By John Dewhirst

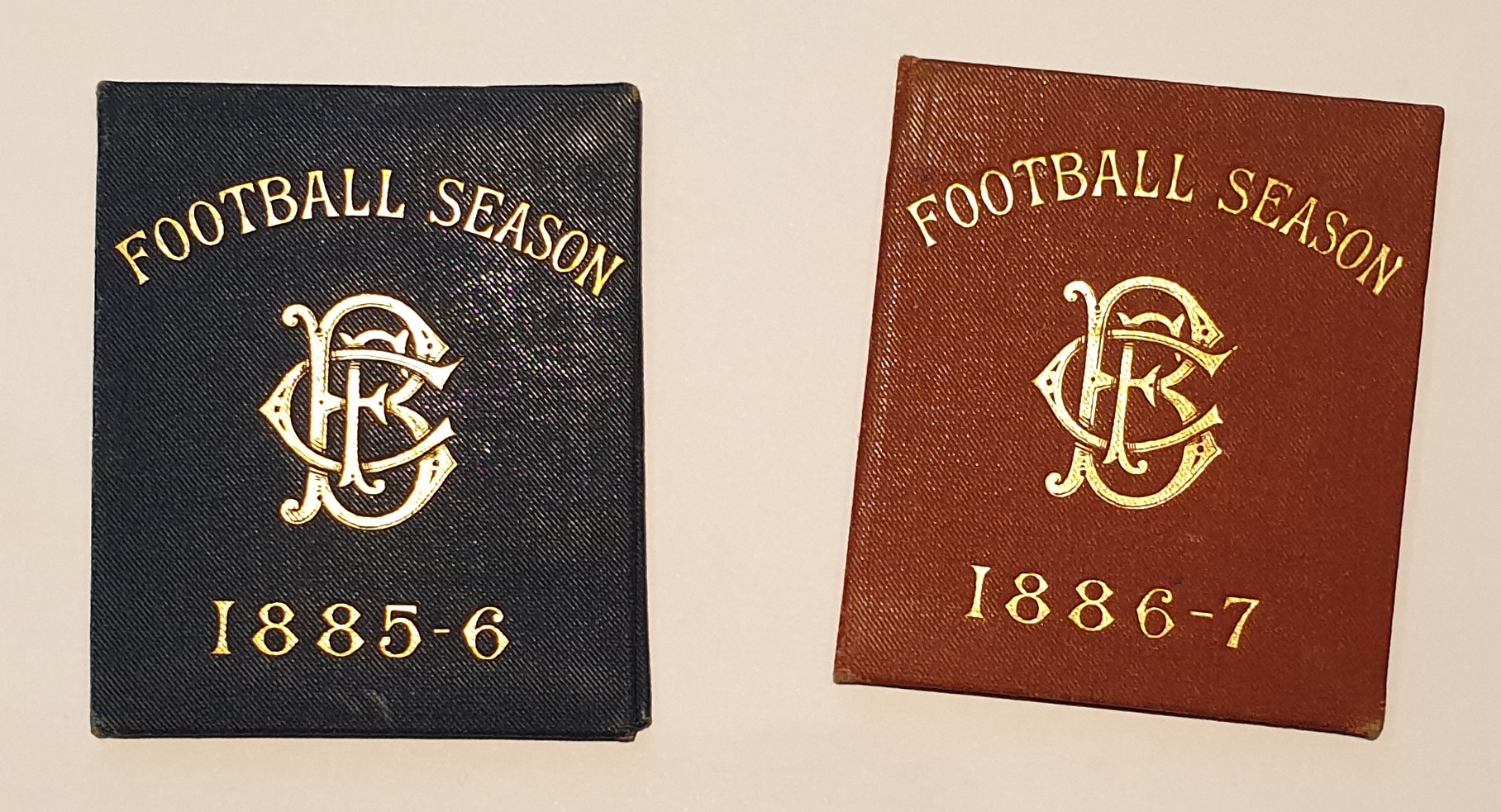

As we approach 2025, locally there’s lots of talk about the celebration of culture. But let’s not forget that there is more to culture than the art-farty stuff fashionable with luvvies. Sport is a big part of culture – a way of life for a lot of people, something that shapes behaviours, embraces passions and forms identities. With regards ‘football’ and its place in local culture, the milestone of when it really began can be traced back 140 years to 1884 when football truly became embedded in local life…

The Victorians regarded rugby and association as two variants of the same sport and made limited distinction between the codes. Indeed, in West Yorkshire rugby was known colloquially as ‘football’ and it was not until after World War One that the round ball game became known as ‘football’. The phenomenon common to rugby football in West Yorkshire and association football in Hallamshire (South Yorkshire), Lancashire and the Midlands was that of becoming a mass spectator attraction and with it, growing commercialisation. With regards association football, the launch of the Football League in 1888 provided a major stimulus whereas in West Yorkshire, it had been the launch of the Yorkshire Challenge Cup in 1877/78 that had promoted public interest.

By the third quarter of the nineteenth century, Bradford was at the height of its textile boom having expanded rapidly as an industrial frontier town. During the 1870s there had been growing demand for recreational opportunities and athletic pursuits, of which rugby football and cross-country / harrier running were the primary outdoor winter activities. During the 1880’s, rugby football came to prominence in the district such that Bradford became known as a hotbed of enthusiasm for the sport. Surprisingly, given the attention given to religion, politics and ethnicity in the social history of the town, the impact of sport in shaping habits and behaviours has been overlooked. This is despite the fact that by the late 1880s the affairs of Bradford’s (rugby) football clubs were a big part of local life, a characteristic now taken for granted in all modern conurbations and thus a key stage in urban cultural development.

(** Links are annoted to other relevant features on VINCIT, refer bottom of page)

A landmark year

If you had to name a landmark year that was significant in charting the course of Bradford football history, it would surely be 1884 when the town celebrated its first major sporting triumph. Thus began an enthusiasm for cup competition that brought the launch of the Bradford Charity Cup and which continued into the twentieth century with the FA Cup and the Rugby League Challenge Cup competition. As events would prove, Bradford clubs were seemingly more adept in knock-out cup competitions and the origins of cup fever in the town can be traced back 140 years when it captured the attention of local people.

This was the year when Bradford FC finally won the Yorkshire Challenge Cup. Not only did rugby become fashionable among all classes of society as a sporting and social phenomenon, but so too the parent organisation of Bradford FC, the Bradford Cricket, Athletics & Football Club became established as a high-profile local institution with its lofty objectives of variously encouraging recreational activity, raising funds for charity and serving as a flag bearer of local patriotism, embodying the pride of a town that had been transformed by the industrial revolution

With regards the origins of (rugby) football clubs in Bradford, they emerged in two distinct waves. The original had been in the late 1870s as enthusiasm for organised football took hold. The second wave came in the aftermath of Bradford FC’s victory with a mania for cup competition. Numerous local sides emerged, inspired by the achievement of Bradford FC and hungry for the glamour of participating in a competitive tournament whether the Yorkshire Cup or the Bradford Charity Cup. It was the success of Bradford FC and its defeat of Manningham FC at Park Avenue in March, 1884 to progress to the quarter-finals, that gave particular impetus to Manningham FC, forerunner of Bradford City AFC which had been formed in 1880. It is no coincidence that Manningham FC came of age in the immediate aftermath of the 1883/84 campaign and progress in the Yorkshire Cup during the two following seasons gave the club’s members confidence to develop Valley Parade as their ground in 1886.

Footballers themselves became local celebrities and feted by Bradford society to the extent that a Bradford-based satirical publication, The Yorkshireman magazine even featured a cartoon about the hangers-on who sought to engage in the social circles of footballers and their partying. Around this time there was the phenomenon of ‘mashers’, the yuppies of their era – young upwardly mobile, nouveau riche males seeking to flaunt their disposable income through the latest clothing and patronage of fashionable restaurants or bars. Support for Bradford FC as well as being seen at Park Avenue and places frequented by the leading players (for example, the Talbot Hotel) was considered a part of this lifestyle.

