Bradford City AFC is best known for its exploits in cup competition in 1911 and as recently as the past few seasons. To a lesser extent, Bradford Northern likewise for its record in the Rugby League Challenge Cup during the 1940s. So too, Manningham FC – predecessors of Bradford City at Valley Parade – was a club whose origins and early development had much to do with participation in cup campaigns. Rightly so, the Yorkshire Challenge Cup launched in 1876 and first contested in the 1877/78 season is credited for its impact on the spread of ‘football’ in the Bradford district and the stimulus that it provided to a footballing culture in the town.

Another competition, the Bradford Charity Cup instituted at the start of the 1884/85 season, deserves to be recognised for having fuelled local interest in football despite the fact that – in its original incarnation – it had a relatively short life of only ten seasons. Its link to charitable support also embraced a key tenet of athleticism in Bradford, the conviction that financial surpluses from organised events should be donated to help fund the town’s infirmary rather than the pursuit of Mammon.

The Bradford Charity Cup has a unique place in the history of Bradford sport, a trophy that was adopted by three different football codes in the space of thirty years. It similarly provided inspiration for the Priestley Cup of the Bradford Cricket League, launched in 1904 and still in existence today. Despite its impact on the development of Bradford sport, the Bradford Charity Cup has been forgotten.

Charitable motives were critical in the development of Bradford sport and you cannot tell the history of sport in the district without recognising the importance of charity fundraising intentions. This is the story of what was called the ‘small pot’.

The ‘Owd Tin Pot’

The Yorkshire Challenge Cup – the ‘Owd Tin Pot’ – immediately captivated the minds of football enthusiasts in Bradford. The competition had been promoted by Harry Garnett of Bradford FC. On the basis that the club considered itself to be one of the leading sides in the county, there was an implicit assumption that it should be victorious which meant that defeat at the hands of eventual winners Halifax FC in the semi-final tie at Apperley Bridge in December, 1877 was notable for two reasons. Apart from shattering the complacency that Bradford had a divine right to success, it also challenged the existing order in so far as Halifax had been a completely unfancied side. The dream was thus born that cup glory was in the reach of a well-organised team and that the pedigree of a club was no guarantee of winning.

During the second half of the 1870s there was a dramatic change in the life of working men in Bradford who were now able to enjoy greater recreational time. It is no coincidence that growing enthusiasm for football – the colloquial term for rugby – came after the passing of the Factory Act of 1874 which had led to the closure of mills at noon on a Saturday.Having secured leisure time, people wanted to make the most of it and what is striking from contemporary newspaper reports is the sheer passion for ‘football’ that was shared by those who played the game. It was not just an opportunity for an idle kick-around as opposed to a pastime played with intent and for a purpose. Indeed, there was considerable competitiveness among players despite the fact that for most, their induction was recent. This soon translated into a focus on winning the Yorkshire Cup which was at the centre of football interest in West Yorkshire.

In Bradford there was an expectation that the trophy should be brought back to the town and it was considered anomalous that a team of Bradfordians could not win the competition given the extent to which ‘football’ had taken off with the emergence of new teams after 1875. This inevitably put pressure on Bradford FC, as the senior side in the district, to succeed.The failing of Bradford FC to win the Yorkshire Cup gave weight to the argument among members of other clubs in the district – which by 1878 comprised Bradford Albion, Bradford Caledonian, Bradford Rifles, Bradford Zingari, Bradford (Manningham), Bradford Juniors, Dudley Hill, Airedale, Bierley and Bowling – that the best talent was being excluded from representing the town in a single team. To what extent this amounted to prejudice on account of social background, friendship groups or partisan loyalty is difficult to say but it left players from other clubs in no doubt that they should enter their own team to fulfil their patriotic duty to their home town of being victorious in the final. (One factor that determined who played for Bradford FC was that it played its games at Apperley Bridge, hardly convenient to the majority of players a good proportion of whom lived in Manningham.)

At the beginning of the 1878/79 season a new side, Bradford United entered the Yorkshire Cup comprising players mainly from the Bradford Rifles club. Its challenge to the status of Bradford FC as the leading club in the district was given weight by the fact that the Bradford United team progressed further in the competition – Bradford FC was knocked out in the opening round at Wakefield Trinity whilst the Bradford United side was defeated in the second round at Leeds.

In April, 1879 agreement was reached between the members of Bradford United and the senior Bradford club that the latter should expand its membership to become more inclusive. What persuaded the Bradford FC captain Harry Garnett and the other leading personalities of Bradford FC to acquiesce was the prospect that the Bradford United players might otherwise be invited to play at the new Park Avenue ground rather than their own club, whose self-identity was that of being one of the aristocrats of Yorkshire rugby. In 1880 the enlarged Bradford Football Club merged with the reconstituted Bradford Cricket Club to become the Bradford Cricket, Athletic & Football Club and based at Park Avenue. Notwithstanding, the changes failed to have an immediate impact and it was not until 1884 that the Yorkshire Cup was secured, the eighth season of the competition.

The nature of football rivalry in the town

Other than Bradford FC and Bradford United, three more Bradford clubs entered the Yorkshire Cup in the early years including Bradford Albion, Bradford Juniors, and Bradford Zingari. The cup offered the possibility of glory (however unlikely that might be) and progress in the competition was considered a yardstick of standards for players to earn bragging rights. The rivalry of the original clubs was short lived owing to the restructuring of Bradford football between 1879-80 that led to the disappearance of Caledonian, the disbanding of Zingari in March, 1881 and the formation of Manningham FC in 1880. Albion disappeared in 1886 and the Rifles remained peripheral, depleted by key players joining Bradford FC. A key theme was that the nature of the rivalry between these clubs was essentially that between individual players.

The clubs who emerged in the 1880s were altogether different. In terms of social composition, they tended to have a far higher proportion of skilled working men. The other characteristic was that these clubs were defined by geographic affiliation and it didn’t take long before every village in the Bradford district had its representative. The Yorkshire Cup had the same allure and when Bradford FC finally won the competition in 1884 it encouraged the formation of yet more sides. By the mid-1880s there was already a defined hierarchy of clubs ranging from the two seniors in the town – Bradford FC and Manningham FC – to the feeder clubs who tended to play in the parks. Although there were rivalries between the players of the respective teams, the rivalry of the clubs now tended to be defined by their supporters.

In the absence of league competition, it was the Bradford Charity Cup that played a key role in the development of rivalries in the district and it should be recognised for its role in developing a football culture in the town. The junior clubs had a bit part in the Yorkshire Cup, gaining attention from participation in the early rounds and deriving credit from players graduating to the town club. The Bradford Charity Cup however allowed those clubs to taste glory and emulate the victory celebrations of their larger brethren.

There was a defined pecking order of clubs in the Bradford district but what characterised rugby in the area was the sheer strength in depth. So too, the number of teams was proof that Bradford was once very much a rugby town. We tend to believe that sport came of age in the modern era in terms of mass participation yet by 1895 there were more than one hundred rugby sides in the Bradford district. (That most of those had disappeared by the end of the century in favour of soccer was equally remarkable.) The rugby enthusiast was spoilt for choice. In addition to the rivalry of the seniors, there was strong competition at all levels with at least half a dozen decent junior sides in the Bradford district and it all amounted to variety and a rich football culture. Indeed, Bradford of the 1880s and 1890s can rightly claim to have been a sporting centre with well-established clubs catering variously to cricket, athletics, cycling, gymnastics and for that matter, chess. The Bradford Charity Cup reflected and contributed to the vitality of Bradford sport.

The small pot

In the immediate aftermath of winning the Yorkshire Cup, Bradford FC was active in charity fund-raising initiatives. One such event took place at Cardigan Fields in Leeds on 15 April, 1884 at which a Leeds & District XV played a Bradford & District side to raise money for the Leeds and Bradford Infirmaries. The following month, the Bradford Charity Cup competition was instigated by Bradford FC with the patronage of the Mayor, Isaac Smith as the club continued to bask in the glory of its Yorkshire Cup success.In the nineteenth century, sporting events had traditionally been associated with gambling and drink. As if to demonstrate the respectability of sporting activity, the athletic festivals that became increasingly prevalent in West Yorkshire from the 1860s – as indeed throughout the rest of the country – became closely associated with charitable fund-raising. In this way, sport was promoted as a force for good and for social unity rather than the sponsor of less virtuous behaviours. The link with charity also represented an alignment with the practice of the annual Whitsun galas at Peel Park which – after the final repayment in 1863 of debts arising from the purchase of the park – raised funds for the town’s infirmary.

In due course the connection between sport and charity, in parallel to that between athleticism and military preparedness, became institutionalised. In Bradford, the commitment to charitable support became an intrinsic component of football culture and from 1876 it was the focus of the annual contest between Bradford FC and a District XV team comprising representatives of other clubs.By the mid-1880s football charity cup competitions had become commonplace in industrial towns with such examples in Sheffield, Wendesbury, Blackburn, Bolton and Burnley. The most famous of all was the Glasgow Charity Cup which had been staged since 1876.

