of the twentieth century. The success of the Bradford Cricket League after 1903 is another example of the enthusiasm for sport in the area measured by levels of participation as well as spectator attendance at local games.

Bradford was also known for the fact that its clubs were recognised for pioneering the commercialisation of sport. The original Bradford Cricket Club had been the first in this direction during the 1850s and 1860s but it was the opening of Park Avenue for cricket and football in 1880 that took it to a new level. By 1890 Bradford FC was reputedly the richest sports club in England, the subject of tax investigations in 1893.

Why did it go wrong?

The success of Bradford sport prior to World War One is in contrast to the general malaise of the city’s professional clubs that existed during the next 75 years. Ironically the one club which enjoyed sustained success during this period was the – amateur – Rugby Union side, Bradford RFC between 1919 and the mid-1930s.

The explanation for the barren decades of the twentieth century was not because the people of Bradford were uninterested in sport. Far from it. Failure came principally because sporting efforts and resources in the district were fragmented between four competing clubs – Bradford City and Bradford Park Avenue in the Football League and then Bradford Northern RLFC and Bradford RFC participating in the two rugby codes. Little wonder that the city struggled to support them all. Notwithstanding that financial collapse of City, Avenue and Northern arose in the first instance from the failure of financial management in those clubs, the odds for success were ultimately stacked against them.

The emergence of Manningham FC had led people to ask in the early 1880s whether Bradford could support two clubs and it was the success of Manningham in cup competition that persuaded people that there was room for more than Bradford FC. Indeed, it was this confidence that led to the commitment to develop Valley Parade in 1886. Twenty years later people were no longer convinced and in 1907, an argument for the merger of Bradford City with Bradford FC – and with it, relocation to Park Avenue – was based on the fact that Bradford could not support two senior football clubs.

A taste of the future had been provided in 1896 when even the Bradford club was forced to appeal for funds from the public to avert a financial crisis. The commitment to purchase and develop Park Avenue proved onerous and the financial challenge was all the greater because of the competition from Manningham FC for floating spectators in the city. The rivalry of the two clubs was intense, akin to that of a blood feud but the relationship between them is better understood as that of business rivals. The economic reality is that whilst they each had a hardcore of partisan followers they appealed to the wider Bradford public who picked and chose respective fixtures to attend at either Valley Parade or Park Avenue.

The so-called ‘Great Betrayal‘ in 1907 and the abandonment of rugby at Park Avenue defined the future of sport in Bradford. That year brought the formation of a second soccer club – Bradford Park Avenue and the formation of a new northern union side – Bradford Northern. Those who favoured the amateur rugby code decamped to the likes of Bradford Wanderers RUFC (then based at Red Beck Fields, Shipley) or Horton RUFC (at Lidget Green). The sports-loving public was indulged with a choice of options and the different clubs were left to compete for their pennies.

The last hundred years

In the immediate aftermath of World War One, both Bradford City and Bradford Park Avenue were handicapped by the lack of financial resources to sustain success. The death of Harry Briggs in 1920 removed the Park Avenue benefactor and from being rivals in Division One in 1920/21 the two Bradford clubs were both relegated to Division Three (North). It was relatively unheard of, not just that former members of Division One could collapse this way, but that they failed to bounce back immediately. Timing was crucial. The beneficiaries of the demise of City and Avenue were the likes of Bradford RFC, Huddersfield Town and Leeds who stole their custom. Bradford Northern meanwhile continued on a hand-to-mouth existence through the inter-war period, albeit given a fresh momentum by relocating to Odsal in 1934.

Having won promotion back to Division Two, City and Avenue hit a glass ceiling. It left supporters and directors alike frustrated. Attendances were subject to a gradual decline and both became known as selling-clubs. It defined once and for all the relationship between the Bradford public and its soccer clubs, characterised by cynicism and negativity. Crucially Bradford lost the opportunity for one of its clubs to establish itself as a higher division side, similar to the likes of Wolverhampton, Coventry or even Blackburn and Huddersfield. Seen from this perspective, the story of the last thirty years has been about trying to catch-up for those lost decades.

Once again wartime restrictions impacted adversely on the finances of both City and Avenue. The Paraders had been relegated back to Division Three (North) in 1937 and Avenue followed in 1950. In the immediate post-war period they suffered equally from the popularity of speedway at Odsal and the success of Bradford Northern who appeared in three successive Wembley cup finals between 1947-49. By this stage, the Rugby League variant had become the dominant rugby code in Bradford and thereafter, Bradford RFC rarely attracted large crowds to Scholemoor.

As a winter sport, Rugby League was in direct competition with soccer for the same floating supporters. Had Bradford Northern not fallen into decline in the second half of the 1950s – culminating in the liquidation of the club in 1963 – there seems little doubt that soccer would have been delivered a fatal blow. City and Avenue were by this time in a life or death struggle between them as to who would survive. At the beginning of the 1960s it looked as though City would succumb but in the end, after being forced to sell star striker Kevin Hector, it was Avenue who failed to get re-election to the Football League in 1970 and then disappeared altogether in 1974 after a prolonged decline.

Bradford Northern’s own history prior to the appointment of Peter Fox as manager in 1977 was hardly distinguished but the club returned to prominence by winning the Rugby League championship in successive seasons, 1979/80 and 1980/81. Ultimately it was the Super League that revitalised the club and raised public interest after 1995. Across the city, it took a decade and a new generation of soccer supporters to get behind Bradford City who now had the monopoly as the sole surviving Football League side. It was not an easy struggle to overcome the negativity and lack of self-belief of the Bradford public, many of whom had established allegiances with sides based elsewhere. In tragic circumstances, in 1985 Bradford City returned to the second division for the first time in 48 years.