The partying and the congregation of wealthy people attracted criminals. Capacity crowds at Park Avenue became a magnet for pick-pockets and in March, 1885 for example a number of people were reported to have had personal effects stolen at the Yorkshire Cup game against Hull. However, the partying had evidently become so well-known that, according to the Leeds Times, in December, 1885 a gang of professional thieves from Manchester targeted supporters of Bradford FC in the Talbot Hotel and on Cheapside in Bradford town centre, to steal watches and money. It was clearly worth their while to travel afar.

Winning the cup in 1884 gave a massive fillip to the commercialisation of rugby football in Bradford such that by 1890 Bradford FC was known as the wealthiest club among those playing association or rugby football in England. Likewise, it provided profitable opportunities for others, from provision of refreshments at Park Avenue by Messrs Spink & Co (whose business was given an enormous boost from catering to events staged at the ground by the Bradford Cricket, Athletics & Football Club) to the hoteliers and publicans who served visiting players, club dignitaries and spectators. Not least bookmakers benefited from the interest in football and the predilection for gambling.

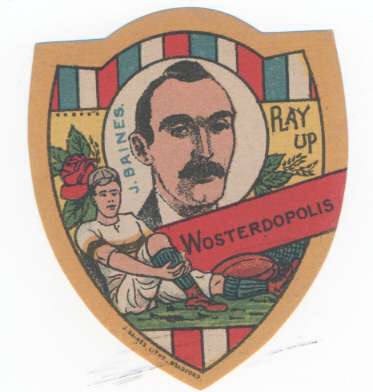

This and other Baines cards featured on this site are from the collection of the author and any reproduction should be credited, preferably avoided.

Locally it also allowed John Baines (1) to build a business through the sale of trading cards that further reinforced the status of footballers as local heroes and celebrities. After 1884 his turnover increased and he enjoyed growing interest in trading cards that allowed him to develop his product, for example with more intricate designs. The origins of the business can be traced to 1882 and initially his focus was the production of cards featuring the names of local football clubs but it is no coincidence that by 1884 his subject matter had shifted to individual players with those of Bradford FC in particular featured extensively. Opportunities also emerged for the supply of sporting goods and trophies (2). Collectively these were formative developments in the evolution of a local football industry.

The significance of 1884 to Bradford’s sporting history therefore cannot be under-estimated. Winning the cup had a major impact on the self-identity of Bradford FC as well as Bradfordians generally, reinforcing a sense of community and civic unity in addition to providing a feelgood factor (3). At a personal level it undoubtedly offered a novel and unprecedented form of escapism and excitement. It also had a transformative effect upon the development of football locally. Such was the popularity of rugby that association football was effectively crowded out, delaying the launch of soccer in Bradford by a generation.

The events of 1884 represented a watershed after which football became firmly embedded in local culture, impacting on public discourse as well as social habits and routines. After that year football was far more visible and prominent, afforded more attention in newspapers than had been the case previously. Hence 1884 can be regarded as a particular milestone locally in the development of traits that we can recognise within modern urban society. What is all the more surprising therefore is why published accounts about the social history of Bradford have thus far overlooked the enthusiasm for football and its impact on life in the town.

A defining purpose

A non-descript retail park on Kirkstall Road, Leeds now occupies the site at Cardigan Fields better known as the location of the first major cup success of any Bradford team. Between 1880 and 1889 (except for 1887) the Cardigan Fields ground hosted the showpiece Yorkshire Rugby Union Challenge Cup Final. The ground – which was the home of the Leeds St John’s club who relocated to Headingley – was subsequently sold for house building and latterly redeveloped to its current use. Yards from where you can nowadays get a Five Guys burger, Victorians came to watch their sport including Bradfordians who witnessed the triumph of Bradford FC in 1884 and the subsequent cup final disappointments of Manningham FC in 1885 and then Bradford FC in 1886.

After the launch of the Yorkshire Challenge Cup competition by the Yorkshire Rugby Football Union in 1877 there had been a local expectation that Bradford FC should satisfy the honour of the town and win the trophy. In the absence of league competition, cup success remained the measure of the best teams in the county and having not been shy of proclaiming itself to be a leading side, the club was expected to prove it.

It was therefore considered anomalous and unacceptable that during the first six seasons of the competition, the town’s premier side had failed to progress. After reaching the semi-final in 1878, the club had been defeated in the early rounds in each of the next four seasons and in 1882 Bradford FC had even suffered the indignity of a giant-killing at Horbury. Getting as far as the quarter-finals in 1883 was insufficient to satisfy expectations. Proud Bradfordians questioned how it was that Wakefield Trinity (three times winners and twice runners-up), Halifax, Dewsbury and even the underdogs Thornes had won the ‘Owd Tin Pot’ and yet Bradford FC – tenants at Park Avenue, considered the foremost sports venue in West Yorkshire and an inspiration for a new ground at Headingley – had failed at the task.

Expectation weighed heavily which is evident from contemporary newspaper reports and accounts of club meetings to the extent that winning the Yorkshire Cup became a defining purpose for Bradford FC and the measure of its existence. In 1882, rugby enthusiasts had thwarted the prospect of association football taking hold in Bradford but there was no guarantee rugby would remain the favoured code in the town if success in the Yorkshire Cup was not forthcoming. (4) There was also the matter of another club claiming Bradford FC’s status as the best team in the town, notably Manningham FC who were then based off Carlisle Road.

The Wakefield bogey

Recruitment of a new generation of players at Park Avenue in 1882 and 1883 had strengthened the Bradford squad and at the start of the 1883/84 season there was muted optimism. Defeat of the club’s old rivals Halifax at Park Avenue in October, 1883 and a successful tour of Scotland in December provided encouragement. The test of the club’s credentials however came at Belle Vue, Wakefield on the last Saturday of 1883 and the long-anticipated fixture against Wakefield Trinity, the cup-holders.

The rivalry between Wakefield and Bradford was intense and Trinity had come to be regarded as something of a bogey side. There was a mutual jealousy: Bradford coveted the cup success of Wakefield whilst the latter could only dream to have the commercial strength of the Park Avenue based club. Bradford’s tour of Scotland had been motivated as much to raise its profile as to emulate Wakefield’s own tour of Ireland.

Defeat at Wakefield was thus a major blow to Bradford FC and its supporters with newspapers quick to highlight that any chance of cup success the following spring was extremely remote. The Park Avenue committee was desperate to rebuild confidence and opted to do so by poaching two of Manningham FC’s best players less than a fortnight later – it was openly reported that the brothers Fred and Frank Richmond had been encouraged to join Bradford FC through financial inducements. On the part of Manningham FC there was anger and the sense that Bradford was actively seeking to undermine their club. The attitude at Park Avenue however was that the town’s leading side needed to be represented by the best players in the town if the Yorkshire Cup was to come to Bradford.

Yet even with the Richmonds in the team Bradford FC was unable to beat Wakefield in the return game at Park Avenue that attracted a then capacity crowd of ten thousand. The report in the Bradford Daily Telegraph of 22nd January was taciturn in its assessment that ‘at the present time at least Bradford has no chance of being able to successfully compete with the Wakefield club for supremacy at football.’

In the cup competition, Bradford at least had the benefit of a favourable draw. In the same way as the World Cup or the Euros, cup opponents were set by a pre-determined format that plotted the permutations of opponents in different rounds. Hence it was possible to work out who a club might play in subsequent rounds and when particular rivals would meet. The only element of chance in the draw was the selection of teams in the first round although it seems likely that there was seeding to avoid the leading sides from meeting until the later rounds.

In the first round Bradford faced Stanley at Park Avenue and in the second round, opponents Wakefield St Austins were offered compensation by Bradford FC to surrender home advantage. Victory for Bradford was something of a formality but what was more remarkable was that the junior Wakefield side exited the competition at the same stage as the senior town club, Wakefield Trinity who fell to a surprise defeat at Heckmondwike. No doubt the upset came as a major relief to those at Park Avenue by eliminating the side that Bradford would otherwise have had to play in the final.

Manningham rivalry

The rivalry between Bradford FC and its successor, Bradford Park Avenue AFC with Manningham FC and in turn, Bradford City AFC came to define Bradford football. It was in 1884 that the two clubs first met.