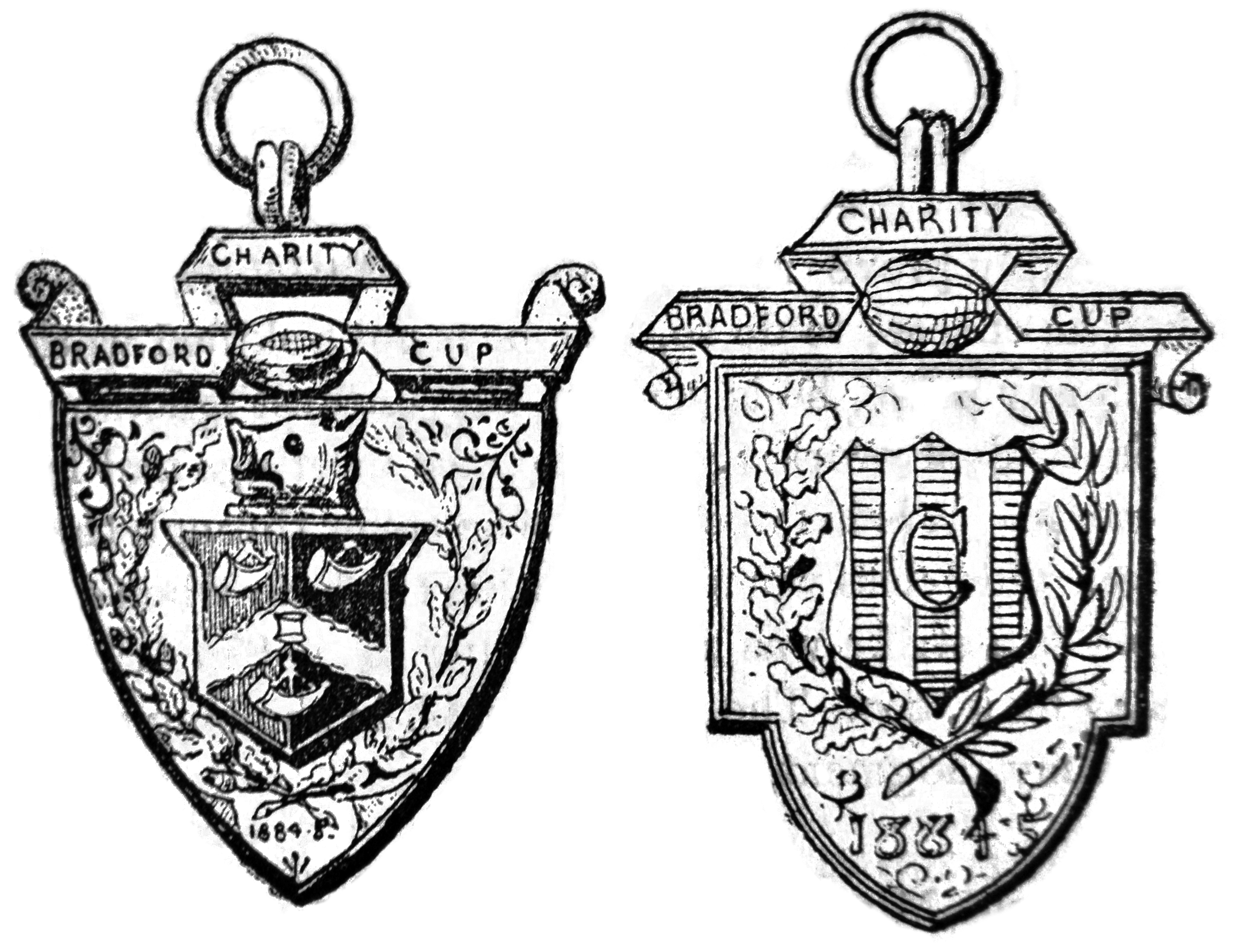

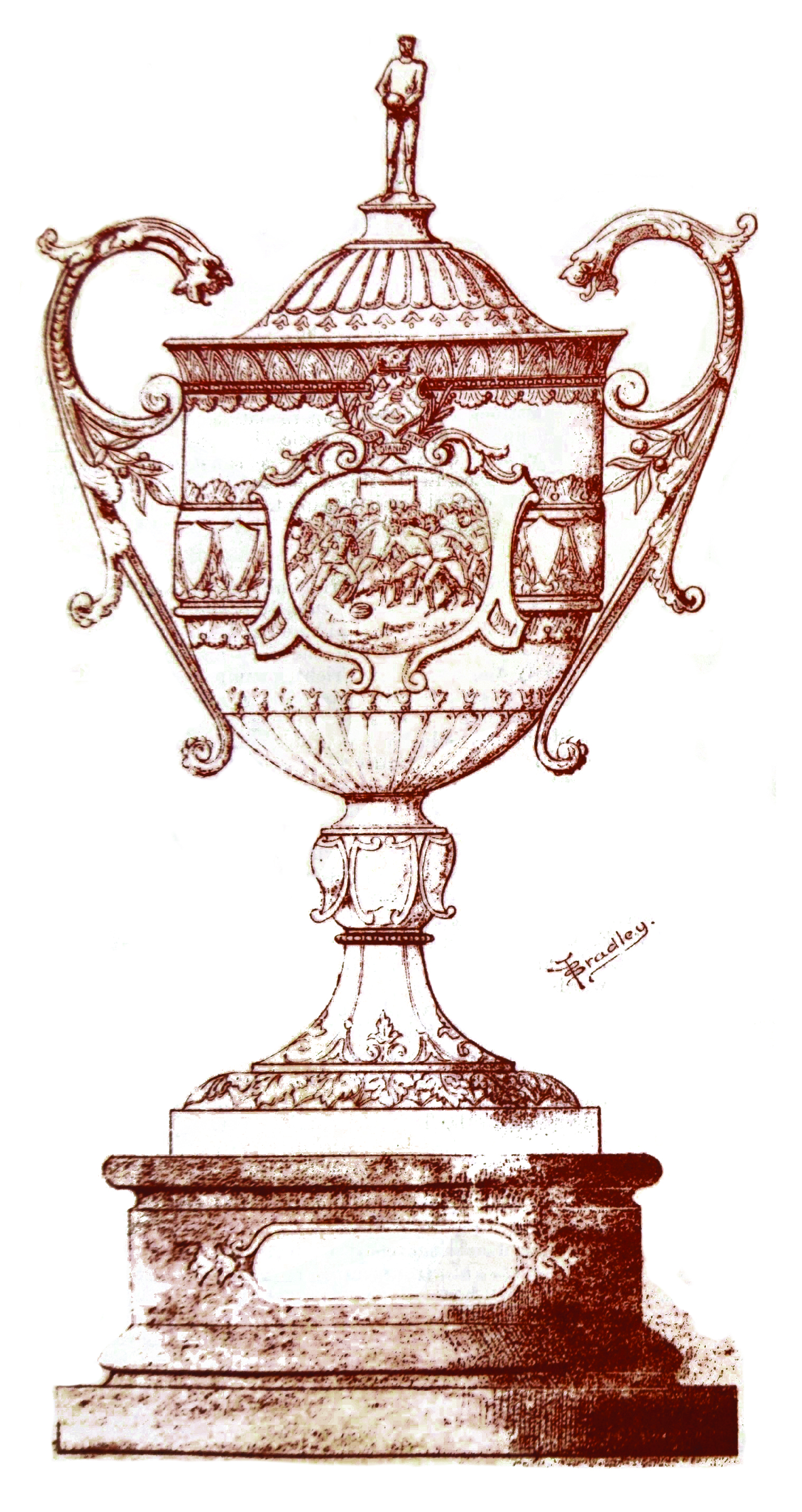

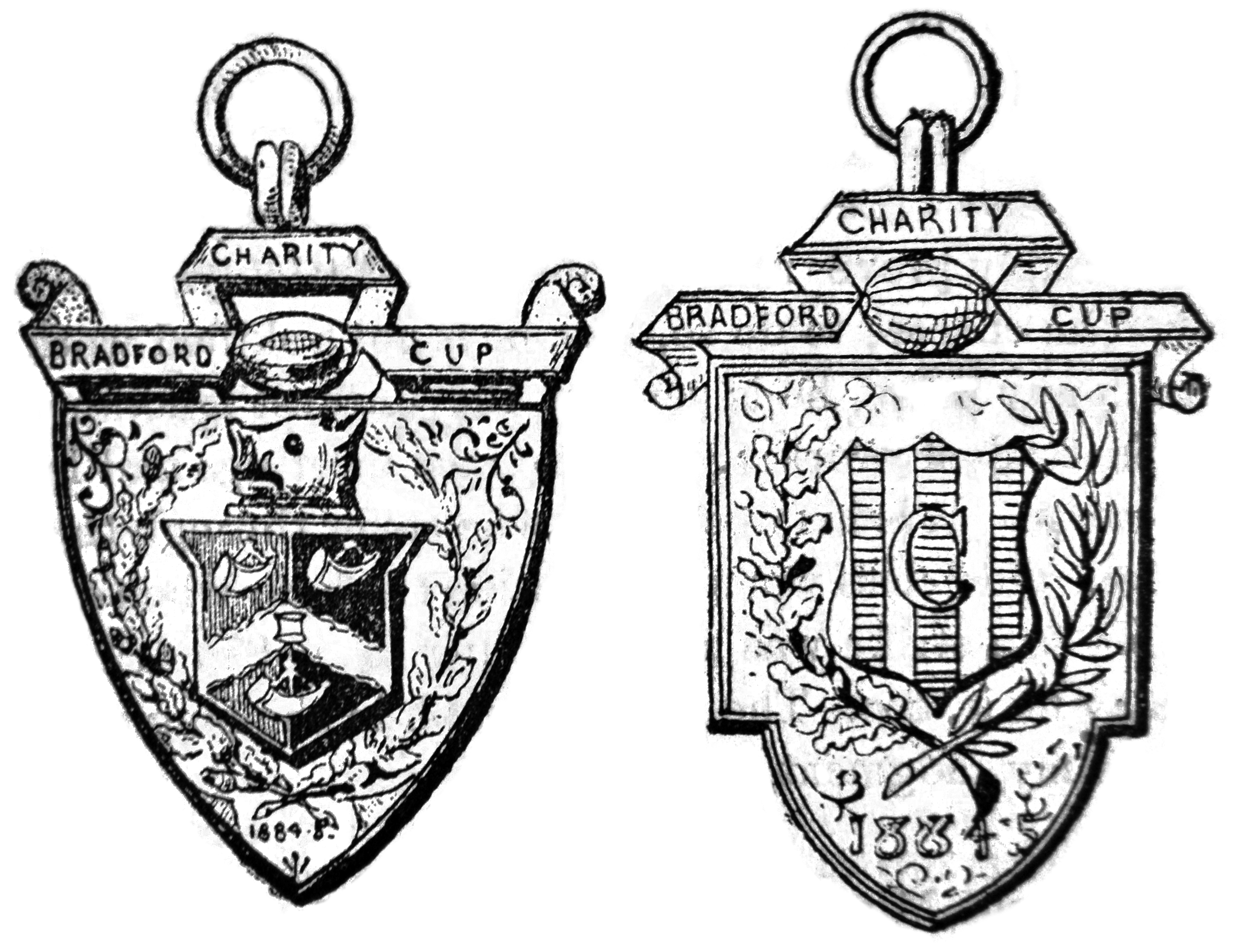

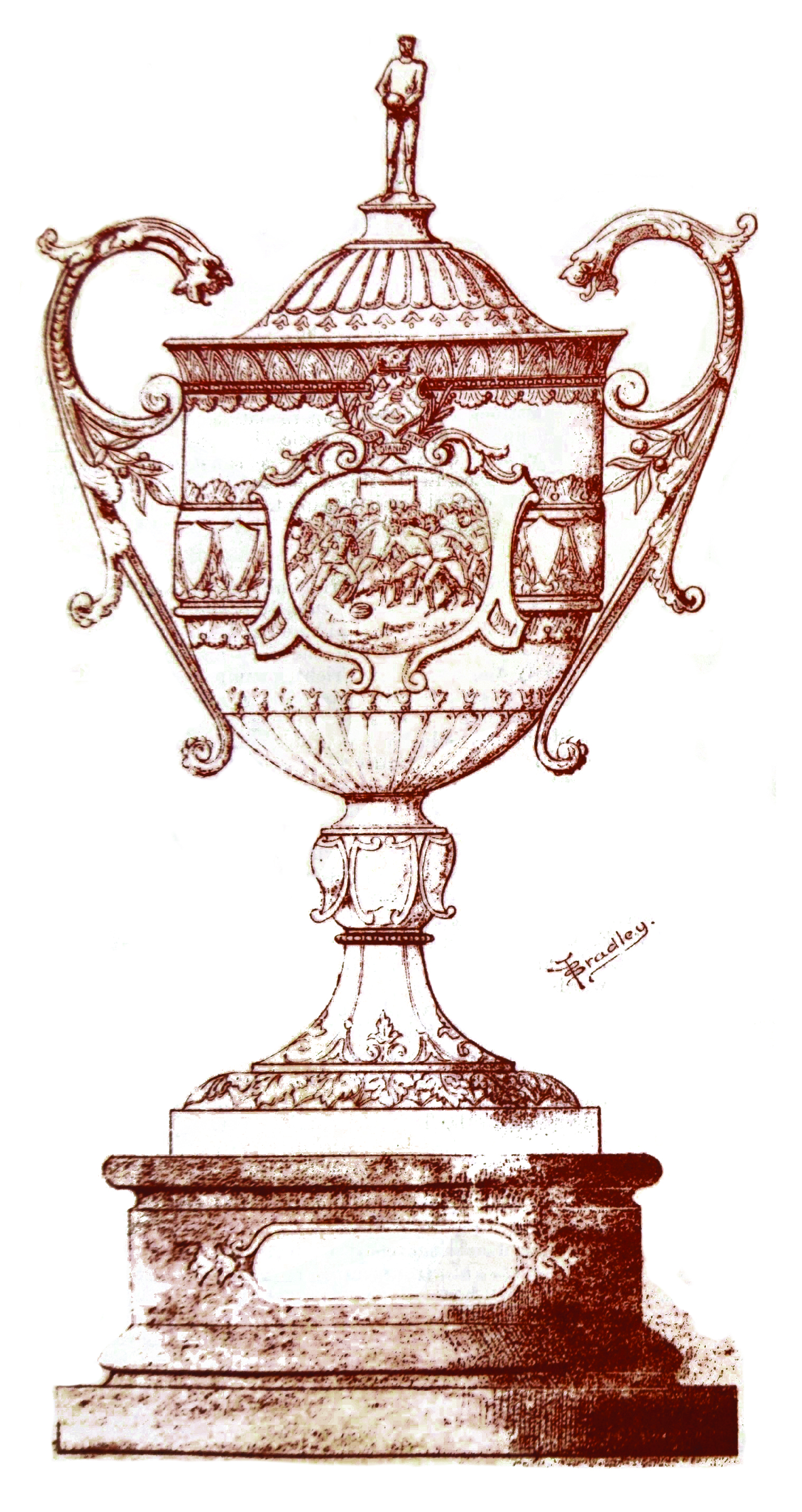

In common with the Yorkshire Cup, the FA Cup and the Rugby League Challenge Cup as well as the Keighley Charity Cup, the Bradford Charity Cup trophy was designed and manufactured by Messrs Fattorini of Bradford. The firm also manufactured the winners’ medals, description of which was reported each year in the local press with readers informed of the size, weight and composition. Even the change in design from a shield to a circular shape in 1892 was recorded. The Fattorinis proved adept at self-publicity and the medals were displayed in the firm’s shop window on Kirkgate, Bradford.

In September, 1906 the Northern Union Challenge Cup and Bradford Charity Cup trophies were rescued from the Alexandra Hotel where a fire had started in one of the reception rooms used by Bradford FC for official functions. At the time, the value of the two were quoted to be 60 guineas and 50 guineas respectively. The relative value of the trophy plainly demonstrates the importance attached to the competition at the time of its launch. Hence, although referred to as ‘the small pot’, the Bradford Charity Cup trophy sounds to have been anything but. The Bradford Daily Telegraph of 19 February, 1902 described it thus: ‘made of solid silver, 22 inches high with a football figure on the lid, and round the bowl are views of the Infirmary, the Eye & Ear Hospital, etc’. Interestingly this differs from the description in the Bradford Daily Telegraph of 28 July, 1884: ‘In the centre of the face is a representation of a football field, with two competing teams struggling for the ball, and goal posts and cross bar in the distance. A coloured shield, with the motto ‘Labor Omnia Vincit’ engraved beneath it, is placed above the centrepiece. The handles and stem are of delicate structure, and the latter rests on a substantial stand. The cup is richly decorated, and will be a handsome trophy of which the winners may well be proud.’

The Bradford Daily Telegraph of 14 June, 1884 specifically identified the Glasgow Cup competition as the inspiration and noted that the Glasgow hospitals had benefited by £5,000. It was reported that the Bradford competition was to be organised on the same lines with a governing committee comprising three members of the Bradford FC committee, four of the Joint Hospital Fund Committee and four representatives of the district. The competition was thus supervised on behalf of the Bradford Joint Hospital Fund in conjunction with the Park Avenue club. However, there was a certain pomposity about the motives of Bradford FC promoting its launch which had to do with the club wanting to demonstrate its charitable largesse as well as its paternal encouragement of football in the district.

The original concept appears to have been that the top four sides in the district should compete but doubts about whether this would attract public interest due to a gulf in standards may have led to entry being restricted to junior sides. The Bradford Daily Telegraph of 28 July, 1884 for example questioned whether it would ‘prove an effective means of raising money for the Infirmary unless the radius from which the teams will be drawn is very much widened.’ It was asked whether it was necessary to invite the likes of Wakefield, Halifax and Huddersfield to compete with Bradford FC but in the final event it was decided that it should be junior sides who entered to make it a more competitive contest. The decision probably suited Bradford FC which could underline its status as the leading side in the town by refraining from entry. Hence it was deeply symbolic that it was the Bradford FC ‘A’ team that entered the competition alongside the Manningham FC first team as well as junior clubs in the district. The two other entrants in the first season of the competition were Bingley and Cleckheaton.