When Bradford City found themselves in the Premier League in 1999, at the same time that the renamed Bradford Bulls were dominating the Super League, it seemed that history had been rewritten. Prior to then, one club – or one code of football – had achieved success only at the expense of another. But of course the glory days didn’t last and both City and the Bulls fell to earth with the hangover of debts to be repaid.

Is it more than a coincidence that the demise of the Bulls in the last five years or so has coincided with the resurgence and reinvention of Bradford City? The main tactic adopted to attract crowds to Valley Parade has been the same as that which had been used previously at Odsal – that is, cheap affordable season tickets and the attraction of a lively, family atmosphere. The Bulls, it seems, have been out-bulled by the Bantams and it represents a particular problem for that club in its current situation given it can hardly afford to heavily discount its prices.

Back in 1905, the leadership at Park Avenue concluded that the Northern Union rugby game could not compete with soccer. It was consistent with what other pundits were saying elsewhere in Yorkshire and Lancashire, leading to radical changes such as outright professionalism and thirteen aside teams to rekindle public interest in the face of the assault from the rival game. Indeed, the introduction of the Super League in 1996 and with it, summer rugby was similarly a response to compete with soccer. In Bradford, for a time it appeared to have succeeded but who would bet on second division Rugby League being an attractive option for the local public as the Bulls face up to a third season outside the upper tier?

Is there now any way back for Bradford Bulls to regain the ascendancy in the city, other than through the collapse of the Bantams at Valley Parade? Leicester, Wigan and Bristol are examples of places where first class rugby has co-existed alongside soccer at a high level. The case of Leicester could be cited as particularly inspirational but what characterises these three examples is that in each case there is the financial backing of a multi-millionaire. A more pertinent comparison is closer to home – in Leeds the Rhinos have undoubtedly succeeded whilst the team from Beeston has been in the doldrums.

Realistically, the only way for both Bradford clubs to simultaneously enjoy success is for them to enjoy the largesse of one or more benefactors. It is generally accepted that for Bradford City to sustain itself in the Championship the increase in wage costs will need to be bankrolled. The same could surely be said of Bradford Bulls.

Sadly the Bradford of today is not one in which millionaires are commonplace. For that matter, even in the decades preceding World War One there was only ever one man – Harry Briggs – willing to invest unconditionally in Bradford sport. The historic attitude was that football had to stand on its own feet.

The record of Bradford football in the twentieth century was insufficient to attract new investors. In fact, it was considered so toxic that it positively dissuaded wealthy men from getting involved by either guaranteeing bank borrowings or underwriting losses. Despite things having changed considerably for the better at Valley Parade it is notable that when ownership of Bradford City was eventually transferred this year, the buyer was ‘not from these parts’. There still seems an aversion among Bradford businessmen to invest.

The ground question

A seeming constant theme in the history of Bradford football has been the ground question and speculation about the relocation of City, Avenue and Northern. At some stage each club has been linked with each of the two other stadia in Bradford although actual periods of relocation have been fleeting. Northern staged occasional high profile games at Valley Parade prior to the opening of Odsal and the Bulls played there in 2001 whilst Odsal was ‘redeveloped’. Avenue spent a solitary, final season at Valley Parade in 1973/74 and of course City played at Odsal between 1985-86 whilst Valley Parade was being rebuilt.

Like a pendulum, the ground question swings back and forth. After the speculation about City moving to Odsal, the difficulties of the Bulls have prompted the suggestion that they will move to Valley Parade. Yet despite the commercial logic of ground-sharing it has never been a permanent arrangement and talk of it is invariably denounced by partisan supporters. Will it continue to be thus if no-one is prepared to underwrite the Bulls? For all the much-vaunted potential and history of Odsal Stadium can the ground really be afforded?

What of the future for Bradford rugby?

Ground-sharing is an obvious financial solution to safeguard senior rugby in Bradford and maintain a tradition that goes back to the 1866/67 season when a Bradford club first played a competitive fixture with representatives of another town (Leeds). Arguably a 150 year tradition is at stake if the rumours of financial difficulty at Odsal Stadium are correct. My own solution is slightly more radical than simply ground-sharing. I would favour the option of creating a ‘Bradford Sporting Club‘, an umbrella organisation embracing not only professional football (rugby and soccer) but amateur sides also.

The original Bradford Cricket, Athletic & Football Club established in 1880 provided the precedent and its success during the 1880s was seen as an expression of Bradford patriotism in what was then an industrial frontier town. It was an organisation that originally existed to promote sport and athleticism in Bradford and forge a civic sporting identity. The modern day variant would similarly promote a single Bradford identity or brand that was shared by every participating sports club in the district. At one extreme this might involve shared financial stakes in Bradford Bulls and Bradford City. At the other extreme a loose confederation of clubs. Arrangements might exist for the professionals to actively encourage amateur sides through coaching support and use of training facilities. It would represent active community involvement. The idea is that every Bradford club – if not, a select group of representative clubs – would then promote a common, shared identity or brand that sat alongside club identities. This would manifest itself with a shared crest or logo on shirts irrespective whether the team competed professionally or in a local Sunday league. If we accept that Bradford’s problem is not one of image, as opposed to identity, sport could be galvanised to promote unity and a degree of social cohesion.

John Dewhirst

John is the author of Room at the Top and Life at the Top which tell the story of the origins of football in Bradford and the rivalry of Manningham FC and Bradford FC. Further details can be found at www.johndewhirst.wordpress.com

Other online articles about Bradford sport by the same author

John contributes to the Bradford City match day programme and his features are also published on his blog Wool City Rivals

=======================================================================

Details about the BANTAMSPAST HISTORY REVISITED BOOKS

=======================================================================