In the third round, Bradford again had the benefit of a home draw yet whilst the opposition was junior in status, a cup tie with Manningham was anything but the easiest hurdle to overcome. The rivalry had already become imbued with a strong sense of grievance and Manningham supporters considered that the Park Avenue leadership sought to undermine their club. On the part of the town club there was resentment – driven by a sense of entitlement – that the new pretenders aspired to be sporting equals. Denied the chance to play Bradford in the absence of league competition through an invitation fixture, the cup tie offered the opportunity for the Manningham team to prove itself.

What the Bradford club had most reason to fear was the record of Manningham in developing young players and the rise of the latter since formation in 1880 despite the inequality of resources and support. The circumstances mirrored a similar situation at the end of the 1870s when junior clubs had challenged the claim of Bradford FC to be the town’s foremost representative in the Yorkshire Cup competition. At stake was the expectation of Bradfordians to boast that their town was a leading centre of sporting endeavour; for Bradford FC, the commercial and psychological imperative to maintain its status as the leading club and rightful resident of the town’s prestigious sporting venue.

The tie commanded considerable public interest, as reflected by the extent of press coverage. It was no coincidence that the growing enthusiasm for football and cup competition played its own part in the evolution of local papers with dedicated sports journalism. The best example of this was the pioneering Victorian sports journalist, Alfred Pullin (1860-1934), who was known as ‘Old Ebor’ and wrote for the Leeds-based paper, Yorkshire Evening Post. Pullin had strong local connections and he was intimate with happenings in Bradford cricket and rugby such that his commentaries about the affairs at Park Avenue in particular were both extensive and incisive. Pullin’s opinions were highly respected and accordingly he carried influence in Yorkshire rugby as well as being relied upon by betting men for his assessments of form.

By 1884 the affairs of Bradford FC and Manningham FC were also being afforded increasing coverage in The Yorkshireman, a Bradford-based publication that had originally been launched to provide a mix of local social commentary and gossip, political satire and cultural reviews. There was evidently commercial benefit to be derived from diversification into football coverage which extended beyond match reports to the discussion of club affairs and rumour as well as club politics and intrigue. Again, it was both unprecedented and pioneering with its features about the local football scene. (The topic of Bradford sports journalism is a subject for a future feature on VINCIT.)

The preparation of both Bradford clubs for the cup-tie was given extensive coverage including that of Manningham’s training break in Blackpool. The Bradford Daily Telegraph of 17 March, 1884 reported that ‘thirteen of the Manningham players spent from Tuesday morning until Friday evening at Blackpool, where plenty of exercise combined with fresh and invigorating air served to put them in first class condition’.

For most working people a leg of mutton and a fortnight in Blackpool would have been considered a real luxury, not to mention beneficial. Apart from gains to physical well-being there was also a motivational bonus for the players concerned. For the moment we will leave aside the question of how the (amateur) Manningham players could afford the loss of wages or, for that matter how a trip to Blackpool could be afforded by the club, but it demonstrates that there was a willingness to pamper players and a commitment to build team spirit. Never before had a rugby club made such an investment of time and money ahead of a cup-tie. (Ten years later, Manningham FC embarked on another pioneering tour to a fashionable and glamorous destination. On that occasion it was to Paris which was a measure of the club’s upward mobility in the decade.)

In the final event the Bradford team was reported to have been physically stronger and it achieved a convincing victory. The Manningham membership later described this as ‘the famous Blackpool mutton Cup-tie’. In his series of ‘Rugby Memories’ published in the Bradford Telegraph & Argus in 1928, ‘by ‘Bong Tong’ (pen name of journalist Tom Riley) he wrote that whilst the Manningham players were in Blackpool, ‘the Bradford team stayed at home and did little or nothing extra in the way of training. As soon as the game commenced it was plain to see either that the high living at Blackpool had done the Manningham lads no good or that they were not in the same class as Bradford.’

At the finish the ‘mutton eyters’ had been well-beaten. Even so, the Bradford Daily Telegraph of 17 March, 1884 referred to the ‘rising young Manningham club’ and added prophetically that ‘if they were defeated they were not discouraged, and no doubt will again at some future date try conclusions with their powerful rivals.’

The Bradford derby attracted a capacity crowd of between sixteen and seventeen thousand and established new record gate receipts of £280 (the previous record of £262 having been set in January, 1884 for the visit of Wakefield). The Leeds Mercury of 18 March, 1884 described Park Avenue as having been ‘crammed to excess’ with some spectators on the roof of the pavilion to witness the meeting ‘between the premier Bradford team and their small but plucky opponents from Manningham.’ The crowd was reported to have been so large that it encroached onto the field of play and it was also reported that people unable to get access to Park Avenue watched from Horton Park (the Horton Park kop terrace not being constructed until 1907).

However, it was not just the size of the crowd that drew attention in the press but also its composition. Women were afforded free entry to Park Avenue although the expectation was that they were escorted by a male companion. The Bradford Daily Telegraph of 17 March, 1884 reported that ‘the favourable condition of the elements had a further happy effect in tempting numerous ladies to be present on the ground, and enabling them to appear in costumes of more cheerful tones than would otherwise have been the case’.

The Yorkshireman of 22 March, 1884 commented on the ‘amazing popularity attained by the game of football of late years! Who would have been believed ten years ago if he had prognosticated that £260 and £270 would be received as gate money at Saturday afternoon football matches in Bradford?… Roundly speaking, everybody and his wife or daughter were present at the great tussle on Saturday at Park Avenue, and the most fortunate were those who got there soonest… all sorts and conditions of men were represented. There were clergy and ministers, pastors and deacons; very good people and some that were only so-so; lawyers, doctors, magistrates, tinkers and tailors, soldiers and sailors, rag-tag and bob-tail… And better than all, there was a large sprinkling of ladies – bless ‘em, and a good many were evidently partisans, for they wore the colours – black, red and gold – of the winning team, and a striking combination they form.’

The all-Bradford cup tie added a new dimension to the rivalry between the Bradford and Manningham clubs. It was even suggested by those following Bradford FC that Manningham FC should stand aside and not challenge the duty of their club to bring sporting glory to the town. Victory in 1884 defined Bradford FC’s status as the town’s premier representative, a status that was jealously guarded as Manningham FC later rose to prominence. The irony is that victory for Bradford FC in 1884 served only to motivate Manningham FC to emulate the achievement and give claim for recognition as an equal.

The following year Manningham FC would reach the final and had it not been for the fact that Bradford FC was defeated in the other semi-final, the two sides could have contested an all-Bradford final in 1885. In March, 1886 however the two sides met again at Park Avenue for a fourth round quarter-final Yorkshire Cup tie. Again, Bradford FC was victorious although on this occasion it was a much closer match. (That season would be the third in a row that a Bradford side contested the final although it was Halifax that won the trophy.)

Bradford and Manningham were due to play again in March, 1887 in a third round Yorkshire Cup tie that was controversially postponed due to the failure to clear snow from the Park Avenue pitch. Manningham members alleged that the home side had deliberately sought the game to be rearranged to optimise the chance of victory. The dispute eventually led to a legal challenge and a hearing in the Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court which was dismissed. The Leeds Mercury of 19 March, 1887 commented ‘it is regrettable that the Challenge Cup, the possession of which is a much-coveted honour, and the struggle for which brings into play all the dash and bravery of old, should become a bone of strife and bitterness.’

The case received considerable attention in the national press. The Athletic News of 22 March, 1887 reported how the London papers, such as The Globe, Pall Mall Gazette, and St James’s Gazette ‘wax funny at the expense of Bradford’s application for an injunction. The Park Avenue people are unmercifully chaffed, and we are told that ‘since the very first storm that ever occurred in a tea cup there has been no such topic as this.’’ The recourse to litigation came to be seen as symptomatic of the Bradford club’s high and mighty, antagonistic attitude. To suggest that relations between the Bradford and Manningham clubs were fractured by the affair is an understatement.