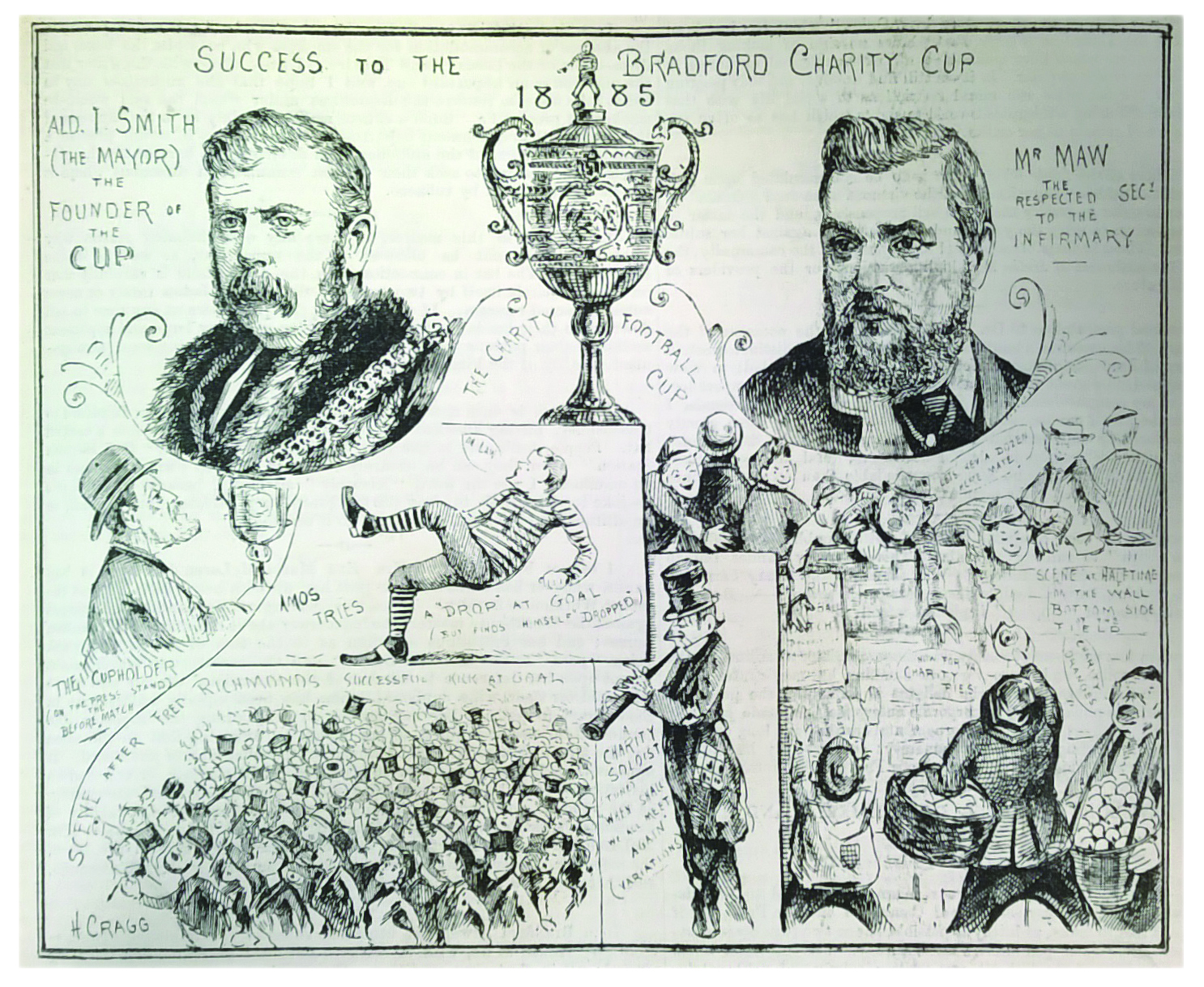

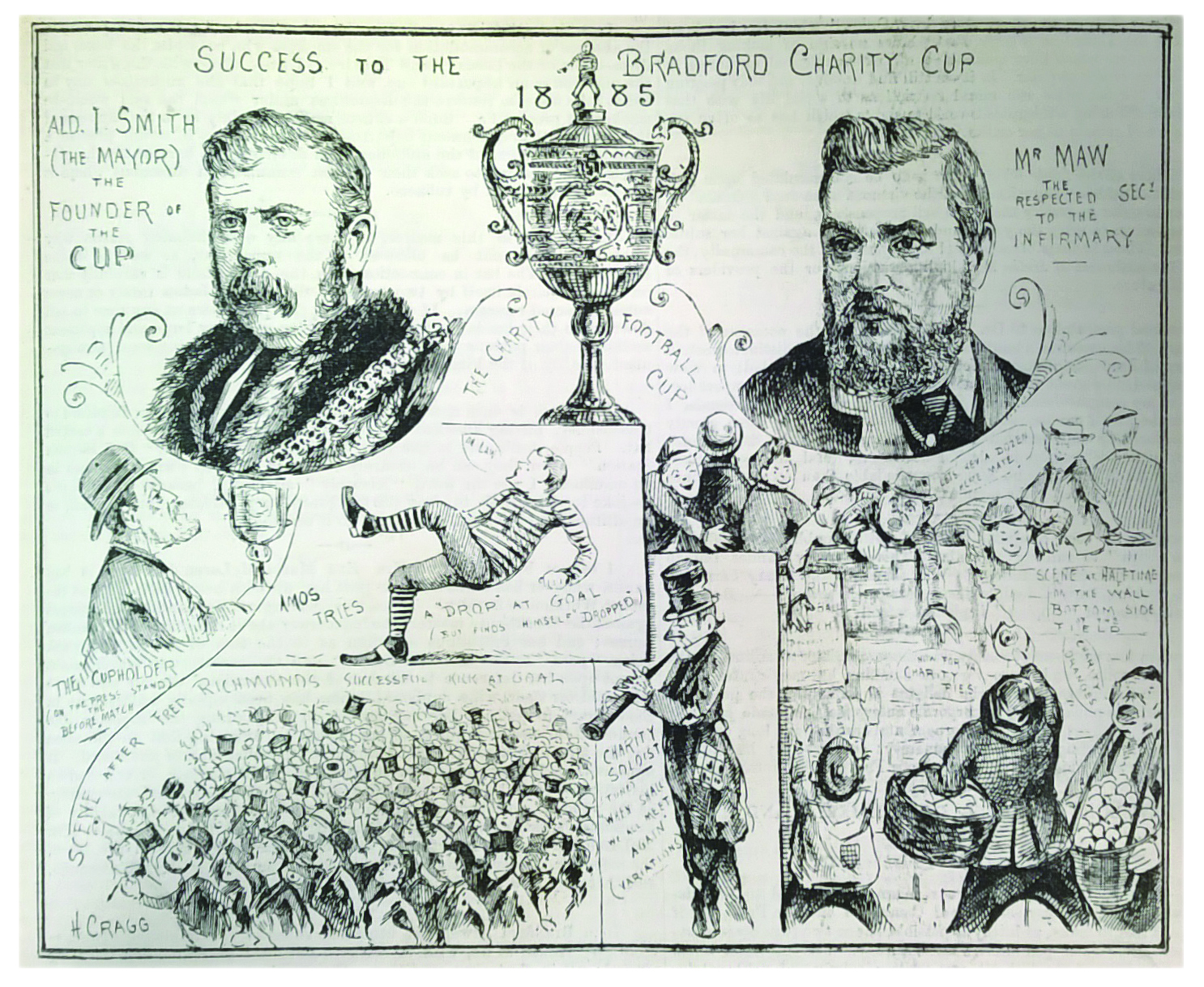

The chosen format proved successful in generating public interest and the inaugural final at Park Avenue in April, 1885 was well attended with a ten thousand gate and £170 receipts. This contrasted with the crowd variously reported as twelve and sixteen thousand who watched the Yorkshire Cup final at Cardigan Fields in Leeds the previous week (between Batley and Manningham) and that of ‘between five and six thousand’ who attended the comparable Wharncliffe Charity Cup final at Bramall Lane, Sheffield.

Manningham played Cleckheaton in that first final with the defeated semi-finalists being Bingley and the Bradford FC ‘A’ team respectively. Having been losing finalists in the Yorkshire Challenge Cup in 1885, Manningham FC were the clear favourites to win the Bradford Charity Cup but nonetheless it proved to be a close game. The Athletic News of 14 April, 1885 reported that ‘though not a ‘spite and malice’ match, (it) was about as close as they get things even in Yorkshire. At the end of the original term for play, each side had scored six minor points. In an extra 20 minutes Fred Richmond dropped a goal, and thus won the match.’

The cup success was cherished by Manningham supporters and in June, 1885 it was even commemorated by a floral display in Lister Park by Frank Richmond – Fred’s brother and himself a member of the winning Manningham team – whose father was head gardener of the park. It continued a theme from the previous year’s display which had been a tribute to the Yorkshire Cup success of Bradford FC.The Athletic News was effusive about the success of the Bradford Charity Cup in its first season and on 14 April, 1885 had reported that ‘the Bradford Charity Cup competition in which only four clubs engaged, will realise considerably over £300 for the purposes intended. Is there any other sport in kingdom which raises half so much for charities as football? If so, we do not know that particular game.’ It was not only that the competition had been successful with fund raising (NB the £300 claimed would have been the gross gate receipts as opposed to the net contribution after deduction of expenses). The competition had also helped refute criticism that rugby was associated with rough play: ‘The Mayor of Bradford, in presenting his Charity Cup to Manningham, mentioned that although there had been an immense amount of football in the neighbourhood, there had not been a single case of an injured football player being taken to the Bradford Infirmary.’

The Leeds Times of 19 September, 1885 reported that the Bradford Charity Cup prompted imitation competitions in Dewsbury, Halifax and Huddersfield. Indeed, such was the interest in the competition that in October, 1885 one enterprising trader was even advertising score cards for the Bradford Charity Cup as well as the Yorkshire Cup in the press. In the final reckoning therefore, the impact of the Bradford Charity Cup had wider reach than the confines of the Worstedopolis.

In the second season, 1885/86 the number of entrants was expanded to sixteen and comprised the following to become a truly district-wide competition: Bingley; Bowling; Bradford ‘A’; Bradford Trinity; Buttershaw; Cleckheaton; Dudley Hill; Greengates; Heaton; Keighley; Liversedge Old; Manningham; Manningham Rangers; Queensbury; Saltaire; Shipley and Skipton. Other participants later included Bowling Old Lane, Farsley, Idle, Low Moor St Mark’s, Silsden, Wibsey and Windhill. The stipulation was that they came from the area in which the Bradford hospitals drew their patients.

On 14 September, 1886 Alfred Pullin commented in the Athletic News that ‘Junior Challenge Cup competitions are becoming as thick as mushrooms. There are the ‘Wakefield Express,’ the Huddersfield, the Halliday (Huddersfield), the Halifax, the Bradford Charity, and the Wharfedale & Airedale Observer competitions all on the tapis. The Wharfedale is a new institution, and the cup is now being manufactured by Messrs. Fattorini & Sons, the well-known athletic prize manufacturers.’ It marked the high point of the fashion for charity cup competitions in the region and the enthusiasm of local newspapers to sponsor such competitions revealed their popularity. (NB entrants in the Wharfedale & Airedale Cup from what now constitutes the Bradford Metropolitan District included Bankfoot, Dudley Hill, Idle, Ilkley Rovers, Keighley Shamrocks and Wibsey.)

The winners

The Manningham FC side proved too strong and won the competition during the first two seasons under the captaincy of Harry Archer and William Fawcett respectively. Manningham’s defeat of the Bradford ‘A’ side in the semi-final of the Bradford Charity Cup in April, 1886 – a game witnessed by a crowd of eight thousand at Park Avenue – was a defining moment as it represented the first time victory had been achieved by Manningham against representatives of the senior club. Manningham FC magnanimously withdrew from the competition after the club’s victory over Bradford Trinity in the 1886 final and this allowed the club to make a point about its pedigree. According to the Athletic News of 25 May, 1886 ‘Manningham have decided that in future the ‘A’ team, and not the first team, shall compete. As Bradford first is barred, Manningham first have barred themselves, considering their ‘A’ team quite as well qualified as the Park Avenue ‘A’ team to represent the club.’ Manningham FC remained anxious to demonstrate its charitable largesse and in November, 1886 the recently opened Valley Parade was made available to host the derby second round tie between Shipley and Bingley.

Notable is that Manningham FC’s decision to withdraw was criticised, no doubt emanating from Park Avenue where there was little love lost for the emergent rivals to Bradford FC. The Athletic News of 8 June, 1886 for instance commented that ‘the Bradford Charity Football Cup competition has received a knock-down blow by the decision of the Manningham FC to allow their second team to represent them in next season’s contest… The general opinion is that it would have more patriotic for the Manningham first fifteen to have tried for the cup another year and then, after winning it, as they probably would do, to hand it over to the Charity Committee for competition under revised arrangements.’

The Bradford Charity Cup had certainly been popular with Manningham supporters and the club’s withdrawal would have impacted on the finances of the competition; a crowd of seven thousand had attended the second tie between Manningham and Cleckheaton at Carlisle Road in December, 1885. In April, 1886 it was also decided by the organising committee that the competition should be restricted to only eight sides, presumably on account of difficulties incurred during the 1885/86 season to arrange ties and the marginal revenue derived. Already the Bradford Charity Cup was facing constraints on its ability to generate funds.