Thereafter they were kept apart as rugby clubs in the Yorkshire Cup although were drawn together as association clubs in the FA Cup on three occasions with each of the ties played at Park Avenue. Of those games – in February, 1912; December, 1951 and finally in December, 1958 – Bradford City AFC won two and Bradford Park Avenue was the victor in the second. Even in 1912, newspaper coverage referred to the belated revenge enjoyed by the visitors, highlighting the extent to which cup competition remained a central element of the acute rivalry that existed between the two clubs. By the post-war period, the possibility that either of them might be a winner of the FA Cup, (let alone overcome their rival to do so), was remote to say the least but considerable pride remained at stake.

By the end of the 1880s there was a raw edge to the rivalry. After fourth consecutive defeats, Manningham achieved its first victory over Bradford at Valley Parade in September, 1893 in a league match. In its preview of the game the Bradford Daily Telegraph of 30 September, 1893 commented: ‘For a real display of the human passions commend me to a football contest between those very true, sincere, and affectionate friends, the supporters of the two leading Bradford clubs. Both sides regard the meeting today as the new battle of Waterloo. A great question of procedure hangs on the result. In future it will be BRADFORD and Manningham, or MANNINGHAM and Bradford.’

(A few days later came news of the death of a Manningham supporter in the Huddersfield Daily Chronicle of 4 October, 1893, entitled A Football Enthusiast’s Sudden Death: ‘On Tuesday the Bradford coroner held an inquest on the body of Tyas Beaumont (61), a retired coffee roaster of Manningham. The deceased got up on Sunday morning as usual, and was getting ready for breakfast, but shortly afterwards was seen to fall, and he expired almost immediately. He had been talking about the result of the match between Bradford and Manningham just before his death. The jury returned a verdict of ‘Death from natural causes.’ It is stated that the deceased was an enthusiastic supporter of the Manningham club, and that he was very much excited over the previous day’s victory. In talking over the probable result of the meeting to some neighbours during the week, the deceased is credited with having jocularly remarked that if Manningham won he should be content to die.’)

The rivalry appears to have become institutionalised in popular Bradford culture, no less than at the music hall. The Hull Daily Mail of 27 January, 1896 reported: ‘Judging from what occurred at one of the ‘pantos’ in Bradford, the showing of the Manningham colours in the town must produce an effect similar to that produced by exhibiting a red rag to an infuriated bull. ‘Widow Twankey’ in Manningham colours was the signal for a round of hooting which was only stopped when that lady retired. When she re-appeared in Bradford’s colours, a prolonged round of cheering ensued.’

The rivalry between the players was as intense – if not, more – as that between the supporters themselves. The Yorkshireman of 13 December, 1892 referred to the fact that Bradford FC supporters had attended the game between Manningham FC and Dewsbury at Valley Parade after their own fixture at Hunslet had been called-off. It suggested that ‘the old hostility between the two sets of followers was dying out. This was very noticeable again on Saturday, when the Bradford lot shouted lustily for Manningham, and gave them every credit for the good game they had played.’ Notable however was the comment that ‘the players don’t take kindly to each other, as that little scene at night at the Belle Vue Hotel proves.’ Similarly, the Bradford Daily Telegraph of 30 September, 1893 reported that ‘Pocock says if he can only get one more chance at his old enemies and help bring about their downfall then he would not care if the Valley Parade Committee selected him or not. He could then be satisfied with either yes or no.’ (NB Pocock had been Manningham club captain the previous season.) Manningham FC in particular had a reputation for raising their game against Bradford FC, described by the Yorkshire Evening Post in October, 1898 as ‘form which cannot be reckoned on paper.’

Given the emotions, it is not surprising that the atmosphere at derbies was charged and rough play was regularly reported to have been a feature of the games. In October, 1896 it was alleged that Manningham ’s star player George Lorimer had been subjected to physical targeting that had been planned ahead of the game. Writing in the Yorkshire Evening Post of 7 November, 1896 Alfred Pullin referred to comments among Bradford FC supporters in the grandstand enclosure who had encouraged these tactics.

The encounter in February, 1898 had been another violent match in which the Bradford player Jack Crompton was reported to have lost his front teeth. As a result of his conduct in the same game, the Manningham forward, Arthur Leach (who had joined from Bradford FC in October, 1893) was suspended until the end of the season. ‘Old Ebor’ commented in the Yorkshire Evening Post: ‘If I mistake not this is the third time in Bradford v Manningham matches alone in which he has been requested by the referee to retire from play.’ He also reported that ‘‘Until the end of the season’ was also the sentence on six players who made the Bradford-Manningham reserve game degenerate into a Donnybrook Fair.’ It doesn’t require much imagination to work out why the matches became known as ‘skin and hair’ affairs.

These examples serve to demonstrate that the rivalry between the clubs was firmly embedded among the respected players which was at the heart of it. Not surprisingly, this inflamed passions among (non-playing) club members and supporters of both sides. Although there is no record of any trouble between supporters we should not pretend that the late nineteenth century was a mythical era of sportsmanship. The following comment in the Bradford Daily Telegraph hints that derby encounters raised emotions: ‘A parting word to partisans – Whichever team wins kindly brook, no excuses, but win and lose on your merits as true sportsmen.’ The competitiveness of the encounter and the presence of so many people following the other side meant that the atmosphere at Valley Parade or Park Avenue was bound to have been heightened. Indeed, for the same reason, the atmosphere at league games generally must have been distinct from the more traditional match atmosphere for regular friendlies or the visits of touring sides.

In the Yorkshire Evening Post of 18 February, 1899 Alfred Pullin wrote: ‘A year ago I witnessed a game between the two Bradford clubs at Park Avenue. On that occasion the language that was used in the enclosure in front of the members’ pavilion was simply filthy. The worst feature, too, was that those who used it were chiefly lads or young men who have had the ‘benefit’ of modern educational methods.’

Duty and destiny

Back in the 1883/84 Yorkshire Cup campaign, Bradford FC defeated Ossett FC in the fourth round, quarter-final (although had been unable to persuade Ossett to cede home advantage) and then overcame Batley in the semi-final at Halifax to earn a place in the Yorkshire Cup Final against Hull FC.

The route to the Final

1st March, 1884: First Round, vs Stanley (at Park Avenue)

8th March, 1884: Second Round, vs Wakefield St Austins (at Park Avenue)

15th March, 1884: Third Round, vs Manningham (at Park Avenue)

22nd March, 1884: Fourth Round (QF), vs Osset (A)

29th March, 1884: Semi-Final, vs Batley (at Halifax)

5th April, 1884: Final, vs Hull (at Kirkstall, Leeds)

Accounts of the final testify as to the popularity of rugby across all social classes in Bradford. Here was tangible evidence that sport was a social unifier, a goal of those who had been involved with Bradford Cricket Club forty years before and something which had been aspired to when Park Avenue had originally opened in 1880. It strengthened the reputation and profile of the Bradford Cricket Football & Athletic Club as a civic institution in the town and epitomised what might have been described as a ‘One Bradford’ outlook. It also reinforced the self-image of Bradford FC not just as the premier football club in Bradford but as the town’s club, with a patriotic duty to uphold the honour of Bradford.

The same chauvinism – a Bradfordist or Bradford first agenda – that had been a dominant factor in the development of Bradford CC was thus assumed by Bradford FC. Not only would the Park Avenue organisation have been considered fashionable, it would have also been regarded as a respectable and progressive force for social cohesion. It was this which further encouraged the patronage of civic leaders and which inflated the growing self-confidence of Bradford FC, perceived by its critics as high and mighty arrogance. A further outcome was that it led to a mushrooming of new clubs around the town as enthusiasm for football permeated local life.

It was reported that a crowd of fifteen thousand attended the final at the ground of Leeds St. Johns FC and as many as six thousand travelled from Bradford. According to the Yorkshire Post of 7 April, 1884:

‘The match excited a vast amount of interest among the population of Bradford. Swelldom vied equally with the rabble in manifesting their lively concern in the great event of the time. Great numbers, representing the former class, left Bradford shortly after one o’clock in vehicles of all sorts and sizes, including omnibuses and waggonettes, many of the latter being of handsome appearance, drawn by four fine horses, and driven by coachmen in gay livery. Leeds Road was thronged with these vehicles. Vast numbers of other patrons of the humbler sort departed by the excursion trains provided for them by the railway companies. During the afternoon the central streets of Bradford were thronged by persons who were anxious to ascertain the result of the contest, and great was the joy and the commotion manifested in Kirkgate when it was announced that the Bradford team were victorious…In the evening the return ‘home’ of the victorious team was commemorated by a popular demonstration regarded as quite unique in its intensity. The team arrived late at the Midland Station but in the meantime the band played a variety of popular airs, including frequently ‘See the Conquering Hero Comes’.’

Those who could not attend the game relied on telegram updates of the score with news spread among crowds waiting in central Bradford and those congregating outside the Talbot Hotel on Bank Street. Newspaper reports refer to supporters of the club wearing ribbons in its colours of red, amber and black – an illustration of how traders capitalised on the occasion.

The team was conveyed to the Talbot Hotel and the victors ‘were everywhere hailed with immense cheering.’ An immense crowd filled Kirkgate whilst the team were entertained to dinner at the Talbot Hotel. The celebrations were unprecedented, the achievement being as significant in its day as the FA Cup victory of 1911. Not everyone however was happy about the festivities as the following letter from ‘An Indignant Father’ printed in the Bradford Daily Telegraph of 9th April, 1884 attests:

‘I see the papers to-day have a great deal to say about the great victory the Bradford football team won on Saturday. I can understand this and feel proud too of the skill and courage which led up to the result. If there were nothing also I would heartily join in the general chorus of congratulation. But I am grieved to learn that there is another side to the victory, one which makes me ask whether the prize, valuable as it is, may not have cost more than it is worth. I have heard from the father of one of those who took part in Saturday’s proceedings a story that causes me to feel ashamed of my young townsmen. He tells me that the dinner degenerated into a drinking bout, and that many of those at it were in a state of dreadful intoxication, many of them not reaching home till next day, and then in a condition which I will not attempt to describe. If these are to be the consequences of winning the cup I am sure I heartily hope that it may be long before there is another occasion for such proceedings. I am sure that if the Football Club desire to enjoy public sympathy and support they will exert themselves to avoid anything that has a tendency to encourage among their members drinking as to lessen the disgrace attaching to being drunk.’

The celebration of cup success in 1884 defined the practice in Bradford for future occasions, combining the reception of the winning team by a brass band and involving a processional march. Indeed, this was later replicated by Manningham FC in 1894 to celebrate winning the Yorkshire Senior Competition and again repeated with a parade through Manningham on 25 April, 1896 to celebrate the club’s Northern Rugby Football Union championship. The same format was even the basis of the funeral procession for Manningham FC player, George Lorimer in February, 1897.

The Bradford Daily Telegraph of 8 April, 1884 reported that ‘the goal of the Bradford Club’s ambition has been reached at last.’ The triumph distracted from the fact that the club had been defeated twice by Wakefield in the 1883/84 season. Instead, cup victory had a profound impact on Bradford FC and encouraged a sense of invincibility. For a start, defeat of Manningham FC had left no-one in any doubt – for the moment at least – about the club’s premier status in the town and by winning the Yorkshire Cup it could claim primacy in the county.

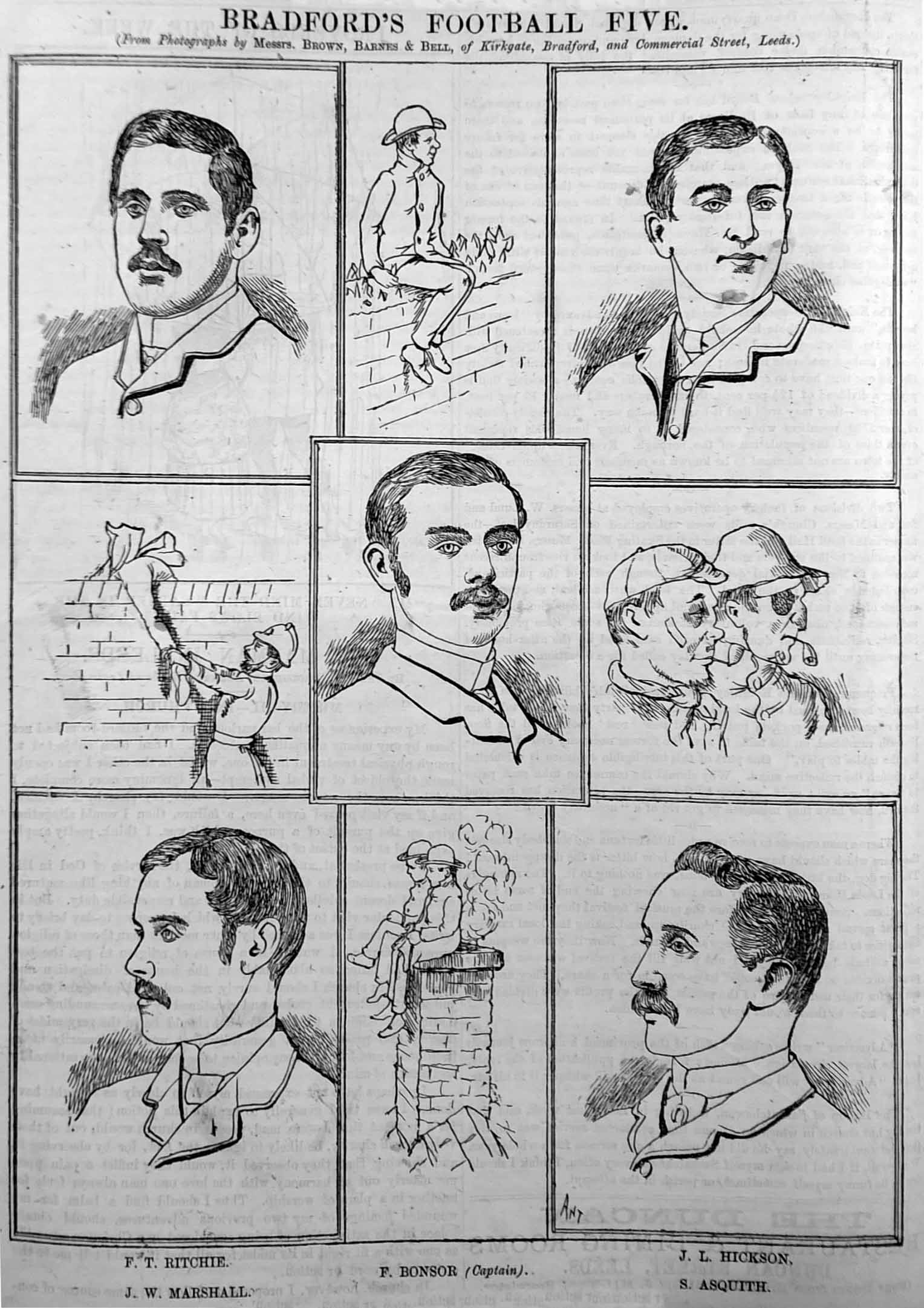

The winning team – Fred Richmond, Robert Robertshaw, Edgar Critchley, Frank Ritchie, Fred Bonsor (captain), James Wright, Laurie Hickson, Sam Asquith, Edgar Wilkinson, Proctor Carter, Herbert Robertshaw, John Marshall, Sam Haigh, Tom Atkinson and Joseph Potter – became feted as Bradford celebrities. The players were all local men and of mixed social composition: Carter, the spinning overlooker; Marshall, the warehouseman; Richmond, the gardener; and the Robertshaws, Bonsor and Hickson who were the privileged sons of successful woolmen.

The hubris

The profile of Bradford FC was enhanced enormously. Such was the new-found prestige of the club that it was able to arrange a tour in November, 1884 to play Marlborough Nomads (at Blackheath), Oxford University and Cambridge University. The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News of 29 November, 1884 reported that ‘the tour of the Bradford Club has excited far more interest than any matches that have been played under Association rules.’ The Bradfordians returned home undefeated with wins against Marlborough and Cambridge and a draw in Oxford.