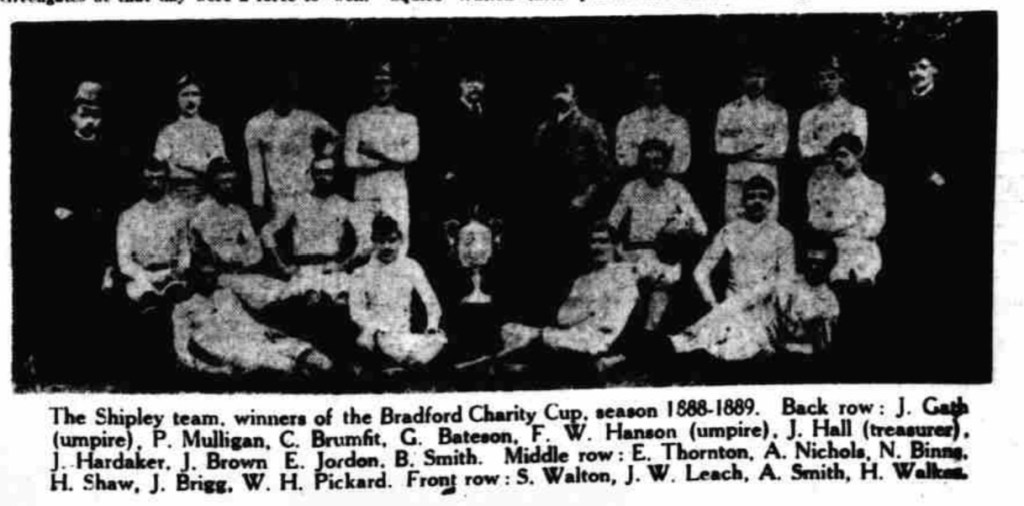

During the eight seasons from 1886/87 to 1893/94 no fewer than six different clubs won the trophy and a total of eight different sides appeared in the final, evidence that it was a fairly open competition. The reserve teams of Bradford FC and Manningham FC surprisingly made little impact. In 1890 the Manningham ‘A’ team reached the final but was unable to play on account of the club’s Easter tour of South Wales; opponents Shipley FC refused to re-arrange the game and Buttershaw FC substituted for Manningham to set up a re-run of the 1889 final.

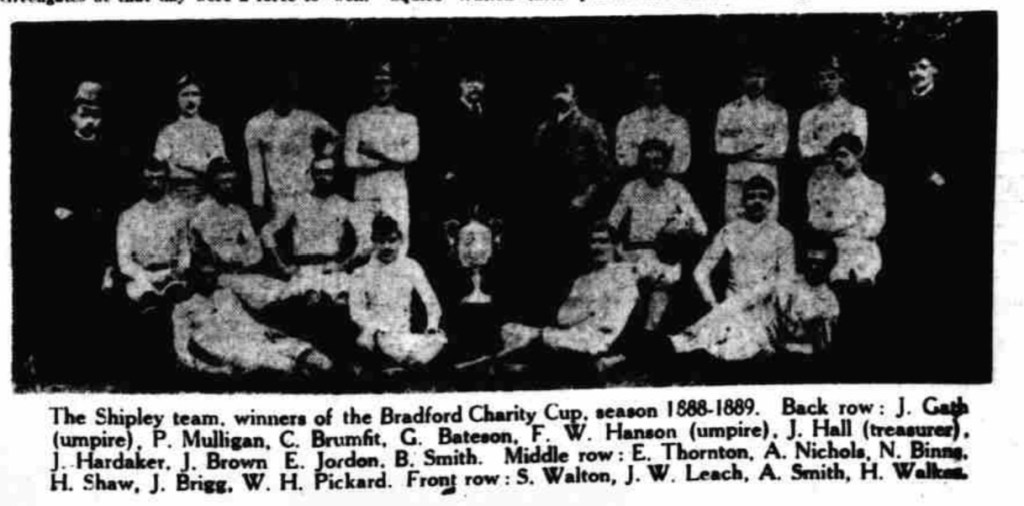

During the ten years of the Bradford Charity Cup, Manningham FC, Bowling and Shipley won the trophy on two occasions. Shipley and Buttershaw boasted the most appearances in the final (three) but Shipley could claim the best record with only one defeat.

| Bradford Charity Cup Finalists – Rugby Union |

|

|

| Year |

Winners |

Runners-up |

| 1885 |

Manningham |

Cleckheaton |

| 1886 |

Manningham |

Bradford Trinity |

| 1887 |

Cleckheaton |

Shipley |

| 1888 |

Buttershaw |

Cleckheaton |

| 1889 |

Shipley |

Buttershaw |

| 1890 |

Shipley |

Buttershaw (NB Official records disclosed ‘beaten’ finalists to be Manningham who were replaced by Buttershaw due to being unable to participate.) |

| 1891 |

Bowling |

Bowling Old Lane |

| 1892 |

Bowling |

Windhill |

| 1893 |

Bowling Old Lane |

Low Moor St Mark’s |

| 1894 |

Yeadon |

Windhill |

The demise of the competition

In its early years, the Bradford Charity Cup was popular and it was reported that the early finals at Park Avenue were attended by five figure crowds. Even though attendances declined they were reported to have remained in excess of five thousand for the final ties.

During its existence the Bradford Charity Cup was said to have raised a total of £1,116 for charity. By 1894, when the competition was abandoned the proceeds were reported to be negligible. Contrast this with the record of the Glasgow Merchants’ Charity Cup that was cited as the inspiration and which continued until 1966; during its ninety years of existence it is estimated to have generated a total of £350k whilst in the corresponding seasons, 1884/85 to 1893/94 a total of £8,860 was donated to charity. (From Remembering Us Year after Year: The Glasgow Charity Cup 1876-1966 by Wray Vamplew, University of Stirling (2008).)

The gate proceeds at the Bradford Charity Cup final in 1887 were reported to have been £158 with a crowd of twelve thousand; these fell to £116 the year after and then to £111 in 1889 when there was a reported crowd of 8,000. In 1891 and again in 1893 the finals were said to have attracted only six thousand. Accordingly, the net revenues must have declined significantly by 1894.

Of course, it was not just that gross income was declining. Clubs would have been anxious to recoup their own expenses and there is a good chance that the financial arrangements were renegotiated with the management committee of the competition. There were also fixed costs associated with staging the semi-finals and final such as advertising and the cost of medals for the winners. (The practice was that medals were funded by public subscription rather than gate receipts.)

A number of reasons may be given for the demise of the competition. The first is that after 1892, junior clubs in the district had become focused on success in league competition and the second is that after 1891 football gates had suffered the economic effect of lower disposable incomes, a consequence of trade depression. The finalists in 1894 – Yeadon and Windhill – were considered to be among the smaller clubs in the Bradford orbit and unlikely to attract a decent attendance.

The relatively low crowd for the third round Yorkshire Cup tie between Bradford FC and Bingley FC in March, 1894 demonstrated that spectators were more interested in big name fixtures; even a cup game could only attract eight thousand to Park Avenue. Besides, after 1890 most fixtures involving the two senior Bradford clubs against local opposition were for fund-raising purposes to avert their financial implosion and the novelty value had disappeared. Equally, whilst the first round cup tie between Bradford FC and a local junior team, Wibsey FC in March, 1894 undoubtedly had a romantic appeal it was something of an inconvenience for the senior side to have to go through the motions.

The one contest likely to draw a large crowd was that between Bradford FC and Manningham FC yet their focus was league competition. Neither wanted the distraction or implications of a showdown cup tie, particularly after the controversy of 1887 involving the postponed Yorkshire Cup match between the two at Park Avenue. Besides, their participation would have been at the expense of the juniors and counter-productive to wider participation and the success of smaller sides.

(Image above courtesy of Ron Watson)

However, it was not only the loss of enthusiasm among spectators and the organising committee, but among the clubs themselves. The Bradford Daily Telegraph of 4 April, 1893 mentioned that larger sides were withdrawing from the competition. Similarly, in its report of 27 January, 1894 of the Windhill v Idle semi-final the same paper bemoaned the fact that there were only eight entrants. Furthermore, none of those sides contesting the Bradford Charity Cup in 1893/94 could be described as having any sort of pedigree – Farsley, Idle, Low Moor, Saltaire, Silsden, Wibsey, Windhill and Yeadon – most of whom had abandoned the Wharfedale & Airedale Cup.

Clubs faced an opportunity cost from participation in the competition by virtue of donating gate receipts to charity and this would have been particularly felt by those reaching the semi-finals. Nor was there an economic benefit to the finalists who lost the opportunity to stage an ordinary fixture on Easter Monday, one of the prime dates in the football calendar.Alfred Pullin had written in the Athletic News on 9 November, 1886 that ‘With Manningham’s withdrawal the competition has become a barren affair, and such clubs as Cleckheaton and Liversedge are, I hear, not likely to go in for it another year. What was thus a high class competition will, therefore, sink to a junior’s level, and, seeing that the institution is a charitable one, this is much to be regretted.’

The singular criticism of Manningham FC was somewhat unfair; it failed to acknowledge the lack of a critical mass of clubs of both equal and sufficiently high standard in the Bradford district to make the contest competitive and appealing to the public.

Another matter that may have dissuaded the organising committee from continuing with the competition was that it was attracting the wrong headlines. In March, 1889 for example, the Shipley player Lister Wade died of his injuries in the semi-final tie with Saltaire FC at Park Avenue. The Bradford Daily Telegraph of 9 March reported that several rough incidents had occurred in the second half and that he had been ‘recklessly charged by two opponents’ and forced to leave the field with ‘bleeding from the ears’. (As if to underline the perils of the sport generally, on 12 March, 1889 it was reported in the Bradford Daily Telegraph – and widely circulated in the regional press – that a spectator at the Bradford / London Scottish game at Park Avenue had died having been ‘taken ill supposed from excitement’ – by which it presumably meant a heart attack.)

In April, 1893 the final between Bowling Old Lane and Low Moor St Mark’s was overshadowed by violence that involved one of the Low Moor players assaulting an opposing player. A fracas then ensued that led to the Low Moor team leaving the field and refusing to continue the match.

In a letter to the Bradford Daily Argus of 14 May, 1907 the former Manningham FC captain, William Fawcett (who was voicing opposition to the merger of Bradford City AFC with Bradford FC) blamed Bradford FC for the demise of the Bradford Charity Cup. He claimed of the Park Avenue club that ‘It was through them the Charity Cup lost its popularity, which ought to have brought at least £1,000 a year, and the pantomime carnival started at Valley Parade was soon lost to the charities when it went to Park Avenue.’ The reality was that the Bradford Charity Cup had lost its momentum and fallen out of fashion; The Athletic News of 15 April, 1901 later reflected that ‘the fever for cup competitions in a measure subsided’.

Fawcett’s comments spoke louder about partisan sentiment in Bradford. Notable however was that opponents of merger among the Bradford City membership were at pains to discredit the charity fund-raising credentials of the Park Avenue club. It was a subtle illustration that even in 1907 a notional commitment to charitable giving was a matter of self-respect in Bradford sport. (In February of that year the annual Pantomime football event had been reinstituted at Valley Parade to raise money for local hospitals, a fixture that had originated as a rugby game in 1891. In accordance with tradition it featured Bradford City players and local panto stars with everyone attired in fancy dress, described by the Bradford Daily Telegraph as a burlesque football match.)

The heritage of the Bradford Charity Cup

The Bradford Charity Cup in its original format between 1884/85 and 1893/94 symbolised the emerging football culture in Bradford, a phenomenon that captivated public interest and behaviours. The sport was elevated from being a form of recreation or just a game. For that matter it became more than a burgeoning entertainment business. Rugby football had become fashionable and began to define for itself a new role in the life of the town, celebrated for its perceived contribution to social cohesion, providing a common identity between classes. The sport derived respectability from its declared commitment to charitable giving that allowed it to counter objections about roughness, gambling or commercialism including charges of veiled professionalism. Support for charity allowed sport to be promoted as a force for good that additionally promoted the benefits of healthy activity and assisted the military preparedness of the town’s young men.

The Bradford Charity Cup also conferred importance to The Bradford Cricket, Athletic & Football Club which exercised self-interest as patron of the competition. Through its launch of the Bradford Charity Cup and the staging of final ties at Park Avenue, Bradford FC was given another opportunity to remind people of its primacy and the hierarchy of clubs in the town. (The sponsorship of cup competition for self-interest was later imitated by Manningham FC who launched the Manningham Challenge Shield competition to promote links with local rugby clubs in 1900. Likewise, in 1927 the Bradford Park Avenue Supporters Club launched its own cup competition for school soccer teams, again to encourage links and support.)

The fixture between the Bradford Rifles and the Leeds Rifles (contested by members of the respective volunteer corps) at Park Avenue in December, 1886 epitomised the spirit of the age with football embracing national and local patriotism, civic identity and charitable giving. The late 1880s was the high point of the charitable ideal; it was a time when the sport was in its infancy, when clubs had the profits to contribute and were not overburdened with other financial liabilities.

Another dimension to the charity fund raising was civic rivalry and the pride conferred to Bradford sportsmen able to boast about their charitable credentials, something that continued into the twentieth century. An example of this is provided in the report of the meeting of the Management Committee of the Bradford Cricket League in August, 1912. The Yorkshire Post of 24 August, 1912 reported that ‘the question was raised whether anything should be contributed to Leeds charities given that some of the clubs in the competition were from the Leeds District. The Chairman: Leeds has a Charity Cricket Competition, hasn’t it? The Delegate: No. The Chairman: Then Bradford is setting a good example.’ (Charity fund raising continued to be a means of mobilising civic pride in Bradford. Possibly the best example of this was the cumulative success of the various appeals that originally predated World War One and which eventually reached the £500,000 target for the new Royal Infirmary in 1934.)

The notional commitment to charitable giving remained an intrinsic component of self-identity among Bradford football clubs for the next thirty years even though amounts raised were relatively insignificant. After World War One, in Bradford at least, the principle of charitable support had to be sacrificed to the pressing issue of financial survival and the self-preservation of the clubs themselves. Even so, the tradition continued into the inter-war period of gate receipts from pre-season friendlies at Park Avenue and Valley Parade being donated to charity. More recently, the enduring efforts of Bradford City supporters in the last thirty years to raise money for the Bradford Burns Unit has much in common with the efforts of Victorian predecessors to generate sums for the town’s infirmary.

The Northern Union competition

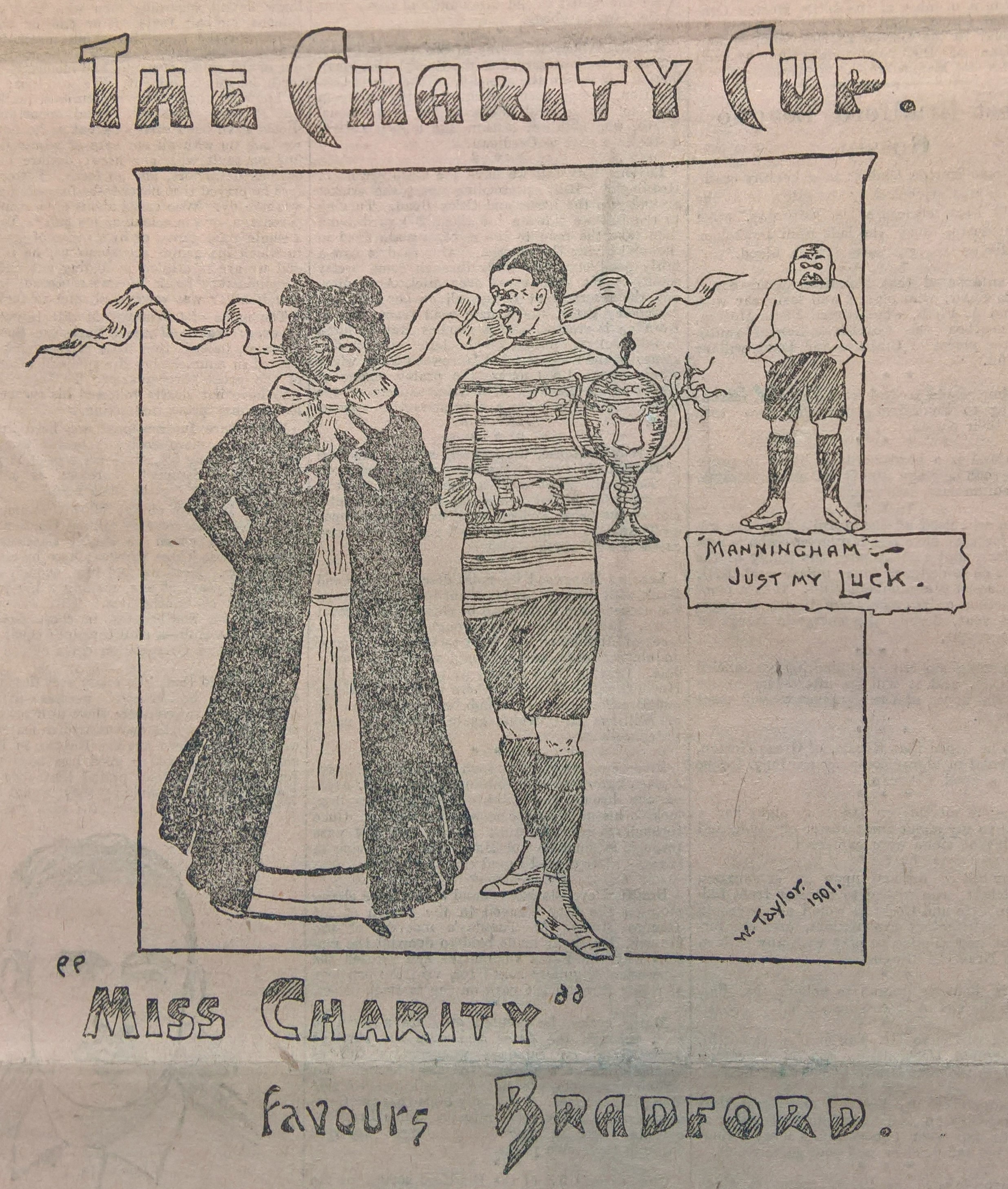

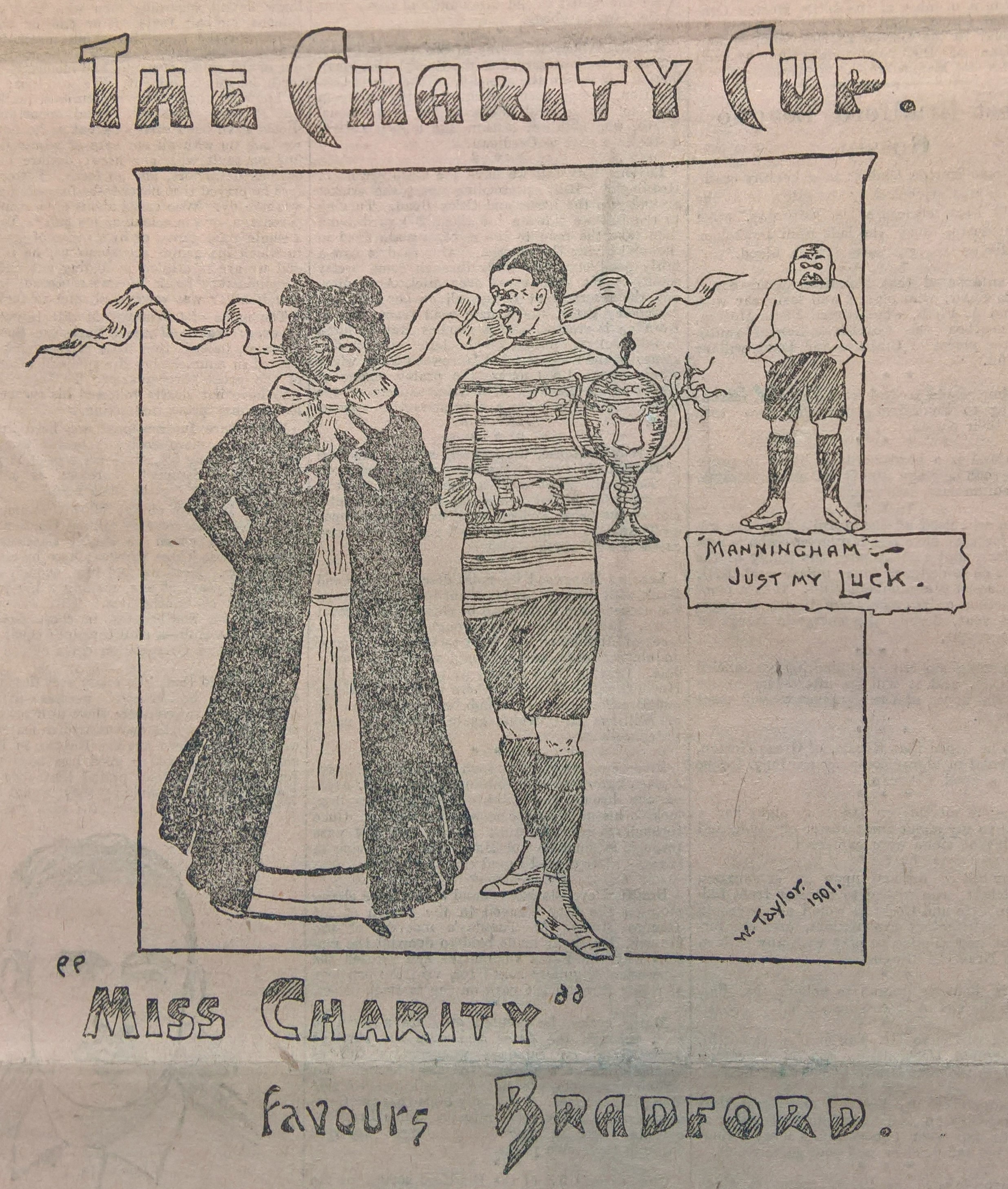

The Bradford Charity Cup had a strong emotional appeal, as confirmed by subsequent attempts to revive the competition prior to World War One including an extension of the format to cricket and soccer. In 1901 the competition was revived with the encouragement of the mayor, William Lupton with a single showpiece game between Bradford FC and Manningham FC. Lupton had been a member of Bradford FC at Apperley Bridge and, like Isaac Smith before him, may have identified the revival of the competition as a way to define his legacy as mayor. The trophy was retrieved from the Bradford Art Gallery where it had been on display and the Yorkshire Evening Post of 13 April, 1901 reported that ‘an effort was made to revive the utility of the cup as a money-earning asset’. Nevertheless, despite good advertising there was only a ‘moderate attendance’, generating in the region of £50.

Yorkshire Sports cartoon 20 April, 1901

Plans to repeat the competition the following season became embroiled in the politics of the Northern Union and the refusal by members of the Yorkshire Senior Competition (the second division) to stage games with the breakaway premier division. Manningham FC in particular were bitter about having been cast aside in the lower tier despite having been champions of the inaugural Northern Union league competition in 1895/96. Notwithstanding, the Manningham FC committee lobbied for the opportunity to contest the trophy with Bradford FC in 1902 and following the intervention of the Bradford mayor, the YSC lifted its embargo for the game to be played.

The match on 1 April, 1902 proved to be the final competitive fixture between the two senior Bradford clubs. By this stage the gulf in class was pronounced and Bradford FC were comfortable winners in front of a seven thousand crowd at Park Avenue. Within weeks the Manningham FC leadership was actively planning to stage Association football at Valley Parade that led to the eventual launch of Bradford City AFC in 1903.

| Bradford Charity Cup Finalists – Northern Union |

|

|

| Year |

Winners |

Runners-up |

| 1901 |

Bradford FC |

Manningham FC |

| 1902 |

Bradford FC |

Manningham FC |

The ascendancy of Association football in Bradford led to proposals to launch a Bradford Charity Cup competition for local soccer teams in 1903. Recognising this as a challenge to their own code and no doubt aggrieved by the suggestion that the original trophy should be awarded to an Association club, the Bradford & District Rugby Union (the local governing body of the Northern Union) responded by organising a competition for its own members. My belief is that this was at the instigation of Bradford FC, anxious to promote rugby to counter the attraction of soccer – made even more fashionable now that the city had a Football League side at Valley Parade.

By 1903 however, there was only a handful of local Northern Union sides (and for that matter only one affiliated to the Rugby Union). Furthermore the membership of the Bradford & District Union was weighted towards outlying areas, principally Keighley as well as Pudsey and villages bordering Halifax. The clubs themselves were much lesser entities than their predecessors who competed in the original Bradford Charity Cup and the revived competition was thus a pale imitation of the first. It could be said that the primary purpose of the competition was less to do with charity fundraising and that it was more about keeping the game of rugby alive in Bradford. What a contrast to the situation less than ten years before!