In December, 1884 Bradford FC defeated Llanelly FC, holders of the Welsh Cup at Park Avenue. Although the visitors included three guest players from Hull, the Bradford side was under strength and the result was interpreted as further affirmation of the club’s strength. Sporting success reinforced the self-belief – and what might even be described as a sense of entitlement – that already existed in Bradford (in abundance) and the achievement of the club was emulated in succeeding months by Bradford Harriers (cross country running) and Bradford Chess Club. (Chess was a popular activity in Bradford at the time and widely reported in the press, the equivalent of ‘mental athletics’.) As significant, in the final game of the year there was also victory over Wakefield Trinity at Park Avenue – this time in front of a reported seventeen thousand, the ground having been expanded to cater for growing crowds – with a last-minute try scored by Joseph Hawcridge, another player poached from Manningham FC.

(In its own attempt to save face, the Wakefield club disputed the result but was unsuccessful in appealing to the RFU for it to be reversed. The return fixture at Wakefield however never took place and was postponed twice on account of Bradford FC claiming that it was unable to raise a side. The episode added to the mythology of the rivalry and Trinity supporters inevitably claimed that the Bradford captain, Fred Bonsor was afraid of bringing his team to Belle Vue.)

The cup success of 1884 became part of Bradford folklore with routine mention in the Bradford press for the next five decades as it remained in living memory. Members of the winning team also accrued considerable influence in club politics at Park Avenue. The achievement of having won the cup – and the subsequent glory era enjoyed by Bradford FC before the formation of the breakaway Northern Union in 1895 – inevitably encouraged a nostalgia amongst Bradford supporters about former membership of the English Rugby Football Union. In turn this led to the launch of Bradford RFC in 1919 and revival of Rugby Union in the city.

Winning the trophy played a big part in helping to define – in addition to reinforcing – the self-identity of Bradfordians. With regards civic pride, Bradfordians could hardly complain at a Leeds newspaper offering praise: ‘Bradford has the distinguished honour of holding three silver challenge cups. Her stalwart football team were winners of the Yorkshire Football Challenge Cup; her fleet ‘Harriers’ ran away with another cup from Leeds; and, to crown all, her astute chess players carried off the West Riding Association Challenge Cup. These three honours are but an exemplification of the pluck and enterprise of Bradford men. Whatever they attempt they do with all their might; throw their whole soul into the task; ‘never say fail’ is their motto; and this principle, which applied equally to the public affairs of the borough as to its individual citizens, accounts, in a great measure, for the rapid progress and prosperity of the borough.’ (The Leeds Times, 7 February, 1885).

Bradford prided itself that ‘Labor Omnia Vincit’ was not an idle motto and that it was a guiding principle and spirit of the town. The observation in The Leeds Times reveals how sport could provide an affirmation of the Bradford psyche and how sporting success was seen as the prize of a work hard, play hard outlook. This was not confined to the field and in September, 1886 for example The Yorkshireman referred to the fact that ‘complaints have frequently been made by our neighbouring football friends of the extreme partisanship of the Park Avenue spectators.’ This demand for success played its part in shaping the culture of the club. In 1884, as in 1911 when Bradford City AFC won the FA Cup, it was a feature of the Leeds press to question when Leeds might emulate Bradford’s sporting glories and there is an element of self-doubt on the part of the (Leeds) journalist who wrote what he did in 1885. A compliment indeed about Bradford sport and the will to win.

As to why Bradford should have established sporting ascendancy over Leeds, my observation is that in Leeds there was greater fragmentation of sporting effort and in the nineteenth century at least, Leeds Cricket, Football & Athletic Club at Headingley was late in asserting itself as the local champion. Equally it could be suggested that with regards association football, Bradford did not sustain success at a national level in the twentieth century due to the fact that neither Bradford City nor Bradford Park Avenue enjoyed the civic monopoly of Leeds United and hence Bradford lost the advantage.

In the aftermath of cup victory Bradford FC was successful in developing a national profile and reputation as one of the leading sides in the country and the ability to command prestigious fixtures. There was even the suggestion of playing exhibition games in Germany in 1886 but despite the promise of expenses being underwritten, the tour never materialised. In practice the Bradford leadership was calculating when arranging its tours with regards to optimising the club’s reputation. By the end of the 1880s the club’s annual tours had become infamous, said to be done in regal style with questions of cost a mere detail which, according to Alfred Pullin in The Athletic News of 18 November, 1889 was characteristic of Bradford FC. Not least the club also established an enviable record of Park Avenue players being ever-present in the England Rugby Union team between 1885-95 (5) and by offering a higher probability of selection for Yorkshire and England, it ensured that the best players were attracted to play for Bradford FC.

By the second half of the 1880s the club was being accused by its Yorkshire-based rivals of its arrogant outlook and whilst jealousy was a factor in this, there was also substance to the accusation of the self-assured hubris of the club’s leadership. This personality was virtually a caricature of the brash, self-made and nouveau-riche men who had made their wealth from Bradford’s wool trade, for whom the success of Bradford FC would have appealed to their vanity by giving further recognition to the town in which they had flourished. The club proved adept at self-promotion and getting national attention as a sporting phenomenon of the age such that Bradford FC – and Bradford rugby – would enjoy peak fame during the next decade. By contrast, Wakefield Trinity – winners of the Yorkshire Cup three times and runners-up twice in the first six seasons – never attained the same profile or became as fashionable.

Football mania had no bounds as this classified advert from January, 1885 demonstrates, another example of how traders looked to capitalise on interest in football. The fact that the cup victory should be commemorated on a piano might seem bizarre but it reveals the pride and cachet of the achievement for this to have been a design feature of a premium consumer product.

Charitable purpose

It was a characteristic of Bradford FC that it sought to differentiate itself from its rivals by claiming that it served a higher purpose and there were two elements to this, the first of which was the promotion of recreational activity as an antidote to hard work. This sentiment had roots in the politics of the 1840s when the Tory sponsors of Bradford Cricket Club had seen the opportunity to attract working class support and challenge the Liberal, non-conformist mill owner establishment but it evolved to demonstrate that Bradford and its people had interests and passions beyond work. The second dimension was the promotion of charity fundraising, establishing a tradition of support from Bradford sportsmen for the town’s infirmary which continued through the inter-war period (for instance with gate receipts from pre-season friendlies at Valley Parade or Park Avenue donated to charity).

In order to demonstrate the club’s commitment to charity fundraising, immediately after the Yorkshire Cup Final the Bradford FC leadership gave its encouragement to a game at Cardigan Fields on 15 April, 1884 – a mere ten days after the earlier cup victory at the same venue – at which a Leeds & District XV played a Bradford & District side to raise money for the Leeds and Bradford Infirmaries. The following month, the Bradford Charity Cup competition was instigated by Bradford FC with the patronage of the Mayor, Isaac Smith as the club continued to bask in the glory of its cup success. (6)

The launch of the new local competition – for what became known as the ‘small pot’ as distinct to the ‘T’owd tin pot’ by which the Yorkshire Cup was known – fuelled cup fever and this contributed to an explosion in the formation of new clubs in the Bradford district (7). In turn Bradford became a rugby stronghold. Association football was quite literally crowded out with nowhere to stage soccer and no-one to play the alternative code which had implications for the development of professional sport in the district.

By 1890 Bradford FC was recognised as the wealthiest football club in England. With the accumulation of profits, Park Avenue was progressively upgraded to accommodate ever-larger crowds. However, anxious to avoid the suggestion that it was chasing mammon the club steadfastly proclaimed its commitment to charitable fund raising. The club’s mission became that of securing ownership of Park Avenue to provide a dedicated venue for sporting activity in the district and in turn, a means of supporting local charities.

The club’s commitment to rugby would eventually prove a disadvantage and the launch of the Football League in 1888 ensured that in terms of balance sheet strength, Bradford FC would soon be overtaken. Ambitions to develop a three-sided ground at Park Avenue were revealed in 1893 but later abandoned as the club struggled to repay borrowings taken out to secure the long leasehold of the ground. Inevitably the commitment to charity fund raising became sacrificed to financial survival.

The match day experience

Although high profile cricket fixtures staged by Bradford Cricket Club had attracted large crowds (probably no more than five thousand), the only precedent for mass spectator events in Bradford had been the Whitsun Galas at Peel Park that reputedly attracted crowds of sixty thousand. The attendances at Park Avenue did not exceed the numbers reported to have attended the latter, but what was unique about them was the frequency and regularity of large crowds. With regards the match day experience the biggest differentiator with today would have been the lack of attention to health and safety considerations.

For a start, ground facilities were rudimentary with terracing invariably being no more than earth mounds topped with chimney waste, for example ashes or clinker. Even the prestigious pavilion at Park Avenue with little more than a basic grandstand with basic, bench seating. High profile matches increasingly attracted bumper crowds that forced pressure for the progressive expansion of Park Avenue.

Understanding of capacity limits was crude and subject to arbitrary estimates. Entry of people to the ground would have been based on what was physically possible as opposed to defined limits. The comfort and convenience of spectators was a secondary consideration, a charge equally applicable to leading British football clubs until the 1980s.

On Christmas Day, 1888 a twelve year old boy, Thomas Coyle was killed only seven minutes into a game at Valley Parade as a result of the collapse of the wooden pitch perimeter barrier on the Midland Road side. He had been a member of a reported ten thousand crowd for the visit of Heckmondwike and this must have been the upper tolerance of what the ground could accommodate – much less than the much vaunted eighteen thousand capacity.

The wooden barriers were ill-suited to withstand a crush and the inquest was told that the foundations on the ash banking had yet to settle, a problem no doubt exacerbated by the soft ground conditions caused by rain. However, the inquest was told that there had been a similar incident the season before. Comment was also made at the hearing that the barriers were not as strong as those at Park Avenue. The fact that a reported crowd of twenty thousand had attended the Boxing Day derby between Bradford and Halifax – and that a similar incident had been avoided – would not have been unnoticed either.

The adequacy of facilities at Park Avenue to safely accommodate large crowds was questionable although thankfully there was no loss of life as at Valley Parade in December, 1888. An account in The Yorkshireman of December, 1884 testified to the cramped conditions with people tightly packed at the time of the Wakefield game. Warnings of a potential incident were highlighted by a report in the Bradford Observer of 22 September, 1885: ‘The increased accommodation in the pavilion and enclosures is a great boon to the members…The alterations are not quite completed, and it might be suggested to the management here that the enclosure stand is far too close to the railings at present and will result in the latter giving way under pressure, with possible danger to life and limb. There ought to be fully twice as much space as there is at present between the last row on the stand and the railings.’

A crowd of twenty thousand attended the game with Halifax on 4 March, 1893 (the decider of the Yorkshire Senior Competition) which highlighted the capacity constraints of the ground and the urgency for redevelopment. What is remarkable is that the bumper gate with its record receipts came on the same day that twenty-two thousand attended the England international against Scotland at Headingley in which Toothill and Duckett of Bradford FC represented the home nation. The Halifax derbies were popular and two years before, a crowd of just under twenty thousand had attended a cup-tie between the teams at Park Avenue. There had been a similar attendance on Boxing Day, 1888 for the same fixture and at the time, both of these games represented then record gate takings.

The Bradford Daily Telegraph of 7 March, 1893 reported that: ‘As the enclosures and stands became packed the boundary walls soon began to swarm with persons. Considerable amusement was caused by the swarm of youngsters who were pitched over into the field, to make room for the late arrivals. The safety of spectators was a secondary concern and the game was delayed following the collapse of a barrier at the town end of the field owing to the surging pressure of the crowd.’ Thankfully no-one was reported to have been injured.

An account of the same game was provided in the reminiscences of former Bradford FC President, Mr TA Corry in January, 1915: ‘Just before half-time one set of railings gave way, and a couple of thousand spectators rolled down the bank on to the field. Fortunately, only one boy complained of his leg being hurt. The situation looked very dangerous as the crowd got close up to the goalposts. At half time there was discussion about abandoning the game but the Halifax captain preferred to go on. I spent the rest of the game on the field trying to keep the crowd in order.’

Another near escape was reported by the Bradford Daily Telegraph on 20 September, 1897: ‘During the progress of the Bradford v Heckmondwike match at Park Avenue on Saturday, the football pavilion caught fire at the Horton Park end. The blaze, however, was extinguished with a couple buckets of water.’

The Bradford Daily Argus of 6 March, 1897 similarly included an account of straw being set ablaze on ‘the touchline of the 3d side’ (that is the Horton Park Avenue side) that caused the game to be stopped for a few minutes whilst a policeman smothered the fire with more wet straw. It was said that the fire was attributed to a spectator who had been swearing because Bradford had missed a chance to score and presumably, in his rage he had dropped his pipe.

Describing the record attendance at Park Avenue, the Yorkshire Post of 6 April, 1904 stated ‘the number of people admitted to the ground – reported to be 27,000 – was really larger than was consistent with safety’ and reported how barriers at the city end of the ground had given way: ‘those in the front were hurled forward, and those directly behind fell on top of them. Just for a moment it appeared as if a serious accident had occurred, and it was a great relief to find that those in the melee were more frightened than hurt.’ It added that ‘from the time the barriers gave way until the close of a most stubborn and exciting game the self-restraint of the encroaching crowd was simply splendid. Hundreds of persons could not help being forced inside the enclosure, but once there they did all that men could do to avoid interference with the game and see that the combatants had fair play. It was as fine an example of the real Yorkshire Sportsmanship as one could possibly wish to see.’

Police attendance at games was not for the purpose of crowd control or safety management as opposed to deterring theft or robbery. Packed crowds encouraged pick-pockets although this was by no means a new issue and the minutes of a Bradford Town Council meeting in September, 1848 reported police attendance at cricket matches staged by Bradford CC at its former Claremont ground to provide deterrence. Disclosure of the cost of police wages in the accounts of Bradford FC would similarly suggest between five and ten policemen on duty at Park Avenue on matchdays in the 1880s to deter pickpockets and prevent the theft of gate receipts.

Bradford FC and Manningham FC were the largest clubs in the Bradford district but were not the only ones established on a commercial basis. What came to characterise Bradford football was the number of gate-taking clubs with as many as thirteen gate-taking sides within the current Bradford Metropolitan District, a statistic that is significant in itself. The principal clubs were as follows: Bradford; Manningham; Bowling (8); Bowling Old Lane; Shipley (7); Saltaire; Windhill; Idle; Wibsey; Bingley (9); Keighley; Ingrow; and Silsden. However there were other village sides in addition to these who committed to renting fields and whose operating expenditure was also dependent upon spectator monies – for example the likes of Buttershaw, Heaton, Wibsey and Wyke who were enthusiastic competitors in local charity cup competition. Aside from a limited number of cup-ties, median attendances at these clubs would have been a fraction of those at Park Avenue, Carlisle Road or Valley Parade (after 1886) and in practice the vast majority of those clubs struggled to remain solvent. Nevertheless it demonstrates the extent to which football had captured the local imagination and of how the business of football became established. It was evidence of the phenomenon of how a sport had become monetarised and then commercialised to create a widespread business activity.

Although there are reports of players or referees being routinely abused, I have not come across any mention of crowd violence. When trouble did arise, this was typically attributed to gambling disputes as opposed to partisan loyalty.

As referenced in this account there are numerous reports in contemporary newspapers to foul language at matches. There is however no mention of communal singing which, in Bradford at least, was a phenomenon that did not emerge until after rugby was abandoned at Valley Parade in 1903 with terrace songs that could be traced to a combination of music halls and viral spread from hearing the songs of supporters from other clubs.

Partisan rivalries

New rivalries emerged between junior sides across the district but none could match the sheer intensity and pettiness of that between Manningham FC and Bradford FC which continued in the twentieth century through the rivalry between Bradford City and Bradford Park Avenue. However, it is wrong to claim that the basis of the rivalry was based in social class, religion or ethnic division (10). Underlying the rivalry was urban geography. The fact that Park Avenue was relatively inconvenient to access from Manningham and the corridor in north west Bradford where much of the urban growth was focused gave impetus to a club becoming established on the other side of town. Ultimately the distinction between the clubs had more to do with the grounds that they were based at – Park Avenue being a cathedral of sport as opposed to the more utilitarian Valley Parade being better described as a chapel.