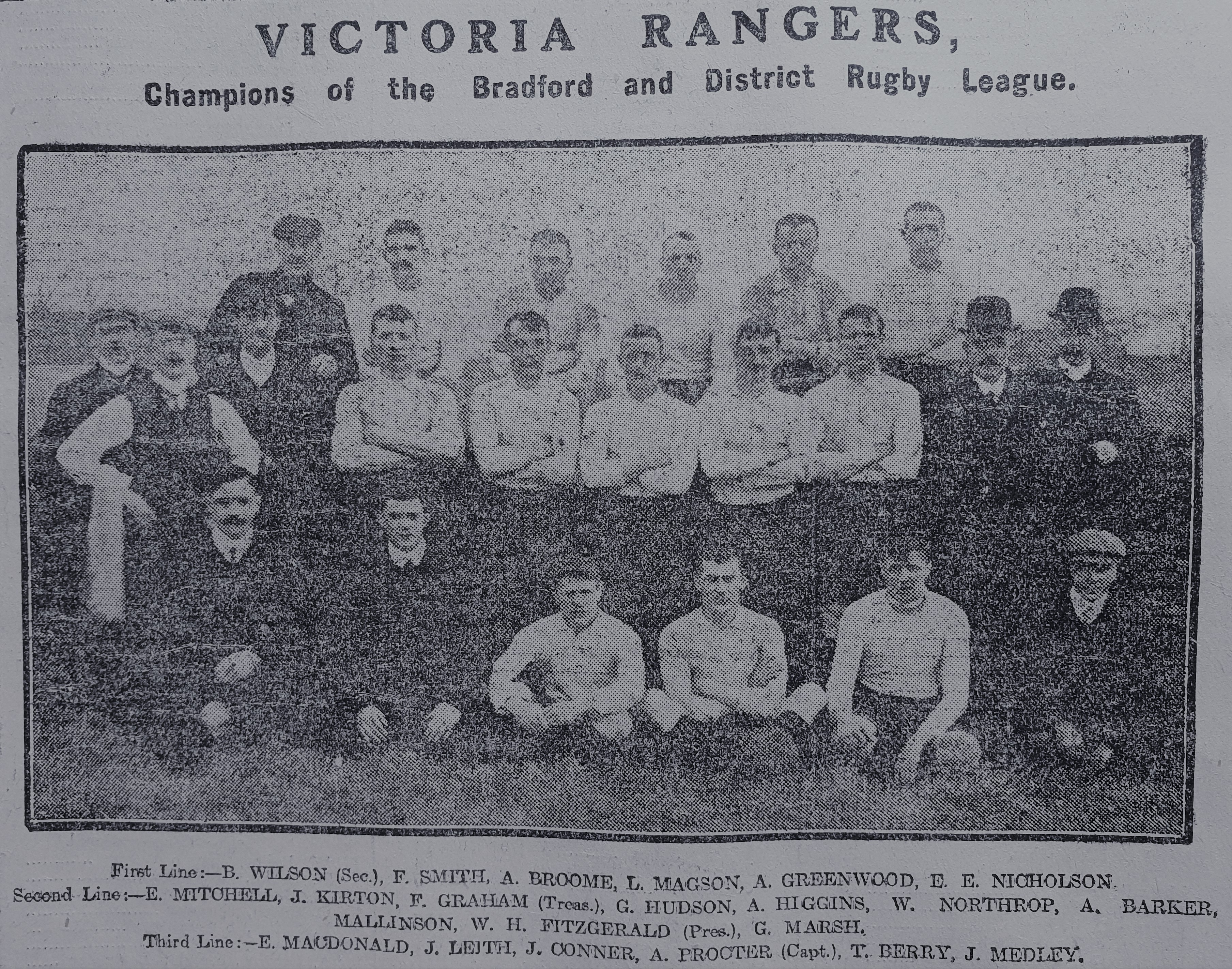

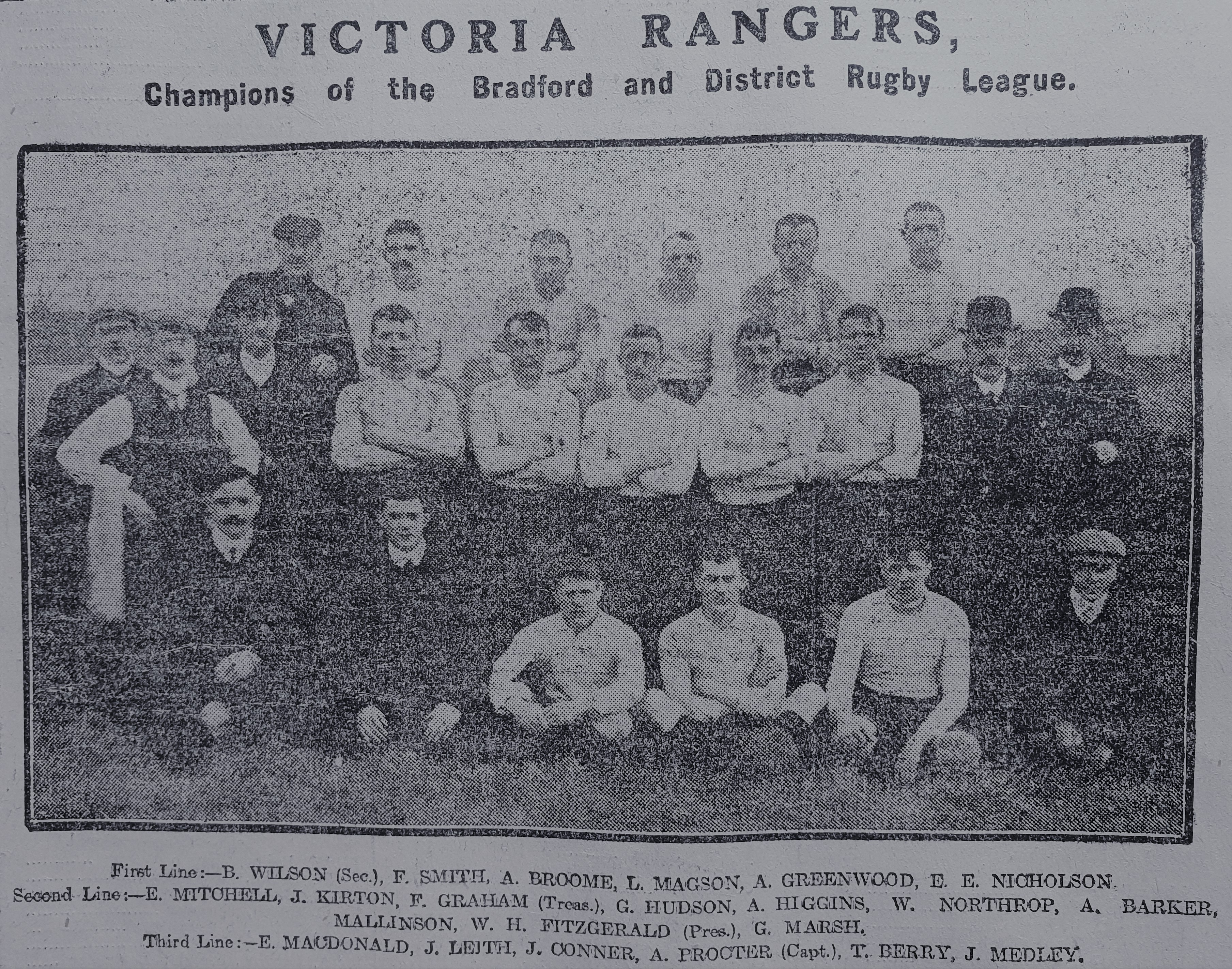

The organisation of a Bradford Charity Cup competition in 1903/04 was very much a last minute affair and it was eventually decided that the winners of the first and second divisions of the Bradford & District Rugby Union – Pudsey Clarence and Shipley Victoria respectively – should play a deciding match on Easter Monday at Greenfield, the ground at Dudley Hill adopted by the phoenix Bradford Northern club in 1907. On that occasion, Pudsey Clarence defeated Shipley Victoria in what must have been a fairly low key event for such a magnificent trophy. The competition was later played on a conventional knock-out basis with finals staged at Park Avenue and on Easter Monday, 1905 the trophy was won by Victoria Rangers, considered the leading Bradford-based amateur side of the time.

The following season, in January, 1906 an impressive seven thousand crowd saw Bradford FC ‘A’ team defeat Buttershaw after having beaten Hebden Bridge in the semi-final. In order to optimise gate receipts, the Bradford club stipulated that all members should pay to attend the game – hitherto the practice was that membership conferred free admission to all fixtures. In December, 1905 there was an appeal for public subscription to defray the cost of winners’ medals. The measures helped the competition generate total net proceeds of £55 and in November, 1906 the Bradford & District Union declared its target of raising £100 in the 1906/07 season. However, this objective seems unlikely to have been achieved and it was unfortunate that the timing of the final on 1 December, 1906 coincided with the Yorkshire Cup Final in which Bradford FC defeated Hull KR.

The abandonment of rugby at Park Avenue in the so-called ‘Great Betrayal’ of 1907 led to the retention of the Bradford Charity Cup trophy by The Bradford Cricket, Athletic & Football Club. The last rugby club to hold the original cup was Victoria Rangers who defeated the Saville Green club. Not only was the Bradford & District Rugby Union left without a charity cup trophy to award but it was denied the use of Park Avenue, the traditional home of rugby in the city.

In 1907/08 the home of the Wyke club was adopted as an alternative venue for the Bradford Charity Cup final. Additionally, in August, 1907 the Halifax Charity Cup trophy (with a value deemed to be 50 guineas) was offered to the Bradford & District Rugby Union on condition that one third of all semi-final receipts, plus the whole of the final receipts net of club expenses be provided to Halifax charities.

Although a Bradford Charity Cup competition continued in existence for local (Northern Union affiliated) rugby clubs it was alongside two other cup tournaments, the Halifax Charity Cup and the Bradford Challenge Cup. Likewise, Shipley based clubs also competed for the Keighley Charity Cup and there was the seeming anomaly of Stanningley FC winning the Bradford Charity Cup in 1908 and 1909 and Victoria Rangers (of Bradford) the Halifax Charity Cup in 1908/09. Not surprisingly, amidst of all this the Bradford Charity Cup competition lost prominence. In October, 1909 the Bradford & District Rugby Union handed back the Halifax trophy to the Halifax Charity Committee, presumably because competition for the trophy similarly had limited appeal. The retention of the trophy by the Park Avenue club was a sensitive matter and it is unlikely that the replacement trophy for the Bradford Charity Cup was equally prestigious as its predecessor or that of the Halifax equivalent. To all intents and purposes, the loss of the original trophy in 1907 fatally undermined the pretence of a charity cup competition for Bradford rugby clubs and the contest continued more as a statement of the survival of Northern Union football in Bradford. By 1909/10 there were only seven entrants in the final Bradford Charity Cup competition that was won by Northern Rangers, nursery side of Bradford Northern RFC.

Although the final between Stanningley and Victoria Rangers in January, 1909 was attended by a crowd of two thousand at Birch Lane (the new home of Bradford Northern), the net proceeds are unlikely to have exceeded £20. The ascendancy of Association football in Bradford was by now undisputed, exemplified by the case of Victoria Rangers who had for a long time dominated local rugby. To my knowledge the earliest fixture involving the club was in 1893 but by the end of the decade it had established itself as one of the leading junior sides in the Bradford district with a reputation as a feeder club to senior teams. In March, 1906 it had held Widnes to a draw in a cup-tie at Park Avenue. (Photograph of Victoria Rangers below dates from April, 1907. The featured medal below is that of G. Hudson, a member of the victorious Rangers team in the 1907 BCC final.)

In July, 1908 the club engaged the former Bradford FC player, Herbert Ward as a professional but only twelve months later the Victoria Rangers committee decided to convert to soccer. It must be assumed that this decision was driven by financial problems, the consequence of over-ambition and over-commitment (although conversion had originally been discussed in January, 1907 which was a measure of the frustration with the Northern Union). A new club – Northern Rangers – was formed to continue playing rugby and served as a nursery side for Bradford Northern at Birch Lane but the affair demonstrated the poor state of the Northern Union game at grass roots level in the Bradford district. Indeed, by the outbreak of war, surviving teams such as Wyke and Keighley Zingari were competing in the Halifax & District League.(UPDATE: Northern Rangers subsequently revived the Victoria Rangers identity. Sadly in August, 2017 the club announced its intention to disband on account of being unable to recruit new players thereby bringing to an end a long history.)

Representatives of the Bradford & District Union claimed in December, 1907 that rugby had raised ‘just short of £2,000’ for charity, an amount that seems overstated given that a total of £1,116 was reported to have been raised prior to 1894. In the final six contests it is doubtful that the total net proceeds could have exceeded £300 which would suggest that the aggregate was most likely ‘just short of £1,500’. The quantum was more significant in the rivalry of soccer and rugby and it allowed rugbyites to portray their sport in a positive light, an emotive issue given the ‘Great Betrayal’. (The Bradford CA & FC had previously enjoyed the reflected glory of this funding raising achievement which it claimed was facilitated by its investment in the Park Avenue ground that was also used for athletics events, the nominal purpose of which was to raised monies for charity.)

| Bradford Charity Cup Finalists – Northern Union |

|

|

| Year |

Winners |

Runners-up |

| 1903/04 |

Pudsey Clarence |

Shipley Victoria |

| 1904/05 |

Victoria Rangers |

Shipley Victoria |

| 1905/06 |

Bradford FC ‘A’ |

Buttershaw |

| 1906/07 |

Victoria Rangers |

Saville Green |

NB winners of the Bradford Charity Cup after 1907 (albeit for a different trophy) were as follows: 1907/08: Girlington r/u Stanningley; 1908/09: Stanningley r/u Victoria Rangers; 1909/10: Northern Rangers r/u Rastrick

A Bradford charity cup for cricket

Before rugby football, Bradford had been known for its cricket prowess. The ‘old club’, Bradford CC had been formed in 1836 and by the 1860s there was a thriving and competitive network of local clubs. In 1903 came the formation of the Bradford Cricket League and the following year, the launch of the Priestley Charity Cup which is still contested by members of the league. What it had in common with the Bradford Charity Cup was that it was introduced with the patronage of a serving mayor, William Priestley (knighted in 1909). The Cup was placed under the control of the Bradford Cricket League and in the event of the competition becoming defunct, it was stipulated that the trophy should be deposited in the Cartwright Memorial Hall.

The Priestley Cup should be credited for its part in the success of the Bradford Cricket League and it demonstrated how a prestige cup contest could reinforce and sustain public interest in the rivalry of the constituent clubs. The Priestley Cup is now the longest surviving cup competition for sports clubs in the area and the inheritor of the tradition of the original Bradford Charity Cup. Another factor it had in common was the fact that finals were showcased at Park Avenue, the premier sports ground in the district.

In all probability, the launch of the Priestley Charity Cup (and associated Priestley Shield for reserve teams) was inspired by the Bradford Charity Cup and the desire to have something similar for cricket. Its introduction around the same time as efforts were being made to revive the rugby contest is surely no coincidence. What the two cup competitions had in common was the benefit of each having a prestigious trophy and institutionalised appeal. Of course both shared the virtuous goal of charitable support and the cricket administrators may have been motivated to outperform their winter counterparts with how much money they could raise.In competition with rugby football, cricket proved the winner. Ultimately the success and longevity of the Priestley Cup, which fed off league rivalries, is testament to the fact that cricket enjoyed a critical mass of clubs in the Bradford district of a similar – but sufficiently high – standard to sustain the sort of competitive environment that was not possible after the collective disappearance of local rugby clubs at the end of the nineteenth century. The Priestley Cup thus realised the potential of a local cup competition in a way that was denied to the Bradford Charity Cup.

By 1912 the Bradford Cricket League was consistently donating £100 each year to charity. Evidence of the popularity of the Priestley Cup was demonstrated by semi-final crowds of five thousand at Eccleshill and three thousand at Lidget Green in August, 1913 that generated aggregate receipts of £105. The final that month, between Bradford CC and Great Horton brought a crowd of ten thousand to Park Avenue and gate receipts in excess of £100 which was reported to be a new record for a club game in Bradford cricket. All told, a net donation of £115 was made to the Bradford Hospital Fund in 1913 and in the same year the Priestley Shield was introduced as a charity cup competition for Bradford Cricket League reserve teams.

The Priestley Cup ultimately survived by accommodating the financial needs of its entrants but this was at the expense of charity fund raising. In November, 1917 for example it was claimed that none of the clubs could afford the ‘self-sacrifice’ of participation. Accordingly, changes were made to the arrangements by which gate proceeds were divided between charity, the clubs and the Bradford Cricket League. The original concept of a charity cup competition to raise proceeds exclusively for charity was therefore limited as much by the ability of entrants to forsake gate receipts as the appeal of the competition to the public – whilst noble in its aims, by the twentieth century the economics of sport conspired against the success of a cup competition to be a successful form of charity fund raising. The symbolism of giving to charity was thus always more significant than the giving itself.