In time it became appropriate to describe the rivalry of the two clubs as derived from a narcissism of small differences. However, what animated their supporters were the myths, legends, accumulated grievances (imagined and real), heroes and personalities which added to the innate competitiveness that came bundled up with following Bradford FC or Manningham FC. It would be wrong to say that football culture began in 1884, but what happened in that year provided the ingredients to bring substance. From thereon, football began to matter.

The cup success of Bradford FC in 1884 served to motivate Manningham FC who reached the final of the Yorkshire Cup in April, 1885 and were defeated by Batley who had beaten Bradford FC in the semi-finals. An all-Bradford cup final in 1885 would have been a momentous event and crowned the growing reputation of the town as a centre of sporting activity.

(Notable is that in 1885 a change of diet was instituted for Manningham players as reported by The Yorkshireman of 28 March, 1885: ‘Last year at this time, when training for the Cup, after his sprinting he could sit down to a good feed, consisting of oysters, beefsteaks, mutton, etc; but now, alas, he has to be content with a teacake and a pint of tea…‘ A week later, with the club having defeated Dewsbury to gain a place in Yorkshire Cup Final, The Yorkshireman commented that ‘A certain stalwart Manningham forward was strolling along the Lane on Saturday night when he met a prominent Bradford player, who congratulated him heartily on Manningham’s victory. ‘’Yes, yes,’’ replied the Manninghamite, with a wry smile, ‘’muffins and teacakes have not been so bad for training purposes, after all!‘’ ‘ Consistent with the more puritanical approach, another training camp was arranged ahead of the final with Batley but on that occasion, it was to Morecambe where there were fewer distractions compared to Blackpool. In February, 1906 the practice was revived by Bradford City AFC which had a fortnight’s training break in Blackpool in advance of the Third Round FA Cup tie at Everton.)

The Manningham-Bradford rivalry became even more bitter in 1887. The relationship between the two clubs dictated the future of professional sport in Bradford and their conversion to soccer in the first decade of the twentieth century. The reluctance to join forces through amalgamation and the fragmentation of sporting effort was surely at the expense of future glories. Thus the events of the 1880s helped shape the future of football in the district and in turn, Bradford football became the prisoner of its history.

The historic context

Sadly, future occasions for sporting celebration in Bradford were few and far between which might explain why the achievement of 1884 remained uppermost in the sporting folklore of the town in the late Victorian era. For example, in 1885 Manningham FC was defeated in the final of the Yorkshire Cup and then in 1886, Bradford FC lost to Halifax at Cardigan Fields. Enthusiasm for the competition became much diminished at Park Avenue in favour of high-profile invitation fixtures and Bradford FC did not enter in either the1887/88 or 1888/89 seasons. Between then and 1895 both Bradford FC and Manningham FC reached the semi-finals on two occasions (Bradford FC in 1890 and 1894; Manningham FC in 1893 and 1895) but the cup did not return.

It seems incredible that even in the late nineteenth century heyday of Bradford rugby, headline trophy success was rare. The next occasion that a Bradford rugby union club won the Yorkshire Challenge Cup for example was in 1923, long after the rugby schism of 1895 and when the trophy was much diminished in stature (11 & 12). Manningham’s success as inaugural champions of the Northern Union in 1896 was the next major success for a Bradford side followed by Bradford FC winning the Northern Union play-off in 1904, the Challenge Cup in 1906 and the Northern Union Yorkshire Cup in 1907.

The intense rugby rivalry of Bradford FC and Manningham FC continued after the respective cubs converted to association football at Valley Parade in 1903 and at Park Avenue in 1907. Whilst at the latter, Chairman Harry Briggs dominated decision-making, to all intents and purposes the two organisations operated much the same as association clubs as they had as rugby clubs. Indeed, although they attracted new, predominantly younger followers there remained considerable institutional loyalty to the respective ‘new’ clubs from existing supporters. For example, at Park Avenue this overcame much of the bitterness about abandoning rugby and at Valley Parade in particular, there remained a strong Manningham identity despite the change of code. The football experience in Bradford thus continued to be overshadowed by the petty jealousies of the two long after rugby was abandoned to the extent that it was almost incidental what shaped ball was being chased on the pitch. Indeed, it was far from the case that conversion to association football represented an entirely clean break from the past and a reset of local football culture.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, association football was in the ascendancy in Bradford and interest in rugby was waning. The achievement of Bradford City AFC winning the Division Two championship in 1908 and then the FA Cup in 1911 overshadowed the earlier triumphs and ‘Glorious 1884’ was thus forgotten.

In many ways the triumph of 1911 mirrored that of 1884 in so far as the population of Bradford had an expectation of sporting glory to complement the commercial, cultural and civic accomplishments of a confident and successful metropolis. As in 1884, sporting glory in 1911 played a big part in consolidating local pride and a sense of local patriotism in Bradford. Likewise, just as the 1884 victory became a big part in the self-identity of Bradford FC, so too ‘Glorious 1911’ did much the same for Bradford City AFC. As with Bradford FC at Park Avenue after it became a founder member of the Northern Union in 1895, memory of cup glory sustained a sense of self-belief and pride at Valley Parade long after that club’s glory era had disappeared.

Neither Bradford City not Bradford Park Avenue were particularly successful in league competition and between 1908 and 1970 when the city of Bradford had two representatives in the Football League, they managed only three promotions apiece. Had rugby been abandoned much sooner, it is possible that Bradford could have established itself as a soccer hotbed (13). It remained cup competition that focused the interest of the Bradford public with celebrated (if not rare) exploits in the FA Cup during the post-war period. Successive generations all hankered for the chance of cup glory such was the local sporting folklore that had surrounded the success in 1884 and later in 1911.

As to why the two Bradford clubs proved more adept at preparing for cup games than sustaining effort over the course of a league season may be explained by their status in the football world. Their fall from grace after World War One was accompanied by financial difficulty and lack of strength in depth. On the one hand it meant that they had limited resources to build a squad of players to be consistently successful but on the on the hand, there was a financial imperative to achieve success in the cup simply to generate revenue.

After the disappearance of Bradford Park Avenue, the achievement of Bradford City as a basement club reaching the final of the Football league Cup at Wembley in 2013 and the famous victory in the FA Cup at champions, Chelsea in 2015 maintained the record of cup exploits.

Bradford Northern RLFC (the successors to Bradford FC in the Northern Union / Rugby League) and Bradford Bulls (as Bradford Northern became known after 1996) likewise derived their own reputations from cup competition – for instance with three successive Wembley Challenge Cup finals between 1947 and 1949 including victory in 1944, 1947 and 1949 and latterly three World Club Championship successes between 2002 and 2006. (14)

Read more in ROOM AT THE TOP and LIFE AT THE TOP by the same author, published as apart of the BANTAMSPAST HISTORY REVISITED series

Notes and links to relevant features published on VINCIT about the early history of football (rugby / soccer) in Bradford:

- Collectors guide for Baines trading cards (NB John Dewhirst is collaborating in the production of an in-depth history of Baines cards with likely publication in 2026)

- The story of Tony Fattorini, the original sports marketeer

- The significance of sport in shaping a Bradford identity

- The late development of soccer in Bradford

- The England RU internationals of Bradford FC

- The History of the Bradford Charity Cup

- The story of Shipley FC and Bradford’s other long forgotten nineteenth century junior rugby clubs

- Usher Street, the story of a Victorian urban sports venue

- The History of Bingley FC

- The myth that the City-Avenue rivalry was based on class politics

- The revival of Bradford Rugby Union in 1919

- Bradford RFC in the 1920s

- What if rugby had been abandoned in favour of soccer in Bradford much sooner?

- Bradford’s rugby heritage

The author’s blog can be accessed from this link which has other features about the history of Bradford sport.

Thanks for visiting VINCIT, the online journal of Bradford sport history which features all clubs and codes of sport in the district. The motivation for the site was to ensure a resource for people interested in the origins and history of Bradford sport without recourse to superficial, inaccurate and on occasions, imagined narratives that are commonplace on the internet and social media. The same objective is behind the BANTAMSPAST History Revisited series of books about the history of Bradford football.