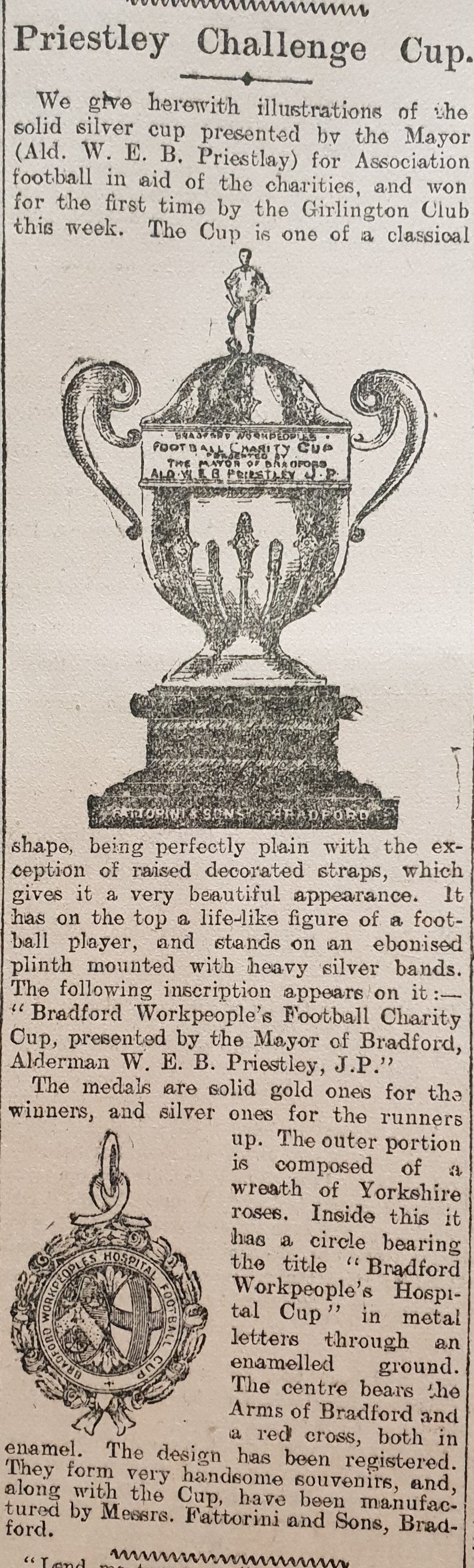

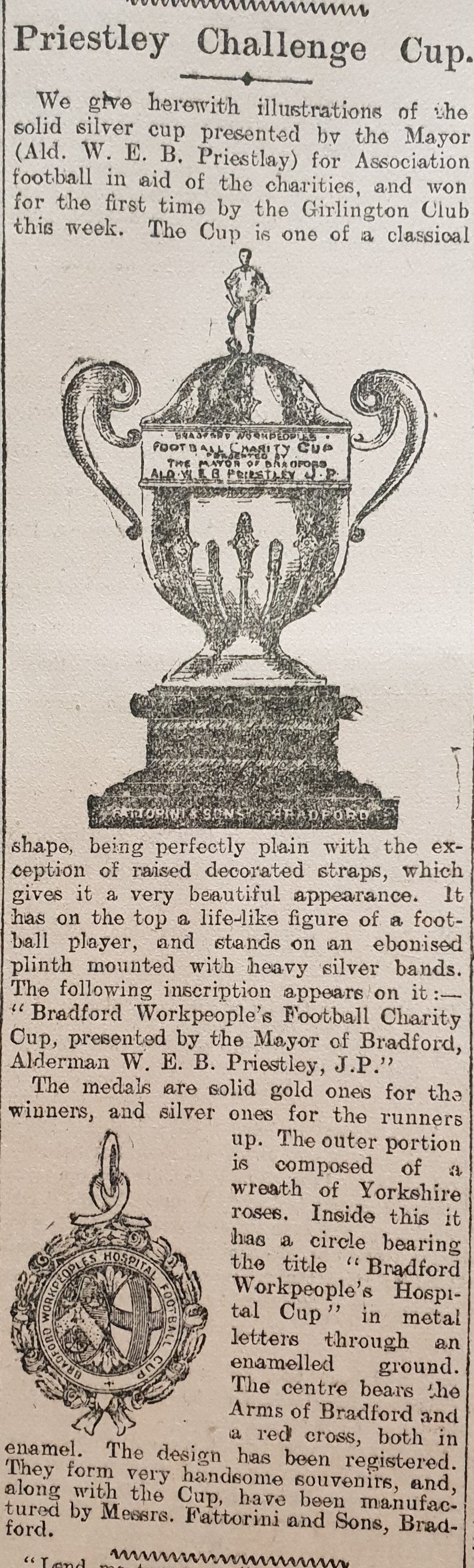

The Bradford Charity Cup becomes a soccer trophy

As far as soccer is concerned, Bradford has never had the same number of junior sides of a reasonable standard to replicate what had existed with Bradford rugby in the boom years between 1884-1897. For that matter soccer lacked the strength in depth of Bradford League cricket despite the grass roots popularity of the sport. In 1903, the Bradford & District Football Association launched its own charity cup competition for local sides (known as the Bradford Junior Charity Cup or Bradford Hospital Cup) but it was a relatively low profile affair. Alderman Priestley donated another trophy for this competition in 1904 (as illustrated below).

Meanwhile the original Bradford Charity Cup remained in the possession of Bradford FC but was not used. In 1910 came a unique initiative to bring it back to life with the adoption of the trophy for soccer. The background to this were the attempts to launch a semi-professional Yorkshire league and the efforts in particular of John Brunt and Charles Marsden, leading members of the Bradford & District FA. (Brunt had been behind the launch of Bradford City in 1903 whilst Marsden had been a founder member of the club and latterly a committee member.)

There were two objectives behind the initiative. The first was missionary, to promote the development of association football in West Yorkshire. The second was to find a practical solution of the problem faced by Bradford City AFC (as well as Leeds City) in the identification and nurturing of local youth talent through a reserve team / junior competition. Subsequent to formation the Bradford City club had discovered that the West Yorkshire League was inadequate for its needs whilst the cost of travel had made membership of either the Midland Counties or North-Eastern leagues prohibitively expensive.

Discussions had been initiated in December, 1908, the timing of which is notable given that Bradford City had just secured membership of Division One after promotion the previous season. To make a Yorkshire League a viable proposition required the leading south Yorkshire clubs to defect from the Midland League. In turn it forced the likes of Sheffield United and Barnsley to evaluate their own priorities – proselytising for the cause of soccer and leaping into the unknown through membership of a new league or sticking with their existing arrangements and maintaining loyalty to the Midland. Their choice proved to be the latter, presumably on economic grounds. However memories of the previous decade had not been forgotten and there would have been little enthusiasm to repeat the experience of the aborted Yorkshire League that had lasted only two seasons, 1897/98 and 1898/99. (The ill-fated competition had originally included the reserve teams of Sheffield United, The Wednesday, Doncaster Rovers, Mexborough, Barnsley St Peters and then Sheffield FC. With the collapse of West Yorkshire sides who had proved to be weak opposition, the South Yorkshire clubs had resigned to form the South Yorkshire League and the Yorkshire League collapsed. Further detail is told in my book, Life at the Top.)

The Sheffield Daily Independent of 28 December, 1908 reported that ‘There is little disposition among the clubs of this part of the county to throw over the interesting and well-managed Midland League in order to add more missionary work to that which they have already accomplished. Certainly in Sheffield itself there is none.’ The reluctance of the Sheffield clubs to get involved required a change of format and the promoters were forced to look north of Bradford / Leeds instead of south.Eventually, in 1910 came the launch of the Yorkshire Combination League with a reach beyond West Yorkshire to incorporate clubs in what is now North Yorkshire. It was a strategic venture, intended to strengthen the game in the region. The late development of such a league was a legacy of the fact that West Yorkshire had traditionally been a rugby stronghold and the same factor was responsible for a lack of strength in depth among its soccer clubs. Alongside the two Bradford clubs, the eight other founders of the league included up and coming sides such as Goole Town, Heckmondwike, Knaresborough, Mirfield United, Morley and Starbeck alongside future Football League members Scarborough and York City.

By 1908 Bradford Park Avenue AFC had been elected to the Football League. Eager to derive goodwill, the Bradford Charity Cup trophy was made available for a new competition that was intended once more to generate funds for the Bradford Infirmary. By endorsing its use, the Park Avenue club was able to position itself as a patron of sport and charity once again. It was a convenient arrangement and Brunt and Marsden seized upon the opportunity to utilise such a prestige trophy to compensate for the fact that the Yorkshire Combination might be dismissed as a lesser competition. There was also symbolism in adopting the Bradford Charity Cup for a new high profile county-wide soccer competition as if to demonstrate that association football and not rugby was the dominant sport. Sponsorship of the revived Bradford Charity Cup by the Bradford Daily Argus also reveals an eye to marketing and hints at the ambition of the promoters.In February, 1911 the Bradford Charity Cup committee was able to boast that the association game had raised a total of £1,095 for charities in eight years compared to £1,940 in nineteen years of rugby. It is impossible to validate the accuracy of the claim and both figures were probably overstated – the soccer contribution was presumably generated by the ‘Junior Charity Cup’ that had run since 1904 given that this sum could not have come from the revived (senior) tournament in 1910/11 alone (which was reported to have not been particularly successful in terms of monies raised). Nonetheless it provides an illustration of how the competing football codes gauged their status according to charitable giving.A cup competition was regarded as a vital ingredient to raise interest in the new Yorkshire Combination League and its members. It also provided a degree of equality for all clubs who otherwise competed in different county or local charity cup contests. The members of the league were therefore invited to compete in a new cup competition and the Bradford Charity Cup was provided as its showpiece trophy. To make up sixteen competitors with two rounds prior to the semi-finals, the invitation was extended to others. The competition was intended to raise money for charity and became variously known as the Bradford Charity Cup / Bradford Hospital Cup – with the beneficiary being the Bradford Workpeople’s Hospital Fund – despite the fact that it embraced clubs far beyond the Bradford district. (By contrast, the Junior Charity Cup was open only to clubs within a twelve mile radius of the Town Hall.)

It spoke volumes about the stature of Bradford soccer and the prestige of the trophy that the new competition attracted entrants and in 1911/12 a newly formed club by the name of ‘Leeds United’ participated. Even so, only eleven clubs entered the Bradford Charity Cup in 1910/11 which was won by Bradford (PA) AFC who defeated Mirfield United in the final. (Photo shows Park Avenue full back, Sam Blackham with the trophy.) In so doing, it meant that the rugby club, Bradford FC and its successor had each been triumphant – the first instance perhaps of the same trophy being awarded to the same organisation in two different football codes.

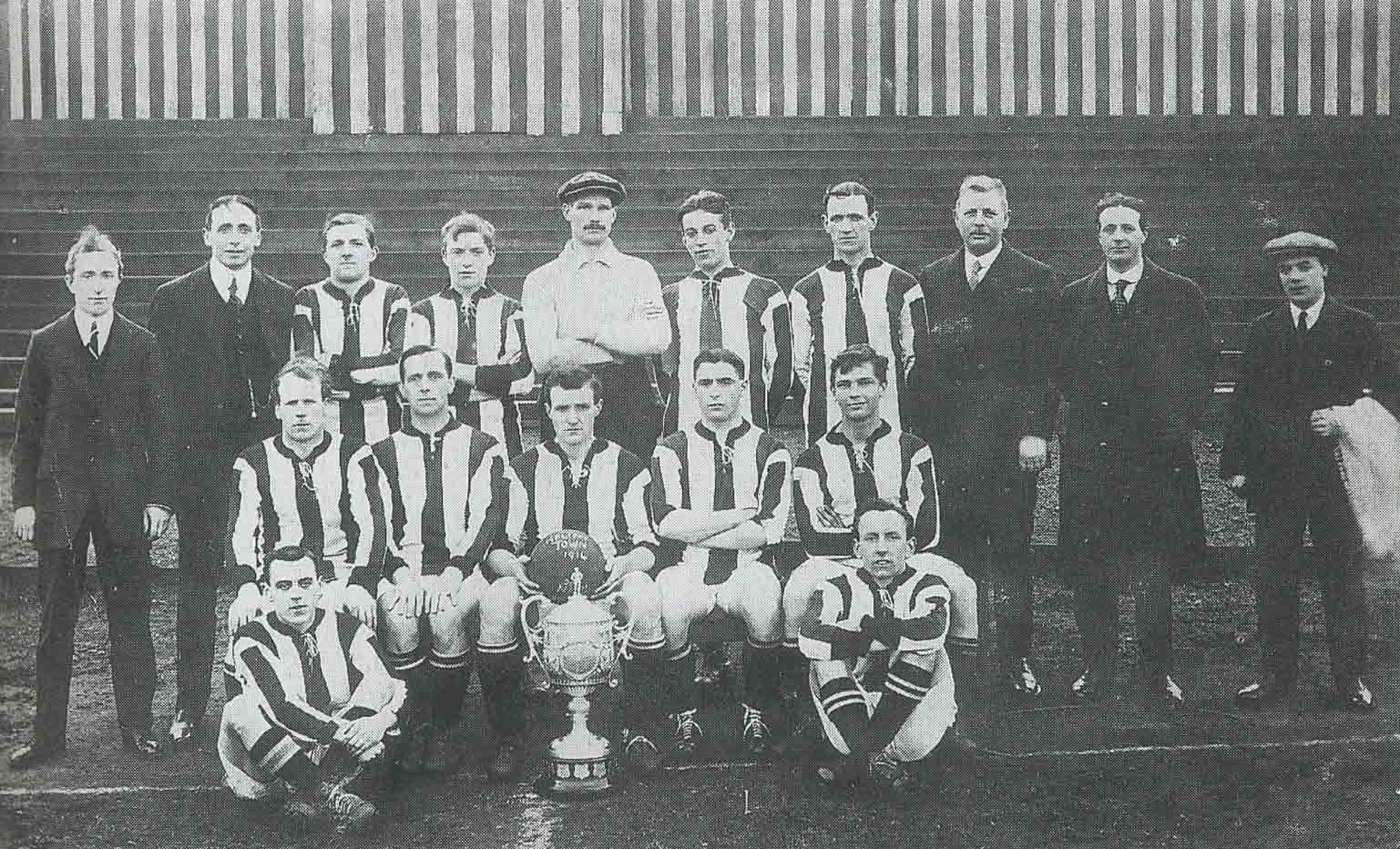

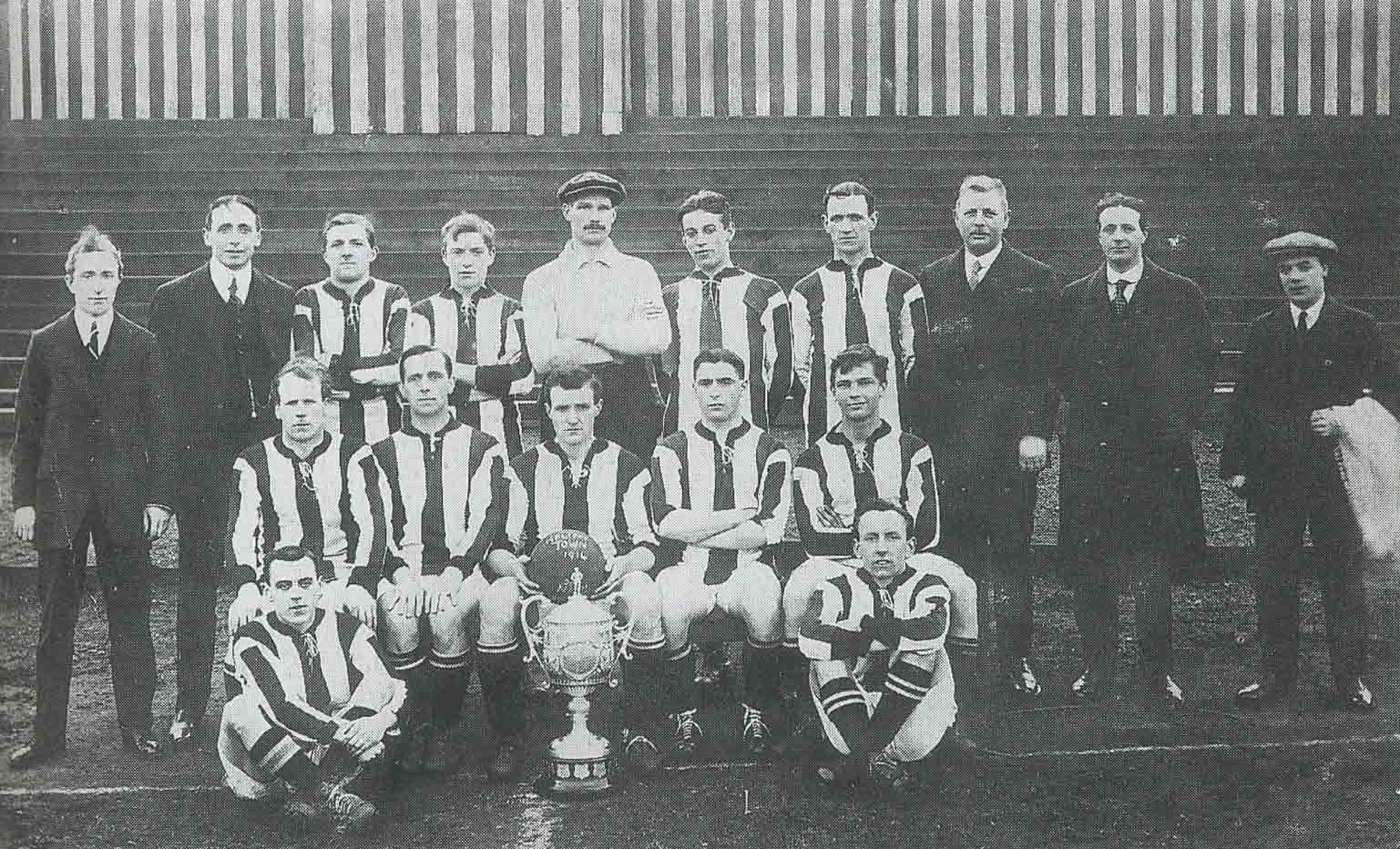

Bradford City AFC similarly emulated Manningham FC with victory in 1911/12 (defeating Mirfield United 4-1 at Sandhall Lane, Halifax) and then in 1912/13 (defeating Morley 6-0 at Valley Parade). The final contest was in April, 1914 when Halifax Town beat Scarborough in the final tie at the ground of York City (who happened to be one of the defeated semi-finalists, the other being Heckmondwike who alone of the four semi-finalists never secured Football League status).

| Bradford Charity Cup Finalists – Association Football |

|

|

| Year |

Winners |

Runners-up |

| 1911 |

Bradford (PA) AFC Reserves |

Mirfield United |

| 1912 |

Bradford City AFC Reserves |

Mirfield United |

| 1913 |

Bradford City AFC Reserves |

Morley |

| 1914 |

Halifax Town |

Scarborough |

It was no coincidence that the Bradford Charity Cup was won by clubs outside the Yorkshire Combination during the final two seasons of the competition. The winners in 1913 were Bradford City, members of the Central League and in 1914 the cup was won by Halifax Town (pictured below with the trophy) who had resigned from the Yorkshire Combination at the end of the previous season to join the Midland League. Ultimately the short duration of the final chapter of the Bradford Charity Cup was due to the weakness of the Yorkshire Combination League. Bradford City AFC for example had remained members of the league for only two seasons and joined the Central League in 1912/13. (The Central League had been launched the previous season, 1911/12.)

Although the Yorkshire Combination had been increased to 14 members by 1911/12, with no disrespect to the likes of Fryston Colliery FC and Thornhill Lees Albion FC, it proved unable to attract quality sides and the Valley Parade reserves had little difficulty winning the championship in both seasons of membership. By April, 1913 it was being reported that the league suffered from the problem of fixtures having to be regularly rearranged, presumably on account of smaller sides struggling to stage a game.

Nonetheless the league allowed players in junior clubs to come to the attention of the seniors, possibly the best example of which was Donald Bell who signed for Bradford (PA) in October, 1912. Six months before he had been a member of the losing Mirfield United team in the final of the Bradford Charity Cup against Bradford City reserves. Bell subsequently achieved fame as the only English professional footballer to be awarded the Victoria Cross for his bravery in the Somme in 1916 where he was killed.

At the end of the 1912/13 season the Yorkshire Combination suffered a further loss in members, among them Huddersfield Town reserves who had been champions in the only season they competed. Surprisingly perhaps, Bradford (PA) AFC remained as members until the end of the competition in 1914 (when they finished as champions) and this may have had something to do with financial constraints that limited the option of joining another league. (Finally, in 1914/15 the Park Avenue reserves enrolled in the Midland League.)

The Yorkshire Combination League was disbanded in the summer of 1914 and the Bradford Charity Cup was similarly discontinued, in all likelihood because it had failed in its singular purpose of raising funds for charity and had lost its catchment. Crucially, in 1913/14 the cup competition had failed to attract quality entrants. Even in 1910/11, the first season of its revival, it was reported that the proceeds had been disappointing. The loss, or rather the absence, of a constituency of decent sides to create a contest capable of attracting public interest made the Bradford Charity Cup a non-commercial proposition. Furthermore it had also found itself competing with other cup competitions. Most reserves teams or junior soccer clubs of that era entered a number of cup contests in a season; it was simply unrealistic to expect that the Bradford Charity Cup could command the emotional loyalty of sides outside the Bradford district in relation to other emergent charity cup competitions.

Besides, it was inevitable that Bradford’s football influence in the region would eventually wane with the emergence of other centres. In 1910 for example, Bradford was the only place in West or North Yorkshire with two senior soccer clubs, let alone one of them a Division One member and in 1911 an FA Cup winner. Indeed, at the beginning of 1910, Bradford City AFC had even topped the first division. Yet whereas in 1914/15 there were two Division One clubs in Bradford, within ten years Huddersfield Town – and to a lesser extent Leeds United – became the leading sides and Bradford soccer was left behind in the doldrums.

A trophy for three different codes

It is remarkable that the same trophy was adopted for sporting competition by three different football codes – Rugby Union, Northern Union and Association. During the twenty years it was competed for, the apportionment between those codes had been ten, six and four seasons respectively. The cup had been brought back to Valley Parade and Park Avenue on four occasions each, under Rugby Union rules twice by Manningham FC, under the auspices of the Northern Union three times by Bradford FC and then as a soccer competition twice by Bradford City AFC and once by Bradford (PA) AFC.

Equally remarkable is the influence of the Bradford Charity Cup for its role as a stimulant of sport and, in its earliest format, the encouragement of local sporting rivalries. It was thus a precursor to the impact of the Bradford & District Football League after 1899 and the Bradford Cricket League from 1903 – two competitions which inherited much the same passion of local, intra-district sporting rivalry. Quite literally, any history of the origins of modern sport in Bradford cannot be told without giving recognition to the significance of the Bradford Charity Cup.

Modern variants

As in 1902, the launch of the Bradford Championship in 1961 was intended to fill the vacuum in the fixture lists of Bradford City and Bradford (PA) to provide the public with a derby game. It was intended to satisfy the blood feud of the declining band of partisan supporters who continued to attend games at Valley Parade and Park Avenue. The fact that the competition was introduced said more about the financial desperation and reliance upon derby fixtures to boost attendances. Meanwhile the concept of a sporting competition to raise funds for charity had long since been forgotten. The Bradford Championship was contested during the three seasons, 1961/62 to 1963/64 inclusive, the period in which the two clubs found themselves in different divisions following the relegation of City from Division Three and the promotion of Avenue from Division Four in 1960. The relegation of Bradford (PA) in 1963 after only two seasons in Division Three meant that the Bradford Championship duplicated League derbies in 1963/64.

After aggregate crowds of thirteen thousand in the opening season, two years later they amounted to no more than eight thousand which was not a convincing public endorsement. Combined with the fact that the clubs were drawn together in the League Cup at Park Avenue in September, 1963 there was a saturation of derby matches in the final season. With the renewal of league derbies, it made little sense to continue the competition and hence it was abandoned.

In 1994, the introduction of The Tom Banks trophy – a pre-season fixture between City and Bradford Park Avenue – is best described as a nostalgia fixture. On all but one occasion the contest has been staged at the home of Bradford Park Avenue yet whilst that club has tended to field first team players, the Bradford City side has typically comprised reserves and triallists which is a measure of the gulf in status between Bradford’s sole surviving League club and the reformed Bradford Park Avenue.

The historic memory

The Bradford Charity Cup is consigned to history, a phenomenon unique to its age. The link between sport and charity fund-raising was ultimately destroyed by the emergence of the Welfare State but the historic significance of the connection was actually far greater in terms of its symbolism than financial contribution. The association with charity served to mobilise interest in athleticism but the experience in Bradford demonstrates that sport, rather the town’s infirmary, gained the most.Even by 1885, Bradford football clubs were not best placed to be vehicles for charity fund raising. As I highlighted in my book Room at the Top, the leadership of The Bradford Cricket, Athletic & Football Club was becoming pre-occupied with the redevelopment and financing of its Park Avenue enclosure. Manningham FC and junior clubs had equally precarious finances even if the amounts involved were not as great. As clubs wrestled with repayment of debt and ground expenditure there was little to be handed to charity. Cynics of that era could rightly argue that the best way to assist the town’s infirmary would have been through direct donation. A cartoon in The Yorkshireman from 18 April, 1885 betrays an element of sarcasm about the full extent of charitable spirit with sellers of ‘charity pies’ and ‘charity oranges’ as well as a busker shown to be taking advantage of the crowd attending the final at Park Avenue.

There remained an enduring link between charity fund-raising and sporting activity and there were various initiatives to raise funds for the city’s hospitals, the following from April, 1919.

An editorial in The Yorkshire Sports of 23 August, 1947 reflected that ‘One of the least happy effects of the new Health Bill which brings all the hospital services under national control, is the severance or sport from that great, endeavour to help finances of what were voluntary institutions hitherto. In that respect Bradford has set an illustrious example, through the medium of the many and varied sporting organisations, of enthusiastic effort to raise money for charitable objects. Virtually every branch of sport through special competitions has played a noble part in subscribing handsomely to hospitals, etc., with the Bradford Cricket League setting the pace through the Priestley Cup competition, which, since its inception in 1904, has contributed no less than £12,500. Football tennis, bowls, and billiards have been similarly devoted to the charitable cause, the inspiration of which has reacted most beneficially on sport itself in providing a strong competitive urge which has appealed greatly to both players and public. One can only wonder what is to happen now to the numerous special competitions with their cups and other trophies. Surely they will not be allowed to go out of existence. If for nothing else but sporting tradition they should be kept going and, with the consent of those in whom the trophies are vested, the funds diverted to other forms of charity.’

Although the Priestley Cup continues in existence, the Bradford Charity Cup is lost to memory and the whereabouts of the trophy is, to my knowledge, unknown. Yet even if the Bradford Charity Cup competition in its different permutations never emulated the financial contribution of the original Glasgow Charity Cup contest, it still deserves to be remembered for its impact on the development of Bradford sport and football culture. At Park Avenue it also fed into the high and mighty, supercilious outlook of the Bradford club by which it had become known in the second half of the 1880s.

However quaint it may seem nowadays, there is no denying that it must have been an incredible spectacle to witness the victorious Shipley FC team returning home with the cup from Park Avenue on Easter Monday in April, 1890 in an open top horse drawn waggonette. The reception from a holiday crowd enjoying a day at Shipley Glen. The Saltaire Brass Band with its rendition of the anthem ‘See the Conquering Hero Come’ – the Victorian equivalent of Tina Turner’s ‘You’re Simply the Best’ or Queen’s ‘We are the Champions’. The moment of fame, celebrated by a generation, a fond memory when in 1901 the club’s ground opposite the Ring Of Bells was sold for housing development.

By John Dewhirst

Discover more about the history of professional football in Bradford in ROOM AT THE TOP and LIFE AT THE TOP by John Dewhirst (Bantamspast, 2016). Details from the following link about these books and other volumes in the BANTAMSPAST HISTORY REVISITED SERIES

.Other online articles about Bradford sport by the same authorJohn contributes to the Bradford City match day programme and his features are also published on his blog Wool City Rivals You can also find book reviews and archive images on his blog.

===============================================================